by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Update: The U.S. Court of Appeals in D.C. full panel ordered the government to arrange for Doe to receive her abortion. The administration has not announced whether it will appeal to the Supreme Court. On Wednesday morning, she underwent the abortion.

Jane Doe is a 17-year-old woman who illegally came to the United States from Central America. After learning that she was pregnant, she opted for an abortion. However, the U.S. Federal government is preventing her receiving this medical service. The reason is a combination of Texas law, federal law, and moral politics. She is now 16-weeks pregnant.

Under Texas law, a minor who wishes to have an abortion must have the consent of at least one parent or receive a judicial bypass. Then she must wait at least three days between the request that includes counseling (such as an intra-vaginal ultrasound) and receiving the procedure. Since Doe is alone in this country and feared abuse at home, a judge granted her bypass request and appointed a guardian. Her guardian arranged for private funding for the medical procedure. She had appointments at a clinic on both October 19 and October 20.

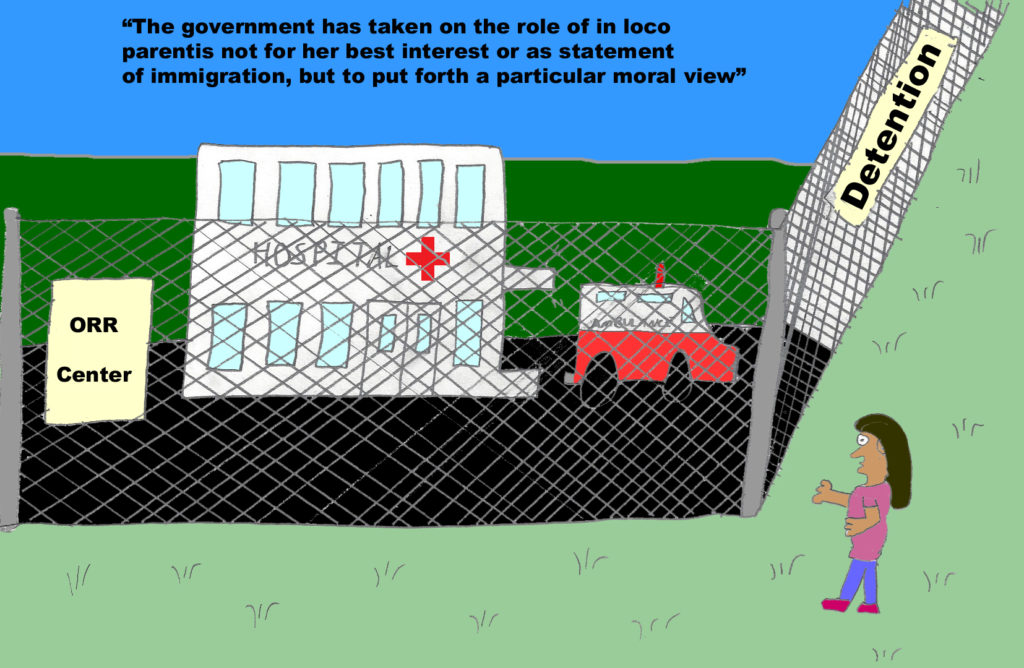

However, the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), which cares for unaccompanied immigrant minors once they enter the U.S., has prohibited her from having access to the abortion. Under a new federal policy, pregnant minors held by the ORR are blocked from having abortions. The policy was instituted by head of the federal refugee agency overseeing the detention centers, E. Scott Lloyd, who was appointed by Trump and is an avowed anti-abortion activist. ORR has instructed the shelter housing Doe not to transport her, nor permit her to be transported to a health care facility for an abortion. Instead, she was taken to a crisis pregnancy center (a religious, anti-abortion institution) for a sonogram and counseling. Officials called her mother in the home country and informed her of the pregnancy. Attorneys for the ORR said that allowing her to access the clinic would make the government “complicit” in the abortion. They further argued that she is free to leave the shelter if she will agree to immediate deportation to her home country. However, no Central American country permits elective abortion. Thus, choosing deportation also ensures that she will not have access to a safe, legal abortion.

