by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

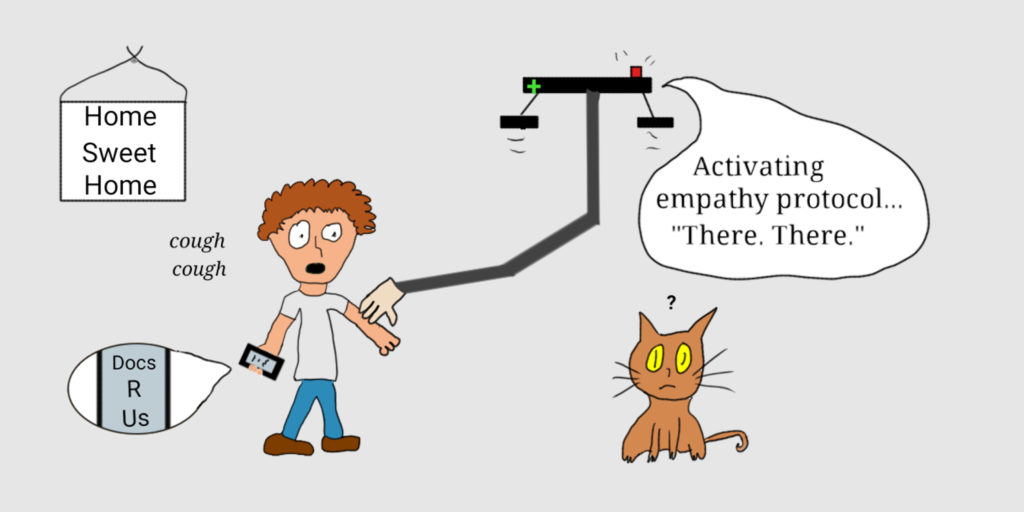

A new medical school opening this fall in the University of Illinois system will focus on the tech revolution. The foundation of the school is technology and engineering and thus is selecting students with backgrounds in math, computers, and data science. They hope to train a new generation of clinicians who will “disrupt” how medicine is practiced. When the dean offered his vision of medicine practiced by the graduates, he described a scenario where patients talk to physicians through cell phones and where drones deliver diagnostic tools and treatments to your door.

I was taken aback when reading this news story in the February 9th issue of the Chicago Tribune.

After all, one of the goals of the humanities in health and medicine is to encourage physicians and patient to engage on the human level, the opposite of this proposal. However, I’m not supposed to worry because humanities will be part of this new curriculum, just not in any way I would recognize: “Humanities will cut through all of the courses, including instruction on how cultural, environmental and religious differences can affect perception of care. One project at the medical school is exploring how art displayed in physician waiting rooms can change patients moods and outcomes.”

