by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Burn-out is a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by three dimensions: feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and reduced professional efficacy. – WHO, ICD 11

For the last six months, faculty have been under extraordinary pressure. In my own case, we were given 48 hours to transition to online finals to end one quarter and then had 10 days to move from planned in-person classes to completely on-line versions (a.k.a. remote learning) to begin the next quarter. Every few weeks the university asked us to make accommodations for students who were experiencing stress as a result of moving home and having their worlds turned upside down. As a bioethicist with a background in pandemic and crisis planning, my colleagues asked me to be part of the university’s COVID response task force.

Then police officers killing George Floyd in Minneapolis leading to protests and political divisiveness. At a campus that is known for its social justice mission and for a diverse student population, our students became involved and many found themselves experiencing trauma as their communities and homes were in distress. Some were re-traumatized because of their own experiences of having family members killed by police, or being treated as lesser by law enforcement, and living in an unjust society for decades. The university again asked faculty to pivot and relax the last two weeks of spring quarter.

At the same time, my colleagues had to learn about 9 new teaching “modalities” for planning for Fall courses. The task force moved to re-opening issues—how could we safely bring people back to campus (answer: We could not in a dense urban setting). Hours and hours were spent on making decisions about testing, temperature screening, setting up contact tracing, dorms and food service, classrooms, student activities, ventilation systems, music practices, and elevators.

Then, one month from the beginning of fall term, rising positivity rates among 18-29-year-olds in our community and the spread happening on colleges that opened earlier convinced our administration to move the Fall quarter online. Faculty had to switch again from 9 modalities to three, all online.

Thus, we began our new academic year exhausted from the constant pivoting and working to meet student needs. Faculty were also faced with increased service loads and less support. Faculty searches were cut and hiring frozen (some after many months of interviews). Development and travel funds have been swept away. Furloughs, salary cuts, and declining retirement matches were declared. Faculty with children were exhausted from being surrogate elementary and middle school teachers and camp counselors. Vacation is a thing we read about happening in a galaxy far, far away.

All of the effort, time, and expense put into accommodating students was borne on the backs of the faculty. Thus, I was not surprised to see a letter in the Science (August 28th) saying “To be absolutely clear: This. Is. Not. Normal.” The authors suggest that universities realize their faculty are exhausted and stretched and cannot do their regular service and volunteer work. They suggest a triage approach to the normal work of the term. In his mid-August column, Kevin McClure warned academic leaders about the upcoming epidemic of faculty burnout that would arrive with the new academic year.

What about those of us in bioethics? My public health ethics expertise was valuable for my institution and I was happy to be able to help; but it meant a lot of unplanned service work. Plus, I am doing all of this from a table in a hallway in my small Chicago apartment—I haven’t been in the same room with another person for 6 months.

What I outline here is the experience of one bioethics scholar located in a baccalaureate teaching institution. Physicians have experienced increased burnout (1 in 4 report lower well being in the pandemic). Most in bioethics, though, work in medical centers and hospitals. Clinical bioethicists and clinician-bioethicists faced the increased workload of caring for patients that the pandemic wrought. They had had to create allocation plans for shortages of ventilators, ECMO, unilateral DNRs, PPE, medications, and staff. We have all been advising local, state, and federal government efforts. In many large cities, bioethicists have come together to coordinate, write, and respond across instutitions. Many of us have been giving our time and expertise to reporters to help them accurately convey the complexities to the general population.

