by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Last week, Amazon announced a new partnership with the UK’s National Health Service(NHS). In this arrangement, when patients ask their Alexa personal digital assistant health questions, the answers will come from the NHS’s website. Instead of scrolling through pages of web results that include some good sources and some not-so-good-sources, people in the UK will find their answers coming from the nation’s health care provider.

The project could be an important step in helping people with access needs. For individuals living with limited mobility, low vision, or who are simply not comfortable with technology, being able to ask for and receive accurate health information with their voice may open a world of knowledge that was harder to access before. For everyone, knowing that a request for medical information will come from a reputable source is better than hoping a random Google search lands on a useful page. The quality of this voice search information means we can rest easier knowing the results have been vetted.

As with most new technologies, the good also comes with some worries. Is this Alexa search any different than a traditional Google search? Is a voice recording any riskier than typing into the NHS website for information? One difference is that in a web search I can choose from a wide variety of source pages (some are good sources and many are not). Thus, my ability to choose my source of information is constrained—health information on Alexa will come from the NHS (at least if I am in the U.K.). In all cases, my search requests and results will be recorded by the company (Alphabet or Amazon). A voice recording is more challenging when it comes to privacy because deep fakes can allow someone to take that voice recording and have my voice say something that I never said. Having a voice print can give someone access to your bank and other accounts, which is why experts suggest never saying “yes” to an automated phone call you receive. A third difference is access to the technology. Whereas, I can access the internet and general searches from my computer, a cell phone, even the library, using Alexa requires that I purchase an Amazon device (the least expensive is $35). This makes access dependent on having disposable income to make the purchase—it also creates a new market for Alexa devices.

Any internet enabled technology brings with it concerns about privacy as well. Although Amazon says it will keep the information “confidential”, it is not clear what that means: They might strip out names and collect people’s data; they may keep the data within its own company (as they claim to plan to do); they might sell information to anyone who pays, or they may not keep any search histories at all (highly unlikely). When you share health information with a physician, there is an expectation of confidentiality because your physician has a fiduciary responsibility to protect you. Neither Alphabet nor Amazon have such a responsibility toward you because you are not their patient (for Alphabet you are a content source) and they do not provide you with medical care. They are data companies who repackage and resell your information. My cynical side says this effort is an attempt by Amazon to play catch up in collecting health information from online searches which they can then market to others. HIPAA and our current privacy regulations were not built for the digital age and companies that provide information without medical treatment. Similarly, while you might believe that your request is kept between you and your device, the reality is that real people will also be listening as part of quality control and employee training, a process that Amazon has recently been called out on.

So, what can happen to the information you provide besides being used for quality control, training, and getting you the information you request? What does Amazon and the NHS do with the search results? In the U.S., it is possible that this data would be useful for insurers, employers, and health agencies to manage risk (i.e. deny you coverage to save money). In some cases, social media and search requests can be indicators of impending disease outbreaks such as the flu. Insurance companies (not so much a U.K. consideration, but a U.S. one) might like to know if a person is suddenly searching for information about cancer or diabetes. Like many online companies, Amazon may be using this information for targeted advertising. For example, you might request information about pregnancy and then find your inbox filled with coupons for baby formula and prenatal vitamins. Amazon is also in talks to develop its own online pharmacy—knowing people’s search terms could certainly help direct people toward purchasing from that service. There is a convenience factor to getting a coupon to treat a disease you have just searched, or to have ordering occur seamlessly. And there is a potential for proactive medicine—your search terms and purchasing history may provide enough information to diagnose a health condition. But the risk is privacy. Many households share Amazon accounts. What happens if a husband has been travelling for months and sees an order for a pregnancy test on Amazon. Or if a child finds out information about their parent that the mother or father would prefer to keep secret. The more sensitive the medical condition and the more integrated information search and ordering become, the higher the risk for people’s privacy to be violated within the family as well as outside it.

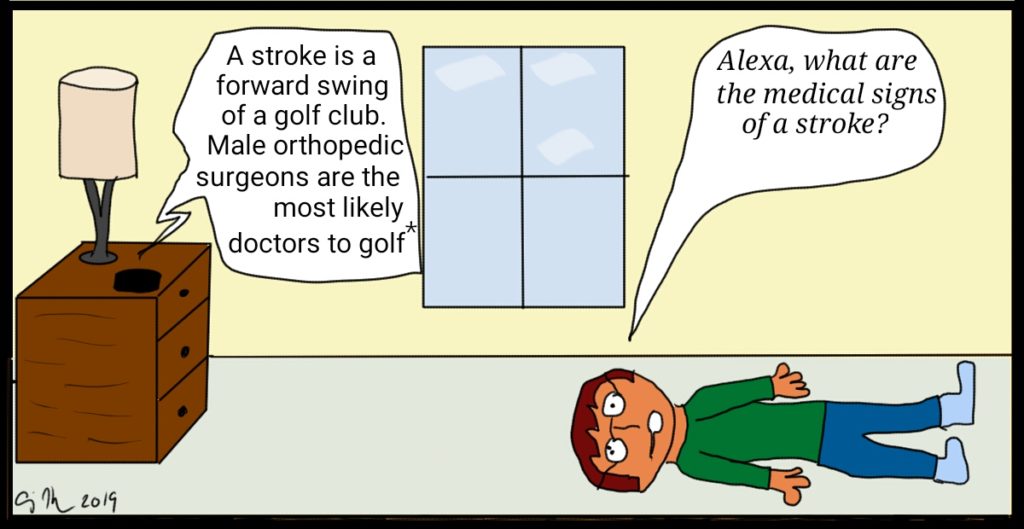

Among the benefits the NHS hopes to see from this partnership is a reduction in the demand to see health care professionals. This statement would suggest they expect people to visit doctors less often. Is Alexa the best medical assistant? One of my concerns is a person who asks Alexa for information, “Alexa, what are the symptoms of a stroke” which the system then gets from the NHS and reads back to you. But what if you are having a stroke? Could the system identify that and call for help? Facebook and other online services have struggled with providing help for people who display suicidal ideationson those platforms. Will Amazon and the NHS have a better solution to get people help when it is really needed? It is also possible that a person can look up a bunch of symptoms to self-treat, but Alexa will not put together that these symptoms are part of a single underlying condition (of course the same is true of my Google search). Or people may be sicker by the time they actually go to a doctor, thinking in earlier stages of illness that they can self-treat. Doesn’t the NHS have an interest in being sure that diagnoses are accurate and useful? It is important that Alexa not only provide information, but suggest when people should talk to their doctors.

Amazon has only announced this program for the U.K. at the moment. If successful, does anyone doubt that the program will spread across the pond? Since there is not a central U.S. medical care system, a U.S. partner would either be the federal government (CDC and NIH) or a private company. Europe is well ahead of the U.S. in creating regulations for the online environment. In the U.S., it is still a wild west. For people with limited vision or mobility, this partnership could literally be a life saver. But for others, there are a lot of unanswered questions for something we have to purchase and may not be in our best interest long term. How much privacy are you willing to give up for convenience?