by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

‘We’re out of Options’: Doctors Battle Drug-Resistant Typhoid Outbreak – 13 April 2018

New Concerns Over ‘Super Gonorrhea’ That’s Resistant to All Drugs – 4 April 2018

‘Nightmare’ bacteria, resistant to almost every drug, stalk U.S. hospitals – 3 April 2018

In 1997, I was a new graduate student at the University of Texas Medical Branch, starting my PhD after earning my masters degrees. I presented a paper at the SHHV, AAB, SBC combined meeting in Baltimore on Towards A Communitarian Medicine: Ethics and Responsibility in Anti-Microbial Drug Resistance. I proposed that as a society we needed to address the impending crisis in effective antibiotics by rationing the most powerful, the newest, and the most innovative of these drugs.

Twenty years later, the headlines have caught up with the warning—for strains of some infectious bacteria, we no longer have an effective antibiotic to fight the disease. In 2013, Tom Frieden, director of the CDC announced: “Without urgent action now, more patients will be thrust back to a time before we had effective drugs. We talk about a pre-antibiotic era and an antibiotic era. If we’re not careful, we will soon be in a post antibiotic era. And, in fact, for some patients and some microbes, we are already there.”

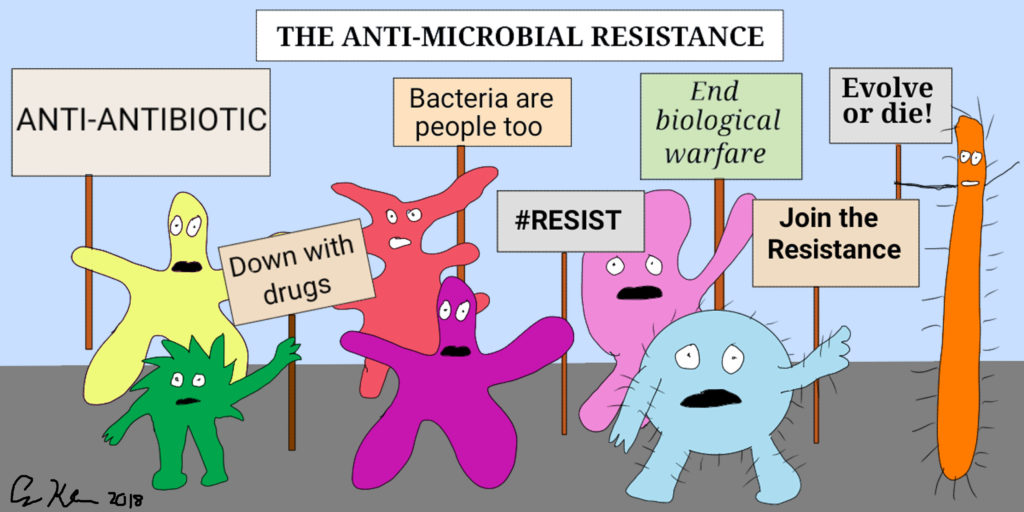

As the headlines that start this piece show, anti-microbial resistance (AMR) is common in typhoid, tuberculosis, gonorrhea, and gram negative bacteria (commonly transmitted in hospital settings). Even Alexander Fleming, credited with discovering penicillin, warned of the developing resistance in a 1945 New York Times interview about his Nobel Prize. I won’t go into the details of antibiotic resistance here, but essentially it is natural selection in action. The widespread use of antibiotics places pressure on the population and favors mutations that are resistant to these compounds. Over time, the frequency of these mutations increases and they succeed in reproducing. The selective pressures come from our use of antibiotics in medicine where 1 out of 3 prescriptions are unnecessary (the person often has a viral, not a bacterial infection), overuse in hospitals (often for preventive purposes; 50% of in-patients are on an antibiotic), and a majority is used in animal husbandry to grow animals that are healthier and bigger (60% of sales of antibiotics for use in food-producing animals are medically important for humans; 70-80% of all antibiotics sold are used in agriculture).

As the headlines that start this piece show, anti-microbial resistance (AMR) is common in typhoid, tuberculosis, gonorrhea, and gram negative bacteria (commonly transmitted in hospital settings). Even Alexander Fleming, credited with discovering penicillin, warned of the developing resistance in a 1945 New York Times interview about his Nobel Prize. I won’t go into the details of antibiotic resistance here, but essentially it is natural selection in action. The widespread use of antibiotics places pressure on the population and favors mutations that are resistant to these compounds. Over time, the frequency of these mutations increases and they succeed in reproducing. The selective pressures come from our use of antibiotics in medicine where 1 out of 3 prescriptions are unnecessary (the person often has a viral, not a bacterial infection), overuse in hospitals (often for preventive purposes; 50% of in-patients are on an antibiotic), and a majority is used in animal husbandry to grow animals that are healthier and bigger (60% of sales of antibiotics for use in food-producing animals are medically important for humans; 70-80% of all antibiotics sold are used in agriculture).