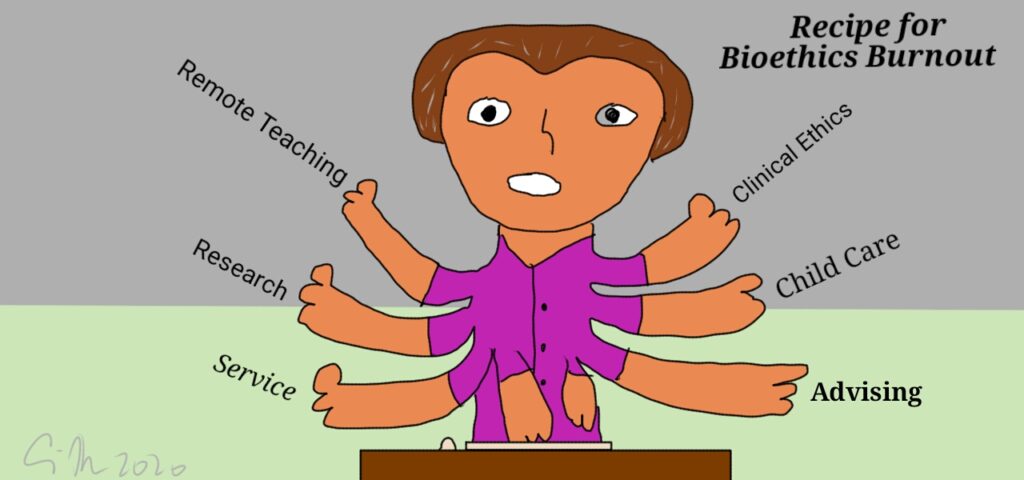

In some ways, bioethics is more important than ever in helping the world deal with these crises. We are writing more, consulting more, and teaching more (how many webinars can there be in a single month?). And we do all of this on top of the teaching, research, and service that everyone else is doing.

Are we about to be hit with a wave of Bioethics Burnout? Are you exhausted? Are you feeling mental distance from your work? Do you have difficulty focusing on work tasks? Do you have negative feelings about your work or seek more mental distance from your work than usual? Are you less effective professionally than usual? Are you unexcited about spending 12 hours a day in front of Zoom for virtual academic conferences? If so, you may suffer from bioethics burnout.

How do we cope and perhaps someday recover? Several friends have suggested taking time for more self-care and just turn off the news: Stop following information about COVID and social injustice. I point out to them that following that news is my job. I can’t teach about public health ethics and provide guidance if I don’t know what is going on.

In one recent conversation, a national group proudly showed me their report on resilience and said that was the answer. My immediate response was that asking people to be self-resilient is not the solution. Over the years, some scholars have suggested that the humanities are the solution to burnout, depression, and rising rates of suicide in medicine. However, reading poetry, writing a journal, meditating, finding a work friend, buckling down are not solutions for this burnout. Reading and knitting, two of my favorite pastimes, have given way to watching hours of Schitts Creek and Star Trek: TNG reruns these days because they take less mental energy. Individual responses are not going to get us through. Expecting individuals to just be strong and keep their chin up is not how we thrive or even survive. Burnout is not a failure of the individual but a failure of the system. These medical and educational systems do not account for human beings and do not have enough flexibility to react to the unexpected.

If the pandemic and civil injustice has shown us anything it is that the system is broken, not the people. A recent post on Inside Higher Ed offers suggestions for institutions to consider to reduce the burden and potential burnout of their faculty including flexible time, deferring tenure clocks, reducing service loads, having more generous leave policies, suspending student evaluations of teaching, and providing childcare options. Other suggestions include providing the tools people need to safely do their work ,from computers faculty can take at home (instead of trying to teach a course on a tablet or cell phone) to making available PPE and sanitizer for people who must be on campus (i.e. campus safety, custodial services). And while it is essential for universities to take care of students, pivoting to protecting their customers (several administrators call the people we educate by this term), that cannot be at the cost of the mental and physical health of faculty and staff.

The bigger answers will require state and federal government to make changes. We need more generous paid leave policies. National health insurance would help people who are burdened by the high costs of care and COVID testing. We need a national response to testing and contact tracing. We need to treat the internet as a utility made available to everyone (about 20% of students had trouble accessing the internet in the first week of classes). We need to have the resources that actually do what the crises and pandemic planning policies recommend. And most importantly, we need science to be leading the response in terms of policy and helping people.

What else do you need to deal with your Bioethics Burnout?