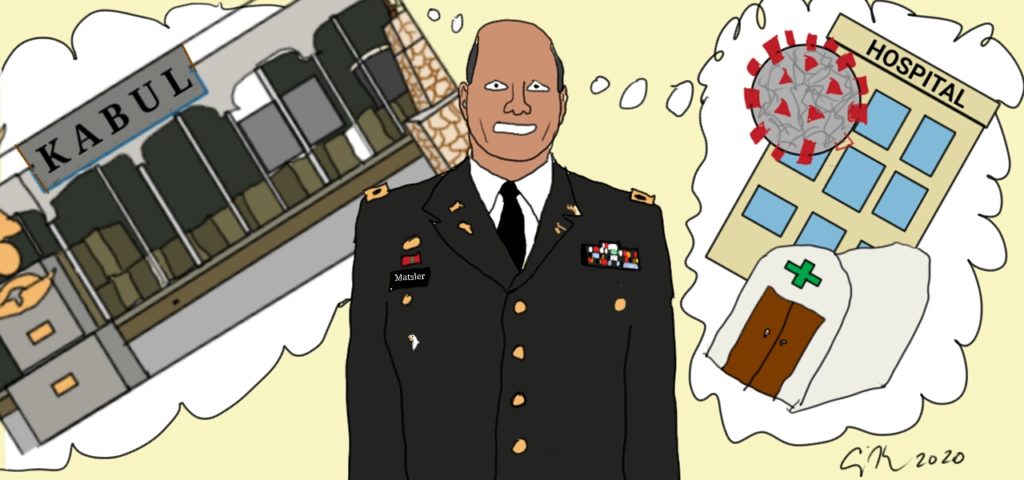

by (Major) Jeff Matsler, S.T.M, Th.M., M.Div.

The moments just before combat begins are as unsettling as combat itself. No matter how hard you’ve trained and prepared for this moment, there’s a fear you’re not ready. You ask yourself, “Can I do this?” “Have I got what it takes to get through the next few moments?” “What if I don’t come back,” or worse yet, “What if I let my teammates and those we’re fighting for down?” The cost of making a mistake in combat is death. You don’t get a redo and there’s no medal for second place when the rule you live by is “Kill or be killed.” Standing on the precipice of battle is enough to make anyone question their ability. But as the shelling starts and chaos descends, as the tanks roll forward, the infantry advance and the bullets fly – in an instant the fear and doubt dissipate, your disciplined training kicks in and you find yourself doing what needs to be done: pushing forward, advancing on the enemy, acting in unison with your comrades as you advance to victory.

I have felt echoes of these emotions as my Ethics team and our healthcare system ramp up for the impending advance and escalation of COVID-19 across the country–and here in Atlanta. As we watch the infection numbers climb day by day, week by week, the anxiety levels rise. We struggle with models of triage and face the reality that in mass casualty events like war and pandemics, not all will walk away – and our guidance to the medical teams providing direct care will in part determine who lives and who dies. We’re not there yet–and I pray we don’t get there. For those who haven’t experienced a MASCAL (mass casualty), whether in a foreign country, the flooded streets of New Orleans or in the rubble of an urban assault, it’s hard to near-impossible to really envision what happens when the rules of order that maintain our society falter. A famous war theorist once said that, “Trying to explain what war is like to the uninitiated is like “a world of virgins studying sex.” As clinical ethicists, on a nationwide level I think that describes what it’s like as we wait for the surge. A pandemic of this magnitude and proportion has not been seen in America during our lifetime and we’re really not sure what to expect. But for me this waiting period does feel familiar. As we draw closer to this great unknown, I recognize these feelings for what they truly are: mental preparation for imminent battle with a ruthless killer that will show no mercy. We must be prepared. And we are.

Right now, most of our hospitals (in the US, at least) still have enough beds and quality of care has not suffered. But as numbers continue to climb toward that critical mass – the point on a chart in some administrator’s office where we officially have more patients than beds and a thoroughly insufficient and steadily declining surplus of supplies– the knot in my stomach gets bigger and tighter. When the balloon goes up, leaders will need our guidance on non-discriminatory models of triage – and assurance that the restrictions on autonomy being imposed – the decisions they make using these models – are not a violation of society’s moral code. They will need us to guide them in their responses when those in harm’s way respond despondently to the restrictions imposed in the name of common health, safety and success in operations.

We don’t have to—and shouldn’t be—recreating the wheel when it comes to our ethical guidance. As a career US Army officer, combat triage and mass casualty scenarios were the standard, not the exception, in training, preparation and execution of ethically appropriate medical care. Disaster ethics already exist. Public health ethicists have already worked through the questions our teams will ask—that part of the work has been done for us. We must be the ones to help providers through this transition in their paradigm of care.

Mass casualty triage models will be uncomfortable—but pandemics and their uncontested consequences are even more uncomfortable. Utilizing and directing supplies and medical personnel in short supply only to those who have a chance of recovery ensures that all who can survive do. If we truly end up in a MASCAL setting, it’s not just going to be uncomfortable – it’s going to be hell. And unless we do all we can to prepare them, our care teams are going to blame themselves for doing what is in reality the greater good.