by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

I recently read Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World written by investigative journalist David Epstein. The crux of the book is that people with more generalized experiences in a variety of different fields tend to do be more successful in their chosen work. The further we range, the better we are.

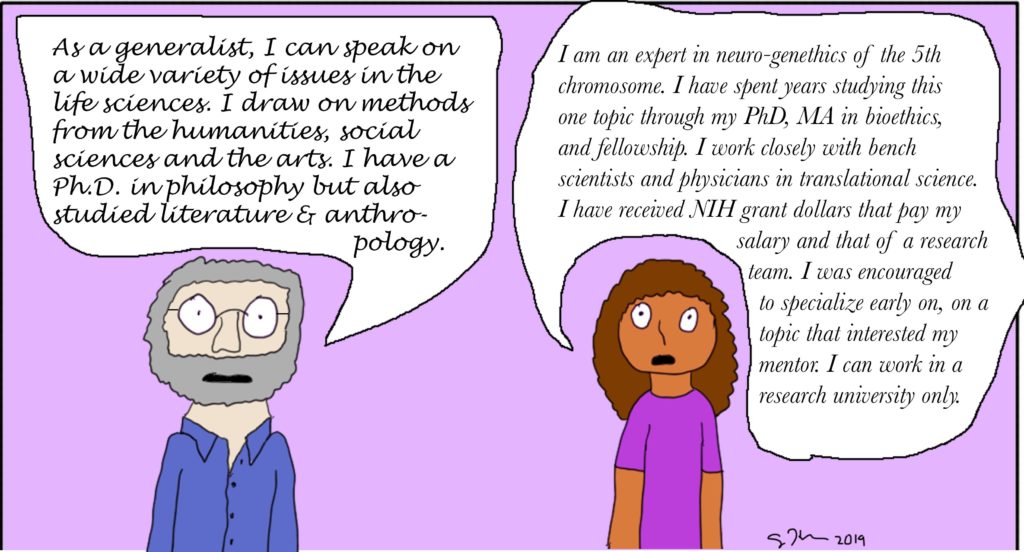

This idea, that broad learning is beneficial is the basis of the liberal arts model—broad exposure to a wide variety of areas and learning with some depth in one discipline. This idea may seem quaint in an era when people are supposed to gain expertise as early as possible in their life and when education programs are being pressured to focus more on job training than well-roundedness. How does the idea of being a generalist, as Epstein describes it, apply to the world of bioethics?

Luckily, this is an experiment that I can do. Back in 2006 and 2007 when my then-state and university were beginning their cuts (Nevada was a leader in the economic downturn that hit others in 2008), I decided to begin applying for a new academic job. I kept a careful listing of all bioethics jobs listed over those two years—127 positions advertised (no, I did not apply for all of them). Ten of them were for fellowships, 18 for assistant professors, 17 for associate professors; 17 for a director of some sort). That averages about 63.5 positions per year. Not all of these positions ended up hiring someone nor were all funded. Some were very specific in what they wanted—a lung transplant surgeon, belonging to a specific religious denomination, a JD, a PhD in Philosophy, MDiv, MD. Many of these were likely written with a ] desired candidate in mind. While a specific disciplinary degree was often sought, the job descriptions were clearly looking for generalists—people with backgrounds in bioethics found through a disciplinary degree. The job descriptions asked for people who could teach, perform research on a variety of topics, and do clinical ethics consultation. Candidates were, for the most part, expected to do it all.

In comparison, I looked at job listings at bioethics.net on September 28, 2019. This included 40 open positions, fewer than 15 years ago. Of those, 16 were for fellows or postdocs; 7 for assistant professors; 2 for associate professor; 3 for clinical ethicists, 3 had the term director in the title, and the rest asked for coordinators, developers and curators. More openings were for non-tenure track or staff postings than for tenure track/tenured ones. A full 21 are for positions that focus on research and 7 were specific for clinical ethics. Seven require a bachelor’s degree and 2 asked for at least a masters. Only 1 specified the type of doctorate (philosophy) whereas all of the others were looking for a doctoral (or terminal) degree in an area associated with bioethics or health humanities. Most of the ads were fairly specific on what the person should study: One ad wanted a person in humanities and bioethics who studies climate change; a few wanted someone who works in translational research; a third wanted specialization in artificial intelligence and big data. We have seen the increase in specializations. At the same time that bioethics positions are more open to people’s backgrounds, the area of study has narrowed considerably. Another difference in this 14-year spread: More of the more recent positions ask people to have a history of external funding.

