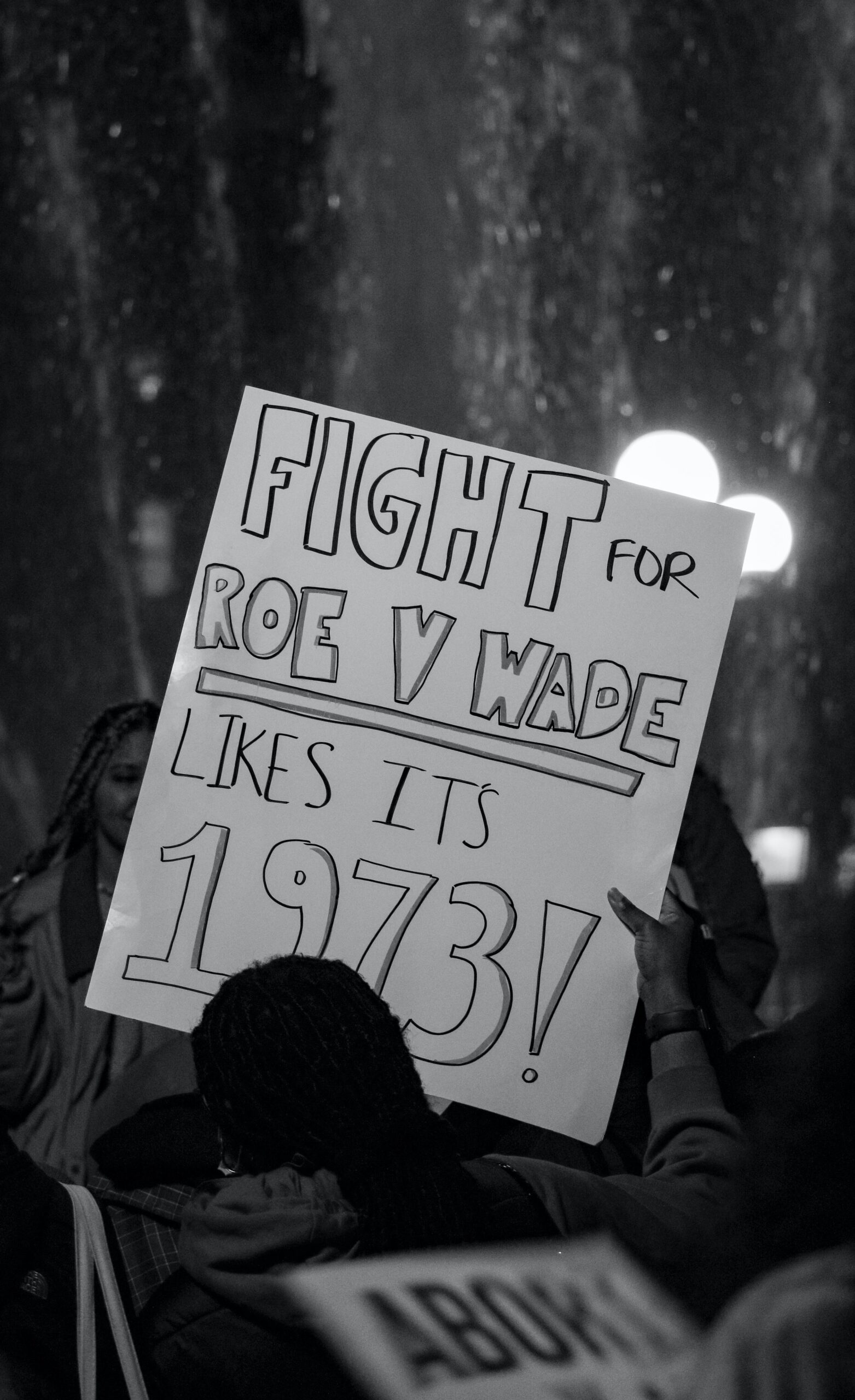

With the new academic year underway, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of abortion scholarship, advocacy, and care. We are feminist bioethicists who, despite having an institutional affiliation at a Catholic university in Missouri, are unequivocal in our support for abortion care. Abortion is not immoral; laws and religious doctrine banning it are. Hours after the Supreme Court released their official statement overturning Roe v. Wade, Missouri was the first state to publicize the enactment of a trigger law that made abortion illegal in the state. As of now, any provider who induces an abortion in the state can be charged with a Class B felony. Missouri is one of 26 states which had similar laws poised to ban access to abortion care upon the release of the Supreme Court’s decision, which precipitated a tide shift for ongoing state-based and national restrictions. Despite overwhelming political and religious narratives which aim to restrict and silence patients and providers, bioethicists and those involved with or affected by our work must be unequivocal that scholarship and advocacy must continue, especially among those of us who find ourselves affiliated with institutions who wrongly believe that abortion is a violation of the inherent value of human life and/or who live in states that do or seek to criminalize abortion.

We will continue to teach abortion scholarship and advocate for abortion access, despite legal infringements which serve to criminalize the safe and common healthcare decision to end a pregnancy. We will do so because these infringements are direct violations of foundational principles in the fields of bioethics and healthcare broadly, and will result in unacceptable and preventable suffering and death. While bioethics should be well-equipped to discuss the ethics of abortion care on the ground, it has failed to do so in at least two ways. First, bioethics tends to engage with the topic of abortion by promoting esoteric debate distant from the lived realities of patients and health care providers, thus failing to live up to its interdisciplinary aims. Second, historically, bioethics scholarship has framed abortion as a debatable health care option, thus negating the fact that abortion is the best medical option in some circumstances and shoud be available as a health care option to anyone for any reason. In entertaining both-siderism, bioethics as a field fails to acknowledge that abortions are health care.

