by Nneka O. Sederstrom, PhD, MPH, MA, FCCP

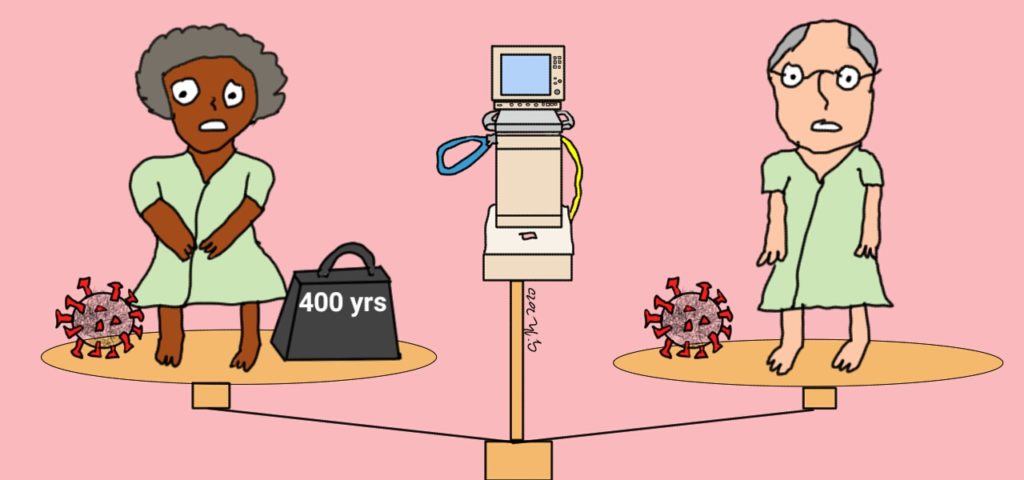

The data are clear: African Americans are becoming infected with the novel coronavirus and dying at a higher rate than White Americans. The rationale is clear: African Americans have higher rates of comorbid conditions than White Americans. The reason is clear: over 400 years of systematic racism, institutional oppression, and continued colorblindness have lead to this outcome. I know that seems like a simplistic explanation for something that is so very complex but it highlights the fundamental flaws we are facing in our guidelines. Clinical experts, from ethicists to bedside physicians, are baffled with what to do to manage this problem. There is a clear recognition that a problem exists, but that is where the thought leaders end. Countless articles and news segments describe the inequity and the reaction of shock. The reality is all news about marginalization and its effects is met with shock. Shock that black women die from childbirth at rates higher than in 3rd world countries. Shocked that black people are denied appropriate medical interventions for cardiac diseases. Shocked that black people, including children, are denied appropriate pain medication. The list is long but yet every time the response is shock. Shock without action is a wasted emotion.For communities of color, trusting an institution that engages in disenfranchisement and marginalization, is a sisyphean task. Crisis standards of care are being debated to include using triage protocols to address inequities. Many have incorporated inequity into their plans through a retrospective review. Well-meaning white people have decided to address the issues of racism, bias, inequities, and disparities is to retrospectively review triage decisions for any noticeable patterns. Let’s put this into context: A hospital lacks ventilators. They activated their triage management and review processes. The triage team, blinded to demographic information, makes a determination based on a generally accepted scoring systems. Later a group of non-triage team members review the decisions, unblinded, for quality assurance and to note any potential inequitable trends. Let’s play it out with patient examples to better understand the process:

- Patients

- Patient A is a 55-year-old African American woman, COVID positive, and history of uncontrolled diabetes.

- Patient B is a 60-year-old White man, COVID positive, and no comorbities.

- Both need the 1 ventilator available.

- The triage team reviews medical facts only and scores accordingly

- Patient B scores better and receives vent.

- Review reveals that 5 of the last 6 ventilator decisions have gone to White patients over African American patients.

- Inequities noted.

Trends will be collated and research will be suggested. These studies will add to the literature and many academics (seasoned and students) will make careers off these writings. As a former doctoral student, I understand the appeal to the research. However, as an African American woman, I am not able to shake the feeling that this is another natural history study with well-meaning White people watching to see the outcome (Tuskegee Experiment throwback for those in the cheap seats). It feels like the medical system is saying to African Americans “I’m not racist, I don’t even see color.”

I often get asked why when someone says “I don’t see color” I respond with “that is a very racist statement and I would urge you to start seeing color.” We all have fallen victim to the colorblind ideology – White people believe that is the only way to “not be racist” and African Americans believe when White people mean they see them as equal. Both are false. Not seeing my color means my most noticeable element is actively being ignored. That blindness is an incapacity to understand that situations affect me differently. My blackness is why I get followed in stores. My blackness is why I get quizzical looks in boardrooms. My blackness is why I hear things like “you speak so well.” The list is infinite and I live with my blackness every day. You don’t see it? Actively ignoring it means you don’t ‘see’ me being followed, or the head tilts in the boardrooms, or understand why a statement about my diction is inappropriate. That willful ignorance is the reason why racism still is a dominant factor in America. Let’s revisit the patient experience, unblinded:

- Patients

- Patient A is a 55-year-old African American woman, COVID positive, and history of uncontrolled diabetes.

- Patient B is a 60-year-old White man, COVID positive, and no comorbities.

- Both need the 1 ventilator available.

- Racially diverse triage team with previous bias training, and a dedicated equity officer, reviews chart to make scoring determinations.

- Triage team request more information regarding uncontrolled diabetes in Patient A.

- Triage team better understands level of impact on Patient A.

- Triage team scores using an equity lens and Patient A gets the ventilator.

- Retrospective review highlights several trends in African Americans with uncontrolled diabetes in a particular area of the city and recommends community outreach.

In the moment equity decisions are new and will undoubtedly cause anxiety. The question to ask is ‘why?’ What about giving the ventilator to the African American woman feels wrong? Is it because using this practice allows for determinations on race and discrimination? Concerns the protocol will not vibe with the ethical framework of ‘most lives saved’? A potential fear of being that person who, even though scored better, still didn’t receive the ventilator? It could be all of these and more. There is no shame in having the thoughts, they just can’t be the only thoughts. Race is already used against African Americans in gaining access to basic rights, why not change the narrative? Is the “most lives saved” standard equitable given the reality of structural racism? It is not and we need to stop acting as if it is. For those who feel the fear of not getting something owed, now you have a small glimpse at what it means to be a person of color in America.

Here is my charge to all: be morally courageous. Defy the seemingly normal urge to watch and wait instead of actively engaging. Be intentional in your discussions and deliberations. Be deliberate in your planning and protocol development. Truly take on the job of addressing inequity in COVID-19. Stop talking about it, just be about it. Be unblinded.