by Nneka Sederstrom, PhD, MPH, MA, FCCP, FCCM

In my previous article, Unblinded, I challenged the actions of using the crisis standards of care scoring systems to allocate scares resources like ventilators and argued against a color-blind ideology. To take that argument further it is time to address the question of “if not that scoring system, then what?”

The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score or SOFA is the clinical tool that has been most widely accepted as the scoring mechanism to address which patient, in a crisis standards of care situation, has the better survival potential if provided the scarce resource.. Although recognized as an imperfect scoring system, SOFA is generally accepted because it is what we have and gives clinicians an opportunity to feel decisions are being made in an unbiased, data driven, utilitarian way. Taking the implicit bias human element out of the scoring provides some sense of fairness in a clearly inequitable system. The problem with this view is that the system is not fair, the tool is biased, and using it will result in continued harm towards populations of color. The scoring system was created from an analysis of predominantly white people with sepsis and septic shock in the ICU setting. SOFA normalizes whiteness as the standard by which all others are measured and is therefore inherently flawed in its discrimination towards populations of color. Although the consensus statement highlights the percentage of participants who are identified as “men” it does not specifically outline any other gender profiles, continuing the bias. So what do we do about it? Is there an acceptable equitable alternative to SOFA? Is there some sort of SOFA+ model that could satisfy the need to feel that decisions are objective and unbiased? The short answer is ‘no’ and the long answer is ‘we know one needs to exist but we haven’t gotten to developing it yet.’ So, what does one do while waiting for science to devise an acceptable alternative that addresses inequities, during a pandemic that is steadily claiming the lives of hundreds of thousands within the United States and with clear disparities in morbidity and mortality? Shrugging our collective shoulders and stating we will work on getting it right for the next pandemic is not the answer nor is it morally acceptable. Action is what is needed.

After all, racism is the soil that has grown all of the systems in America, including the healthcare system. To truly understand how entrenched racism is in medicine, one must look no further than the groundbreaking book Medical Apartheid by Dr. Harriet Washington. In her book, Dr. Washington systematically outlines how the American medical system used the bodies of Black people to advance its knowledge and skills. She highlights atrocities and realities that are imprinted as trauma lived experiences in the descendants of these victims. We cannot begin to discuss improving health disparities without acknowledging the truth of racism in medicine.

Health disparities have always existed and public health scholars have worked hard to outline the disparities in manageable buckets to work on eliminating them. They will not, however, be eliminated because the premise in which programs are being established to address the disparities is not rooted in the fundamental truth that the healthcare system in America is racist.

