by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

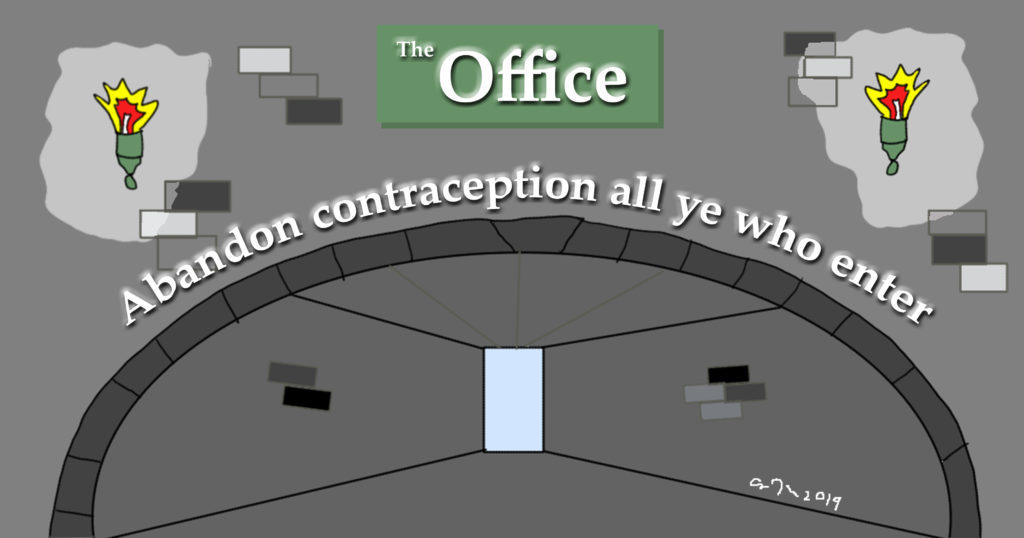

One of the changes that the Trump administration tried to make to the Affordable Care Act was to eliminate the requirementthat employer insurance plans cover the full cost of contraception. The new rules would have allowed businesses and nonprofits a religious and moral exemption from providing such coverage beginning this past Monday. Under the Obama administration, the Courts carved out exemptions for businesses that were religious in nature or that were privately run by a family of faith (see Little Sisters v. Burwelland Burwell v. Hobby Lobby). These efforts continued attempts under claims of religious libertythat people and companies should not be compelled to act in ways their religious and philosophical belief held was immoral—such as providing contraception and abortion.

This week, a U.S. District judge placed a nationwide blockon the Trump rules. On Sunday, a federal judge had blockedthe rules for 13 states (California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia and Washington) and Washington DC.

Most critics of the rules describe concerns that the rules required the Department of Health and Human Services to overreach its authority to give exemptions, a power that is limited in the ACA. Other critics express fears that the rules were an attempt to raisereligious freedominto a categorical imperative overriding all other values and rights. A third criticism holds that the rules are part of an effort to roll back the rights of womento make their own choices, especially in regards to reproductive matters.