Bioethics emerged as a field in response to ethical questions posed by advances in medical technology, instances of unjust medical experimentation, and the need for a systematic way to think about ethical issues in medical research and practice. As bioethicists, we are trained to navigate disagreement on ethical matters that arise in the context of healthcare, supported by principles developed through sound philosophical inquiry. The overturning of Roe and subsequent state-specific bans codify into law the demands of a small subset of people who hold a particular religious viewpoint, essentially ceding moral ground and granting state power to a select few. Such a ruling is inconsistent with governance in a pluralistic society, and rejects long-established and well-reasoned traditions of prioritizing patient conscience in healthcare decision-making. The fact that a sect of largely white Christian Catholic and Protestant evangelicals have used the power of law to infringe upon the health, and yes even religious, rights of others does not stand in for a generalizable ruling on the morality of abortion. In reality, criminalization of abortion is rooted in classism, white supremacy and misogynist control of bodily autonomy, directly contrary to basic health care ethics principles. If anything, there is now an even stronger moral imperative to protect reproductive health care and access. This moral imperative aligns with at least two of the foundational principles of bioethics–autonomy and justice. Abortion bans violate both.

Autonomy

According to the bioethical principle of autonomy, patients have the right to make decisions about their own health care to the extent that they are able. To respect a patient’s autonomy is to acknowledge that patients are in the best position to know their own goals and desires and to make healthcare decisions accordingly–even if those are not the decisions that others might make. This includes decisions related to pregnancy: whether to continue the pregnancy and parent, continue and choose an adoption plan, or terminate the pregnancy. Limitations on decision-making in sexual and reproductive health care, especially in response to the whims of a vocal religious minority, are unethical violations of patient autonomy. Those limitations that restrict abortion access and selectively make circumstantial exceptions like sexual assault or risk of imminent death are still violations of patient autonomy. Autonomous decision-making through informed consent suggests that a patient’s reason is reason enough, including if their reason is solely because they do not want to be pregnant. There is no ethical autonomous pregnancy choice when it is forced by law, coerced by limited resources or geography, or removed from counseling within the patient-provider relationship.