On October 18, a DC federal judge ordered the government to permit Doe to have the abortion. That same day, the Justice Department asked the US Court of Appeals in DC to stay that ruling. On December 20, the appeals court ruled (2-to-1) that the government had until the end of October to find a sponsor who could provide housing and ostensibly, allow her to have an abortion. One conservative judge said that this solution prevents answering the larger questions about abortion rights and government authority to prevent someone from obtaining one. A liberal judge on the panel wrote that Doe’s Constitutional rights were being violated. Several willing sponsors have filed applications.

There are several legal questions that this case raises (that are beyond my professional scope to answer):

- Can a federal official and his agency prevent a woman from having a medical procedure that is legal under federal and state law?

- Should a federal official use a regulated government agency to put forth a personal moral vision?

- As an undocumented, unaccompanied minor immigrant, does Doe have the Constitutional right to an abortion granted under U.S. law?

- The U.S. Supreme Court has previously ruled that prisoners have a right to health care provided by the government. Are Doe’s rights being violated or does she not have this right? If she was a US citizen in a US prison, she would indeed have a right to a medical procedure that would have to be provided for her.

- By code, ORR is supposed to provide unaccompanied refugee minors with the same medical care available to U.S.-born children. Why is a different standard being applied in this case?

In addition, there are several ethical concerns raised by this case as well:

By calling her mother, without Doe’s permission to disclose, officials probably violated Doe’s right to medical privacy. Under several laws (including HIPAA, Patient Privacy Act) and under ethics (Hippocratic Oath, AMA Code of Ethics), patients have the right to confidentiality of their medical information. However, given that Doe is a minor, her parents may have a right to her information depending on her geographic location. In 37 states, at least one parent must be told and/or consent to reproductive medical care (specifically, abortion) while in others, a 17-year-old has complete privacy and competency to consent to reproductive-related procedures. In addition, one reason for the judicial bypass was fear of abuse at home: The official’s action in informing her parents may have put Doe in harm’s way.

Under autonomy, Doe has made a clear decision and has been consistent in that desire. As a 17-year-old, she lacks competency to make her own health care decisions. However, in many states, a minor does have the right to make her own reproductive choices, including abortion. Plus, in this particular case, a judge has made a substituted judgment in favor of her wishes. Doe had the unfortunate luck to be detained in Texas. What if Doe had been caught in another state, such as Illinois? Since Illinois does not require parental consent for an abortion, nor a waiting period, nor required counseling with an ultrasound, Doe could have received an abortion more easily. However, if she has been detained by ORR, she could have still been subjected to this catch-22, be prevented from receiving a legal and safe medical procedure in the U.S. or be deported.

In this case, the DHHS and ORR officials are acting as moral captors—preventing Doe from exercising her autonomy. Preventing someone from accessing medical services is a violation of human rights. Yes, she violated law by coming to the country illegally. But she is being denied medical services available to other prisoners and persons. The government has taken on the role of in loco parentis not for her best interest or as a statement on immigration, but to put forth a particular moral view about abortion. This is paternalism at its worst.

Another analysis is to consider the types of rights in this case. The right to an abortion is a reserved, negative right: A party should not get in the way of a person seeking this right when certain conditions are met (in the case of abortion in Texas having parental consent or judicial bypass). However, this may not rise to being a positive right: A party must make the right available. A positive right here would be that the government must provide an abortion just as it must provide Doe with food and shelter. The U.S. does not recognize a positive right to abortion—you can access it but no one has to make it available for you. However, in this specific case, Doe is not asking for the government to provide an abortion or even to provide funding. She is asking them to not block her. That is, they are violating her negative right—to not prevent her, within reason, from receiving medical care. From a philosophical perspective, the turn toward moral paternalism is only defensible if women and judges who grant bypasses are considered less competent than others or if the state has an overriding interest in preventing an abortion sought at 15-16 weeks. Given that Doe has jumped through all of the burdensome hoops Texas has created, the federal government has no ethical legs to stand on at this point. They are restricting her liberty to secure a legal and human right.

The ACLU has filed for a full appeals court review to move the case forward sooner. Since doe is currently 16 weeks pregnant, and under Texas law, an abortion cannot be performed after the 20th week of gestation, time is of the essence.