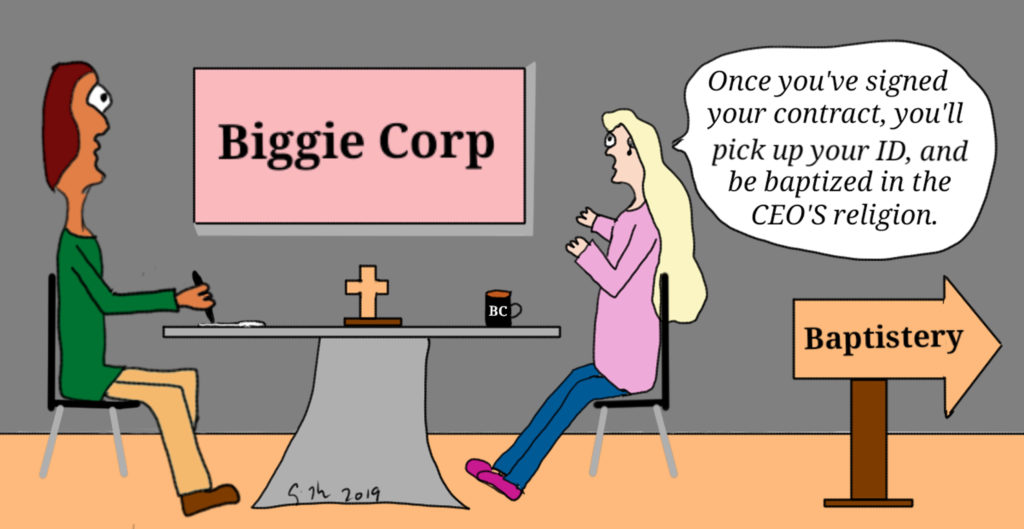

While the Trump rules may be all of these things, my interest is whether such rules are an attempt to privilege the morality of the wealthy above everyone else. Are these rules an attempt of the owners to impose their views of morality on the workers? Being able to practice one’s morality may be related to one’s socioeconomic station.

Historically, all of the subjects of a kingdom had to practice the religion of their monarch. When Henry VIII formed a new church, he also sparked a religious civil war that spanned centuries. In the modern age, the Trump rules explicitly state that owners have a greater right to the exercise of morality than those who work for them. In many ways, this has always been true. Growing up Jewish, I had long been used to the fact that my Christian friends could easily celebrate their holidays since school was closed on those days. For myself and my Hindu and Muslim friends, we had to take a sick day to celebrate our holy days. In fact, when I was very young, the school would give mandatory tests on the Jewish holidays and not let us make them up.

As a faculty member at a religious (not my faith) institution, I am encouraged to take time off to celebrate my religious celebrations. But since the school is open, taking those days means that I need to arrange for a sub, independent learning, or simply cancel classes (giving me less time to teach material in an already cramped 10-week term). Although many of my colleagues do cancel classes to celebrate their holidays, I have never felt comfortable doing that.

A cosmetic surgeon colleague at a religious hospital regularly performed sex transition surgeries for patients desiring that procedure. When the hospital was sold to a new (but also religious) system, she was informed that she could no longer do such surgeries at their institution. Instead, she would have to find another hospital, be credentialed there, and bring “those patients” to another place, which would cost the patients more. Her professional autonomy was curtailed because of a change in policy brought on by a change in ownership—owners who exercised their view of morality no matter its effect on others. In another example, obstetricians in Catholic hospitals have been known to report on an emergency that required performing a tubal ligation on a desperate mother of 5 during her latest C-section. She wants the surgery; the surgeon is willing to do it; but the owners say no since it violates their morality.

In these circumstances, the ruling class (owners, wealthy, the state) had the power to follow their religion and moral ideals, but those who work for them lack that freedom. Research studies demonstrate that moral reasoning is tied to socioeconomic status. A 2013 study foundthat those in the wealthier classes have less empathy and tend toward a more utilitarian method of reasoning: The greatest profit for me.

Such thinking has been discussed often in relations to the lack of ethics in business. When the head emphasizes the bottom line, turns a blind eye, or forces their way of looking on others, then the employees will follow even if it violates their own morality. The Milgram experiment showed that most people will go along with an authority even if asked to do something they know to be wrong. The employee is in the same position, nudged to follow the boss’s morality.

Some might argue that if one disagrees with the morality of the bosses, then one simply should leave and work elsewhere. The ability to just quit and find another, equivalent, job elsewhere is a privilege that most people do not have. The longer one stays in a position, the more benefits (and seniority) are accrued and those are often lost when one starts over elsewhere. Finances, family and other obligations may prevent a person from being able to pick up and move to another city where their moral beliefs are more commonly held. Other people might suggest that one starts their own business if they want to be the one who sets the moral tone for their work. As a teacher, I can hardly just open my own university. Also, as an independent contractor or small business owner, a person does not necessarily get to set the morality of their business, but rather has to follow that of their [wealthier and more powerful] clients. If the clients want a project and require one to work on Eid Al-Fitr, then that is what the small business owner has to do, or risk their livelihood. The higher someone is on the socioeconomic ladder, the more they get to practice their morality and to force that morality on others.

As bioethicists, when we study health care providers and their use of ethics services, or whistleblowing behavior, it is worth asking whether they feel they are free to act against their employer’s morality? I suggest that an unexamined area of structural injustice in the U.S. is that the ability to practice one’s morality is directly related to one’s socioeconomic status and being an owner. For the vast majority of us, our ability to act on our morality can be limited and like the kings of olde, we are often forced to practice our employer’s morality rather than live on our own terms.