How has the world of bioethics engaged in this antibiotic apocalypse? According to Jasper Littman at the Institute for Experimental Medicine, Christian Albrechts Universität Kiel, “Ethicists have so far largely ignored the issue of AMR.”

Some European and Australian bioethicists have written on the issue and a Brocher Foundation conference was held in 2014 on the topic. In the U.S., AMR has received very little attention. Michael Selgelid at Australia’s Monash University wrote about the causes of resistance being “the over-consumption of antibiotics by the wealthy; and it, ironically, results from the under-consumption of antibiotics, usually by the poor or otherwise marginalized.” Thus, Selgelid views the problem as one of justice—unequal distribution. Both cases, overconsumption and underconsumption can be direct causes of resistance mutations.

Littman, along with his colleagues, suggest four bioethics approaches to examining resistance: (1) restriction of individual liberty (to buy antibiotics on the market) for the communal interest (slowing down the development of resistance); (2) global distributive justice, similar to what Selgelid discussed; (3) the use in veterinary medicine for agriculture as discussed above; and (4) intergenerational justice—do we owe future generations access to effect antibiotics by limiting their use today? In another article, Littman raises questions about the lack of innovative treatments in the development pipeline (who should ensure development, how is it funded, how are they distributed, how should they be tested). He proposes that the use of antibiotics be viewed as stewardship—protecting the efficacy of these compounds—which may mean restricting their use in humans and animals.

One technological solution may be to speed up development of novel agents—new approaches to attacking bacterial invaders. However, there has not been much movement on this front. A 2017 World Health Organization report found that out of 51 antibiotic agents in development, only 8 are potentially innovative approaches. Of course, an approach is not a guarantee of an approved drug. Of these, most are IV drugs needing to be taken in a hospital setting—very few antibiotics for oral use are being developed. If this area is seen as important by our society, then we need to encourage government to make development a higher priority—offering financial incentives to companies, to university labs, and other researchers.

In my 1997 work, I suggested that we view antibiotics not as a market widget to be bought and sold freely, but as a public utility; that is, as a common good that requires a more public health approach. This is the position suggested by Littman and about which I spoke twenty years ago. Among my recommendations were:

- putting new, effective antibiotics on reserve which can only be accessed upon application and approval of a committee that would control access.

- Hospitals could test patient’s infections and those with resistant ones are placed in a separate ward to prevent transmission to others.

- Doctors and patients should be educated to only expect antibiotic prescriptions for bacterial infections and not for viral ones.

- Enhanced tracking of use of antibiotics sales and use should be done at a national and international level. As the US FDA reports in its 2016 study of antibiotic use in animals, much information is confidential and they cannot legally access it. Such protective laws need to give way to this greater public health need.

- The use of antibiotics for non-medical need in animals must be curtailed even though it may mean lower yields and increased food prices

- The use of antibiotics for preventive procedures (such as surgeries, dental care, and even travel) should be curbed (or only used when absolutely necessary).

- Develop guidelines that require delays in prescribing antibiotics to only be after a period when supportive care is tried first. For example, antibiotics are not the first round choice for children’s ear infections anymore.

- Given the justice concerns with high and low income disparities in use and access, approaches need to be global. Bacteria do not recognize political borders so our solutions need to be international.

Such methods prioritize the group (community, society, world) over the individual, similar to many public health ethics frameworks. Several scholars have suggested that such approaches would go around autonomy and raise justice questions of balancing rights of future lives and needs over current ones.

In the U.S. especially, our worship of individualism has often meant resistance to communal perspectives of health decision-making. Littman suggests that bioethicists are needed to work on: “translating agent-centred moral concepts to the population-level and elucidating the relational and socially embedded normative concepts that will underpin the AMR response, such as solidarity, reciprocity, stewardship, collective harm, trust, community, health justice and the common good.”

In the last decades, bioethicists have been part of foundational approaches to crisis planning for pandemics and other potential disasters, helping governments craft preparedness plans. We have written on these topics but we have also engaged in practice. Questions of solidarity, reciprocity, stewardship, justice and common good are part of a developing literature on crisis preparedness, most often found in policy white papers. Thus, we do not need to start from ground zero because much of this work has been done. Public health preparedness and bioethics’ role in it may provide a model for how bioethicists, policymakers, and responders can collaborate in tackling AMR. We ignored the problem for twenty years and it has not gone away. We need to engage now.