The results suggest that while we have moved away from requiring people to have doctorates in philosophy or degrees in law, we expect people to be more focused and specialized on what they do. We now differentiate between who does research and who does clinical, when 15 years earlier one was expected to do it all. I suppose that’s because specific areas of research are more fundable, and more fundable if you have a history of funding in that specific area. Also, the development of clinical ethics fellowships and a credentialing process means more time and resources must be spent in pursuit of this expertise as well. Epstein suggests this move might be the wrong direction. For example, the more one is an expert in their field, the less accurate they are in predicting its future direction (location 3312). Epstein cites research which shows the reason a focused expert does so poorly at future predictions is that a deep expert has theories and ideas about how the world works and will fit facts into their narrative. A generalist will take the facts and change their framework.

Given how often we in bioethics are commenting about new technologies and developments in the life sciences (often with Frankenstein’s monster scenarios), this is a genuine concern. We keep saying that germline engineering/stem cell clinics/citizen science/familial DNA searching/big data/artificial intelligence (or pick some other monster technology of the week) may be dangerous and is a threat to our privacy and autonomy that requires the development of ethical and policy guidelines. But our dystopian predictions rarely prove true. Cloning did not destroy the meaning of being human or create a further socioeconomic divide. Three-parent embryos has not led to eugenics. If Epstein’s idea is correct, then if we continue to become more focused on narrower areas, our predictions will become worse. Since a large part of our work is predicting what could happen, if we get bad at this then people will no longer listen.

Generalists are better at contributing to teams and in being team players. They are “high in active open-mindedness. They are also extremely curious, and don’t merely consider contrary ideas, they proactively cross disciplines looking for them” (loc 3421) . I recall studying for my Medical Anthropology MA qualifying exams and seeing analytic tools that were similar to what had been in a literature course as an undergrad and also in some of my reading for my MA in Bioethics. When I brought up this similarity to my professors, I was told that it was ridiculous to think the social sciences could learn from the “soft” analytic techniques of the humanities (this was a big part of why I chose a doctorate in Medical Humanities). Of course, today reaching across disciplines to engage research and analytic techniques is more common (and the basis of my book, Research Methods in Health Humanities).

As bioethics moves toward greater specialization we gain greater access to grant funding and to being part of the medical pantheon where we do our work. Clinical ethicists gain more stature (and maybe salary) as credentialed professionals. But what do we lose? What disappears from the dynamism of bioethics with the passing of the generalist? I often say to students and colleagues that I am fortunate to have come of bioethics age at the end of the generalist era. I appreciate and enjoy that I can do some research, teach classes, conduct clinical consults, and work on policy in a wide variety of areas. I know something about a lot of different bioethics subfields. I regularly draw from literary works and analytic methods to apply to my social science research and I also draw on social science methods to think about my more philosophical ideas. As a generalist, I get to view the bigger picture. However, there are fewer career opportunities for people with a generalist standpoint because we don’t get the big grants, or bill for our consult services.

I believe that bioethics specialization may be practical in our socioeconomic environment, but it comes at a cost to what bioethicists can provide society in terms of developing questions, performing analysis, and making recommendations. It also costs us our own well-being and happiness—generalists tend to be happier according to Epstein’s reporting. While the workplace and economic realities may mandate that we become hyperspecialists in our work, in our education and training programs we must provide a more liberal arts approach where students and trainees learn broadly. “At its core, all hyperspecialization is a well-meaning drive for efficiency…But inefficiency needs cultivating too” (location 4264).