by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

An article has sent shockwaves through the bioethics and end-of-life care worlds: A 78-year-old man who was unable to breathe makes his way to the hospital where he is informed in the middle of the night via a telemedicine robot that “he would likely die within days.” The physician appeared on a tablet -like screen attached to a mobile unit and delivers the bad news. An Associated Press article has been published in multiple news outlets with the article headline, “Man learns he’s dying from doctor on robot video at California hospital”. The title has been reproduced in most news outlets, but a tagline has differed: NBC wrote, “The man’s granddaughter said she was stunned to hear from a doctor on a video screen that her grandfather didn’t have long to live.” The Denver Postsaid, ““It should be done by a human.” California man learns he’s dying from doctor on robot video”. The New York Timespublished, “Doctor on Video Screen Told a Man He Was Near Death, Leaving Relatives Aghast“.

In general, response has been negative, especially from the man’s family, who believe it was inappropriate to use a telemedicine robot to delivery news of a terminal illness.

Using technology to deliver bad news is not new. While giving bad news is generally best done in person, it has been and continues to be (with patient’s permission) done over the phone. A recent study of 437 cancer patients found that 18% had been told of their cancer diagnosis over the phone. Sometimes telemedicine is the only option: Consider astronauts on a space station orbiting the Earth. For those in space where a doctor is notpresent, telemedicine is the only way for them to learn about a bad health condition. Jerri Nielsen was the physician in Antarctica when she determined that she had breast cancer—discussing the news and verifying the diagnosis had to take place via telemedicinebecause during the long dark summer there, personnel and goods can only be moved with great difficulty and at high risk (her chemotherapy was delivered in a drop shipment).

The case of the 78-year-old patient begs the question as to what was the real issue in this case: The use of a telemedicine robot? That the telemedicine was used badly? Or that a health care provider gave bad news poorly, irrespective of the method?

In the first question, there may be a generational effect. A senior might react poorly to the impersonal use of a robot while a younger person may not have an issue. A 2010 study of reporting cancer diagnoses found that satisfaction was higher with patients told in person of their diagnosis. The study population had an median age of 53 and 85% of the subjects identified as white. However, millennials (people born from 1981-1997) actually expect greater use of telemedicine in their care. Thus, the acceptance or even appropriateness of using telemedicine for delivering bad news and offering medical care may be generational dependent with younger ones more accepting and even expecting it.

Second, did the use of the telehealth* robot violate a standard of care or a norm of service delivery? Telehealth and telemedicine may not have replaced the doctor’s office visit in many places, but it is an evolving technology that will become a greater part of most people’s health care encounters. This is especially true in rural and resources poor settings where specialists are not easily accessible. Telehealth is also valuable in remote monitoring of patientsand providing quick and easy access to a health care provider (think about needing help in the middle of the night but not thinking you are sick enough for the ED trip). Telemedicine is commonly used in ED settings (20% of all use) and in more than half of all hospitals. Most conversations regarding best practices in telemedicine/health revolvearound being business-ready for such solutions, but in general the best practices for using telemedicine is the same as in any clinical encounter. According to the AMA, there should ideally be a health care professional available when the telemedicine encounter occurs. The AMA further recommends, “Confirming that telehealth/telemedicine services are appropriate for that patient’s individual situation and medical needs”. While I could find few guidelines on using telemedicine to give bad news, the reality is that if giving news in person would be substantially delayed, then telemedicine would be appropriate in the same way that giving news over the phone may be preferable than waiting for a distant office visit.

The third question is whether the telemedicine physician delivered the news properly, irrespective of this being a face-to-face or screen-to-face encounter. According to Kaiser Permanente, the patient’s news delivery via robot came after a long day of conversations with flesh and blood care providers. Likely, the patient had been told of the likelihood of bad news before the robo-doc arrived, but did not recall the conversation. In the best of circumstances, patients only remember half of what their clinician tells them. In the case of a cancer or serious diagnosis, patient’s remember very little after hearing the diagnosis. Studies of UK patients receiving cancer diagnosis shows that 86% of patients cannot recall information they were told after hearing their diagnosis.

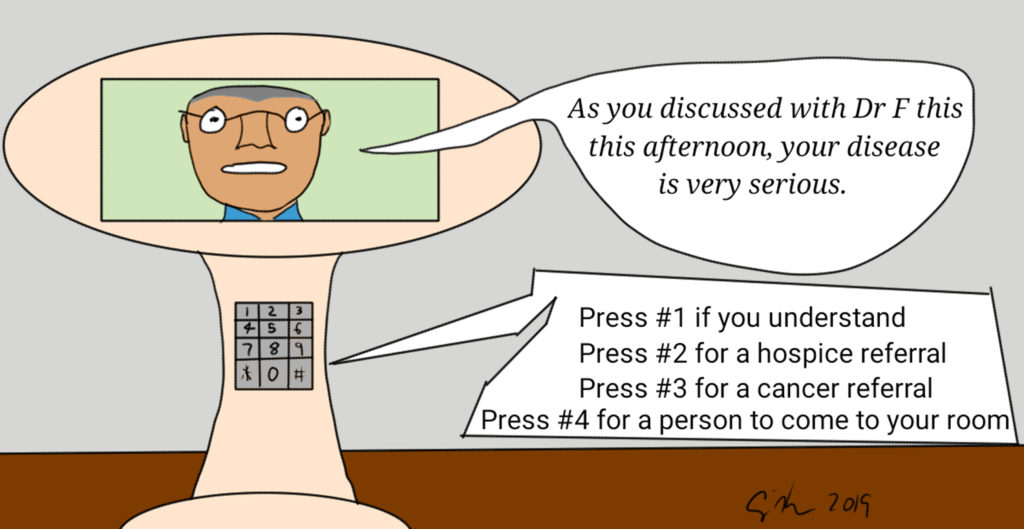

Several protocols exist for how health care providers should go about giving bad news. One of these is the SPIKES framework. First, the care provider should prepare the setting, preferably finding a comfortable, quiet, and private space. The patient should be asked to invite any supporters that they want present. Second, the patient should be asked what do they know and what do they think is going on. This step is known as assessing the perceptionof the situation. Third is to invitethe patient into a conversation by asking how much they want to know and who else should be part of decision-making. Fourth is providing the patient knowledgethat they want about their diagnosis, possible treatment, and prognosis. This step usually begins with a warning shot that bad news is forthcoming (e.g. “The test results concern me” or “The results are not what we hoped”). Fifth, address the patient’s emotionalresponse by acknowledging them. And lastly is devising a strategyfor how to move forward including specific, concrete steps (e.g. “I have made you an appointment on Thursday with a specialist”). Likely, the care provider will have to repeat information multiple times and on multiple visits. In this particular case, the granddaughter claims to have recorded the telemedicine interaction. What she reports is that the patient was hard of hearing and could not hear the robot well (a problem with the technology or best use of it) and that she was shocked when asked if home hospice was the next step and the doctor responded that he did not think the patient would be leaving the hospital.

Just because the use of the telemedicine robot is the new factor in this encounter, does not mean that the family’s dissatisfaction is due to the use of this technology. We have to examine whether the technology was used appropriately and more generally, whether the bad news was given well. It is easy to blame a machine for dehumanizing the patient experience but sometimes people or situations can do that on their own. We also must consider that the family’s grief may have them reaching out for someone or something to blame for the shock of the news and subsequent death. Whereas most guidelines on the use of this technology have focused on the business ROI (return on investment) and broad appeals to professional behavior in its use, it may be time to develop more nuanced guidelines as the use of telemedicine expands.

*For the purposes of this essay, telemedicine and telehealth are used interchangeably.