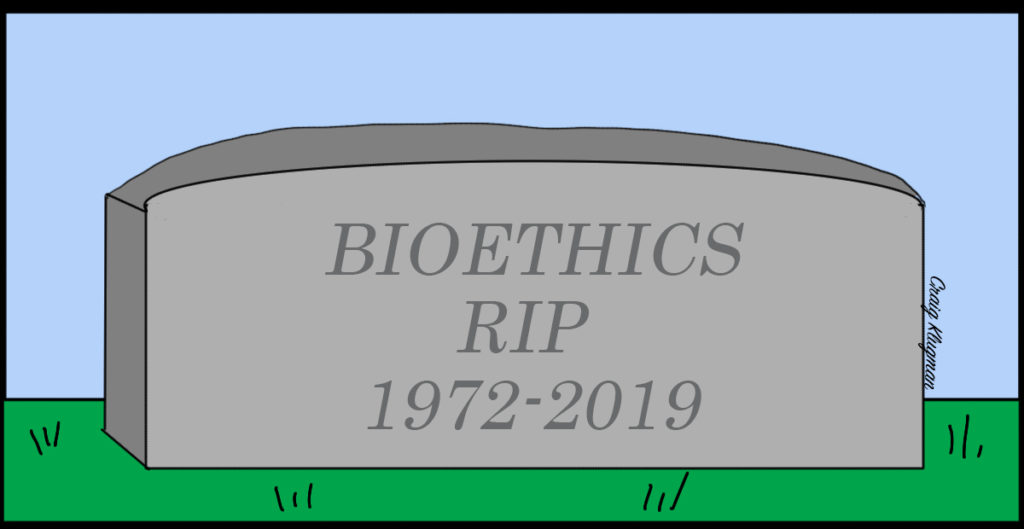

by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

A commentary in Nature this past week suggested that bioethics may no longer be relevant. The author argues that the pace of technological change is so fast that bioethics can’t keep up: “Bioethics, once a beacon of principled pathways to policy, is increasingly lost, like Simba, in a sea of thundering wildebeest.” The author is Sarah Franklin, a sociologist and director of the Reproduce Sociology Research Group at the University of Cambridge (UK). Her work has focused on the development of assistive reproductive technology. She holds degrees in Women’s Studies (MA), Anthropology (MA), and Cultural Studies (PhD).

Dr. Franklin links bioethics with regulatory rules and agencies. She offers a detailed history of bioethics which focuses on ELSI funding, writing the Belmont Report, and the National Research Act. She credits bioethics with providing ethical guidance in research until now.

With the dispersion of research around the world as well as the increasing amount of research done by private companies and citizen scientists, she feels that bioethics is no longer “in the room where it happens”. At the same time, she feels bioethics has lost its mooring: Staring in the 1970s with a root in philosophy, she says it became more interdisciplinary and more empirical. Franklin suggests that modern bioethics is about getting the public’s opinion about what science ought to be done while there are “policymakers, polling companies, and government quangos” (an administrative body outside the government but supported by and sanctioned by the government) who are better equipped at engaging the public. To Franklin, bioethics is no longer the decider of what research is ethical or how to do responsible researcher, a role that has been taken on by funding bodies, journal editors, policymakers, and popular polling.

This article shows a common misunderstanding: Bioethics has never been the arbiter of what can be done. Bioethicists have never had the power to say what research can and cannot take place. Her claim that we have fallen out of favor and out of power is based on a mistaken idea that we ever held such lofty positions in the first place. We never have. Sure, we consult, serve on boards, and offer frameworks for understanding, but that is a far cry from being Clotho, Lachesis, and Moirai (The Greek Fates).

Where did Franklin get this idea? The answer may be from conservative bioethicists who believe that bioethics is the champion of a “culture of death” that is destroying modern civilization because it is “secular” and “relative” (i.e. non-deontological Christian). For example, following on Franklin’s article, Wesley J. Smith quickly wrote in The National Review his own interpretation of Franklin’s piece, “Nature: Bioethics is Obsolete”. In Smith’s world, the battle for the soul of bioethics was between Christianity (Ramsey) and a secular relativism (Fletcher). He faults bioethics for being a liberal project out to acquire “broad social power.” Thus, Smith applauds part of Franklin’s assessment that bioethics is on the outs. However, Smith is not dancing on bioethics’ grave, but remains concerned that in its wake is nothing—no attempt at moral grounding of research: “the virtual moral anarchy dictated by the “golden rule” (he who has the money makes the rules) Franklin describes is even worse.” To Smith, Franklin describes a world of chaos where everyone decides their own morality (subjectivism) which is quite far from his notion of a firm right and wrong grounded in a respect for life (i.e. his interpretation of Christian positions).