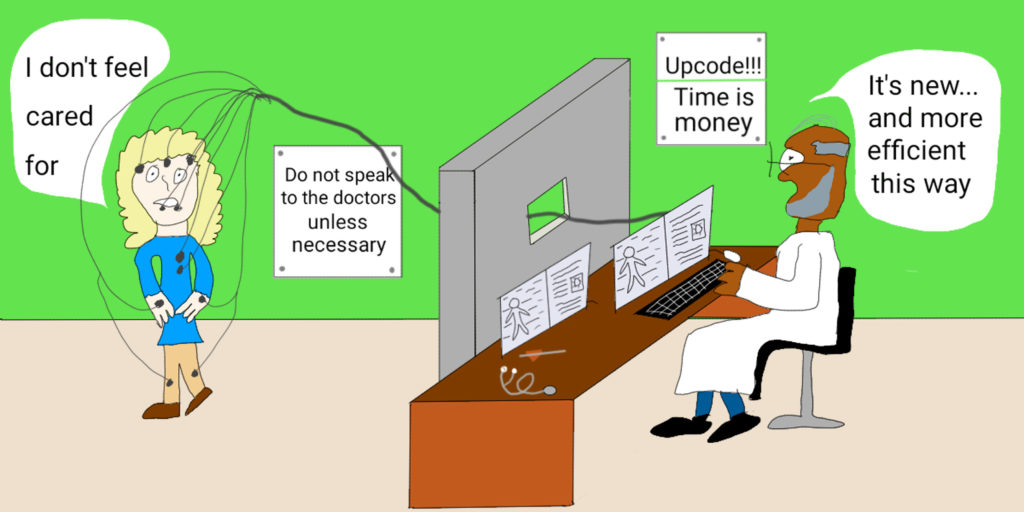

One of the criticisms of how the humanities appear in medical schools is that they are presented only instrumentally—to learn compassion, to learn observation skills, to learn how to talk to another person. This school’s vision demotes the humanities from being instrumental to being merely a clinical skill. This goes back to the now discounted view of cultural and religious competency where people’s core beliefs, values, and worldviews are reduced to “a technical skill for which clinicians can be trained to develop expertise.” The value of art is to use it to manipulate mood? The health humanities are not technical skills but an insight into the human condition.

Here is a medical school that relishes throwing off the old and encouraging clinical distance. In the tech world, old is considered bad, inefficient, and a target for change. Old is 18 months ago. Efficiency and innovation are the most important thing and human-to-human connection is neither efficient nor innovative. “For traditionalists, who value human touch, that scenario may seem undesirable. But Li said it would improve costs and access, especially for people live far away from their doctor; and free up humans for tasks robots can’t do. “The only thing the doctor doesn’t do is put a hand on you and listen to your heart,” Li said. “But those are old techniques.” The stethoscope, he notes, is 200 years old.”

Indeed, the stethoscope was brought to life in 1819 after 3 years of study and experimentation. This was an innovation on the practice of physician’s listening to patient’s chests with their ears, a process that goes back to 1,500 BCE. Innovation and change can be good—the stethoscope was such an improvement on relying on the ear alone that it has become a symbol of the physician. The next goal is to develop a system that doesn’t require a human ear at all but a machine that can more accurately and more precisely identify what is going on beneath the skin. Each step, has the effect, however, of distancing the physician from the patient: Pressing ear to chest was replaced by a tube between ear and chest and now the ear will be removed altogether. The healing touch is being replaced by the electronic embrace.

This technological medicine may have some real benefits—a more intelligent telemedicine. For people in isolated areas, such innovations could provide care that was not available before. In many areas of our lives, technology reduces cost, except in medicine. In the world of health care, technology has the effect of increasing costs. In fact, blame for the rising cost of health care—far beyond the level of inflation—is squarely on the increasing use of technology. The idea of technology transfer in universities is not to invent devices and give them away for free but rather to patent and then license technology to generate money. And you can be sure that the innovations these students create will belong to the universities, not their student-creators.

Can a human physician be replaced by a machine? The answer is, probably. Devices can accurately read physical signs and symptoms with greater accuracy. They can quantify the various processes of the body and identify where one or more have gone awry. Expert computer systems can translate this data into diagnosis and suggest treatment. Other machines can give treatment—robotic surgery (though it currently requires a human operator new systems do not), drug delivery machines, and self-injecting patches. In Japan, robots are providing care for the elderly by tracking their vitals, reminding them to take their pills, suggesting activities to keep them active, and to alleviate loneliness—think of a robotic pet.

What are the tasks that robots cannot do? Even the cuddliest of robots and tech cannot offer the human touch. Perhaps a group of new specialists can be trained to visit patients after the drones leave and just lay an understanding hand on the patient’s arm for a moment. Or maybe the treatment kit includes an internet-connected life-like robotic hand that can perform this function as needed. Yes, the physical connection is part of the effectiveness of the touch. But the healing touch also requires having confidence and trust in someone who has actively listened to your concerns, acknowledged your suffering and worries, and spoken with you as a fellow human being.

You can’t show compassion through an app and you can’t provide comfort through drones. This article reminded me of Abraham Verghese’s efforts to bring back the physical exam: “The old-fashioned touching, looking and listening.” Verghese believes that the exam and human touch are important in building a relationship between patients and physicians as well as to be able to choose more wisely what tests to order. He laments the loss of connection when you only view a patient as a data point.

Old is not bad and should not automatically be thrown out. Frequently, older medications turn out to be more effective and cheaper than the newest prescription. Ironically for someone who works in bioethics, I hate going to the doctor and would probably welcome FDA approved DIY-drone-cell-tele medical care. But what all the shiny steel and silicone in the world will not replace is the comfort, the compassion, and the sense of being cared for that the doctor’s touch provides.