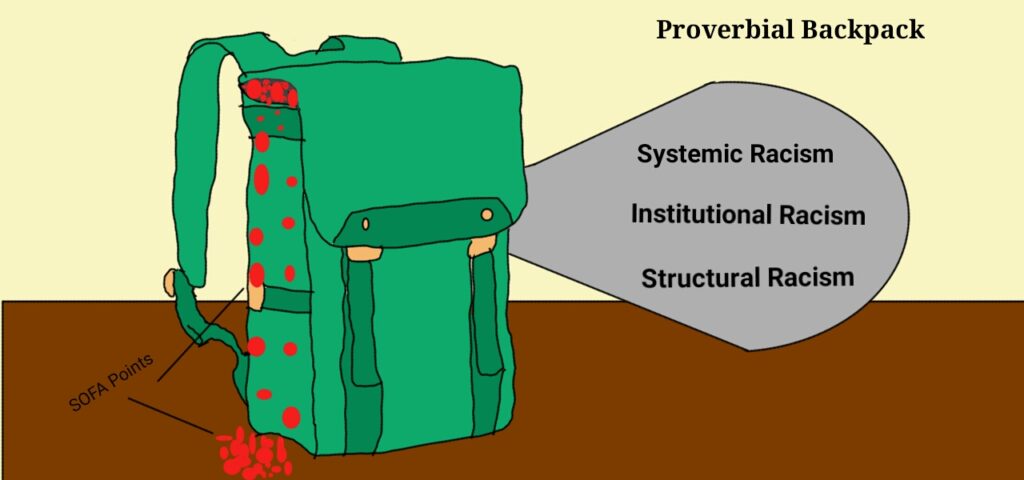

The SOFA system is based on points allocated due to physiological conditions and comorbid states. These points are set to convey a level of clinical infirmity that clinicians can translate into educated guesses on potential outcomes. The more points a patient has, the more likely they are to have a bad outcome. For people of color in America, in particular Black Americans, we are born with points stacked against us. As we grow and the burden of Blackness weighs us down more, our “points” continue to stack up in our proverbial backpacks so they are already brimming with points by the time resource allocations decisions are made in the hospital. In other words, SOFA does not create an even playing field, it perpetuates an uneven one. It is our duty as health care professionals to recognize and respond to this reality for every Black patient. A utilitarian “every patient gets the same tool” approach works when we pretend everyone is starting off at the same level. It is a system that accurately addresses the framework of ‘most lives saved’ when we ignore the backpacks carried on the backs of our Black patients. COVID-19 has ripped open the Pandora’s box of everything we have been aware of, but ignoring, for decades. We can no longer allow for the luxury of ignorance.

Let’s give some points back. I argue that allocating points to counterbalance the additional burden of being Black is not only equitable, it is morally obligatory. The outcome of this sort of ‘give back’ system isn’t to create an environment where this intentional favoritism nets a positive over other patients. It is to intentionally create a net zero starting point where the system can then employ utilitarian approaches in more meaningful ways. Intentionally favoring persons who are specifically disadvantaged due to racism (institutional, structural, and systemic alike) is where the controversy lives. The idea of being deliberate in saying “this person will get this additional (insert whatever privilege one decides like treatment, access, opportunity, etc.) because they are Black or Brown” gives most from White society pause, not because they are fundamentally against it, but because racism in America has trained them to consider this kind of engagement to be flawed – even unconstitutional. I also want to point out that these ‘advantages’ are not true advantages, rather they bring the patient to a level treatment field. If we cannot be deliberate in addressing inequity and racism, then how are we to move forward? It is a false sense of productivity to develop equity and inclusion departments or hire equity and inclusion officers when to truly be equitable and inclusive requires intentional favoring.

Here is an example of what I mean:

Current system:

45-year-old African American man arrives in ED with shortness of breath and clearly in distress. Test comes back positive for COVID-19 and due to the lack of critical care resources at this hospital, the patient must be triaged using the SOFA plus comorbidity scoring system adopted by the hospital for crisis standards of care. The patient’s past medical history shows the comorbidities that make his SOFA score high enough to place him in the ‘red’ category and not a candidate for critical care resources as a result.

Give-back system:

45-year-old African American man arrives in ED with shortness of breath and clearly in distress. Test comes back positive for COVID-19 and due to the lack of critical care resources at this hospital, the patient must be triaged using the SOFA plus comorbidity scoring system adopted by the hospital for crisis standards of care. The patient’s past medical history shows the comorbidities that make his SOFA score high enough to place him in the ‘red’ category and not a candidate for critical care resources as a result. Patient’s score gets adjusted through allocation of two points for being African American/Black/African decent and two points for residing in a socioeconomically disadvantaged community. The point change places him in the green/yellow category which will allow him to have access to resources.

It is time to stop going through the motions in order to appear equitable and actually practice equitably. Developing measurable outcomes to show the shift towards net zero will help health care become antiracist; a path, on which Dr. Ibram X. Kendi has challenged us to begin. What does it mean to be antiracist? Here are Dr. Kendi’s own words describing antiracism:

“The opposite of racist isn’t ‘not racist.’ It is ‘anti-racist.’ What’s the difference? One endorses either the idea of a racial hierarchy as a racist, or racial equality as an anti-racist. One either believes problems are rooted in groups of people, as a racist, or locates the roots of problems in power and policies, as an anti-racist. One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an anti-racist. There is no in-between safe space of ‘not racist.” (Kendi, 2019)

Creating antiracism policies and practices within medicine, specifically to manage crisis standards of care, are mandatory in order to curb the devastation happening to communities of color. Some of us have named our intentions through the statement on racism from the Association of Bioethics Program Directors. Bioethics needs to do more than have a petition, we need to be morally courageous activists, allies to the more invested accomplices who are already working hard to create meaningful change. Helping to change SOFA is one small step.

My charge is radical, but radical disruption is needed. Give back points. Give back acknowledgments. Give back the long deprivation of dignity and respect of persons. Be intentional. Be courageous. Be antiracist.