Justice

Abortion bans further violate the bioethical principle of justice, as new and worsened limitations on healthcare access will disproportionately impact marginalized and oppressed communities. The law simply makes it much more difficult for impoverished pregnant people – who comprise the vast majority of those accessing abortion care – to access the care that they need. Poverty drives both the majority of unintended pregnancies and the majority of decisions to access abortion care, and forced parenthood often further entrenches the pernicious cycle of poverty. From a feminist ethics perspective, centering the needs of those at the margins is central to justice work: in the abortion care context, this means acknowledging those already disenfranchised socially and in healthcare. As such, the targeting of people who can become pregnant is a heartbreaking breach of bioethical justice and serves to harm people with intersecting marginalized identities including sex, gender, race, and class. Poignantly, examining the specifics of abortion ethics justice from a reproductive justice (RJ) framework, defined by SisterSong as the “human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities,” illustrates the ethical intersections of autonomy and justice align in real time. The injustice of abortion bans leading to forced, unconsented pregnancies is further exacerbated by horrific rates of pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality primarily among Black and Native communities, all tragically likely to significantly worsen with limitations on pregnancy options.

Furthermore, criminalizing abortion means weaponizing the work of healthcare providers. Reproductive health specialities overwhelmingly condemn the decision to overturn Roe, and fear the implications bans will have on their daily practice. We know based on high quality national evidence that abortion care is safe, but laws limiting its access or infringing on provider scope or practice make it much less safe. Many laws now instruct providers to cross an ethical and legal boundary of privacy to report patients’ diagnoses and outcomes, which we have already seen happen in Texas. Such breaches have prompted the US Department of Health & Human Services to renew emphasis on confidentiality for sexual and reproductive heatlh care including abortion. The possibility of reporting mandates is a frightening addition to nonsense abortion laws already in place that require providers in some states to force patients to undergo waiting periods, pelvic exams, ultrasounds, and counseling, all of which are known to be directly contrary to evidence-based care. Finally, criminalizing abortion care denies healthcare workers the ability to provide comprehensive, evidence-based, and individualized care for their patients. It is a denial of the conscience to provide that many healthcare providers hold true for ethical abortion care, rights, and access.

To be sure

Many of us who find ourselves working for or studying in conservative religious institutions are told that we need to keep quiet about our firm support of abortion access and reproductive justice, or that abortion access is an inappropriate topic of discussion, or that we need to change our positions outright. We are told that we knew what we were signing up for when we joined such an institution. To be sure, we often have some idea of the politics of the institutions where we work and study. But the notion that we can all choose where to live, work, and study based on alignment with an institution’s moral and political identities (or a state’s moral and political identities for that matter) reflects a misunderstanding of economic, political, and geographic reality for many. Analogously, as conservative institutions, including conservative religious institutions, purchase more and more hospitals, patient care decisions are governed not by patients and their providers, and not by sound medical practice, but by the political views of hospital owners, churches, and other conservative institutions–even if those decisions are harmful to patients. The trigger laws exacerbate and expand this phenomenon, essentially punishing people for where they live by restricting access. But these laws will not keep the body politic, nor its scholars and advocates, quiet.

We know firsthand the pressure that institutions can levy against their members to selectively engage with real-world topics. As an intellectual/academic topic, the conversations we have in classrooms are far removed from people’s lived experiences – we talk about personhood and definitions of life and entirely cordon off pregnant people’s lived reality. Advocating for abortion care access is a bioethical imperative not because it’s a fun puzzle in analytic philosophy, but because people are being actively harmed as we speak. Statements directly from leaders in bioethics are a start, but need to be overt in support of abortion as healthcare to fulfill baseline bioethical principles we describe above.

The overturning of Roe brings with it the force of law to pressure silence and complacency. Quite simply, sometimes people need abortions, and denying them access to that care is a matter of suffering and death on a massive scale. So, as feminist bioethicists, we plan to continue pushing for reproductive justice in our thinking, teaching, and advocacy and encourage all of our academic communities to do the same. The rights of patients, and the principles of bioethics, implore us to.

The views expressed in this essay represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their employers or the Catholic church.

Stephanie Tillman (she/her), CNM is a PhD student at Saint Louis University Department of Health Care Ethics (@FeministMidwife).

Yolonda Wilson (she/her), PhD is an Associate Professor at Saint Louis University Department of Health Care Ethics (@ProfYolonda).

Lou Vinarcsik (she/they) is a MD/PhD student at Saint Louis University Department of Health Care Ethics.