Clearly, neither Franklin nor Smith were at the 21st Annual Meeting of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities. Three sessions talked about “artificial intelligence”, 3 covered “citizen science”, 7 fell under “genetics”, 16 were about “reproduction”, and 35 “research ethics” sessions took place. This does not sound like a field that has been left behind the rapid pace of scientific development. However, if Franklin is referring to lack of a national bioethics commission under the Executive Branch, then she may have a point. Still, there are bioethicists serving on science panels in DHHS and the EPA. Many of us are consulting with pharmaceutical companies as they develop more technological approaches to treating disease. Where we are scarcer is in the halls of the big tech companies who are making [un]ethical research decisions. For example, think of Facebook’s emotional contagion study. Another instance is that Google established an ethics group to “consider some of Google’s most complex challenges that arise under our AI Principles, like facial recognition and fairness in machine learning, providing diverse perspectives to inform our work” which included scholars in information technology and ethics. However, the group also included the president of the libertarian Heritage Foundation and public outcry from that move motivated Google to dismantle the group less than a week after it was created.

Franklin’s article also falls into another neoliberal trap—claims that expertise is dead and we can outsource everything to the hive mind. With the rise of the internet and 24-7 access to information, some political corners believe that expertise is dead. This notion forgets that having knowledge is one thing; knowing what to do with it is quite another. Is the data good? It is biased? What does it really tell us? The application of data and information is what we need experts for. The attempt to sow distrust for expertise is an attempt to seize power and rewrite reality (i.e. “fake news”), a technique that has been employed by despotic regimes throughout history.

Franklin may not be aware that in the U.S., revised IRB guidelines recently went into effect. These new rules offer guidance for biobanks and streamlining research review. Of course, it took over 8 years to create and enact these new rules. Laws and regs usually appear in reaction to the events in the world. They are a result of negotiation and public comment. This is the type of democratic ethics of the group that Franklin says is happening, but she does not realize that it is even slower than bioethics’ scholarly responses. Bioethics has worked with regulators but has never been the regulators. We must also recall that the current Administration is anti-regulation: They once stated that for every new reg, two had to be retired. Bioethics has never been responsible for enforcing responsible research. IRBs are not a branch of bioethics—they are a regulatory mechanism for ensuring the safety of scientific subjects. Those of us who serve on IRBs know from experience that what the regulations require often has more to do with paperwork than with ethics.

Franklin and Smith both take issue with bioethics not having a singular vision of right and wrong, but rather being interdisciplinary and multiperspectival. The engagement of the humanities, fine arts, and social sciences have improved bioethics, not made it irrelevant. Bioethics now has tools that offer deeper understanding of critical issues and understanding new perspectives: Disability studies, LGBQT critiques, and feminist ethics have all permitted more understanding and more inclusivity. As I said earlier, bioethics never had “the one right answer” to moral problems. Conservative bioethics thinks it does and that is incredibly dangerous.

One last criticism often lobbed at bioethics is that we started as an outsider, activist force trying to change the establishment and now we are the insider, a part of the establishment. That is the nature of all fields, though. In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn discusses how most science is about making facts and observations fit the current theory of science. It is only when enough facts do not fit the theory that a revolution takes place and a new theory is adopted. Such revolutions are rare. Bioethics is the same. We began as a revolutionary force to help patients become partners in their healthcare and to provide protection for human research subjects. We embraced the Principles (love them or hate them, there they are). Bioethics started as revolutionary and now we do “normal science” in the Kuhnian sense. That is the nature of an evolving field. Yes, bioethics has grown and split into specialties: clinical ethics, (more and more looking like a subspecialty of medicine) research ethics (often dependent on grant (CTSA) funding), neuroethics, genethics (the last two also deriving out of federal funding mechanisms), but there are still some generalists around who wonder if normal bioethics continues to work (for example, the consistent call for a bioethics of population health and social justice rather than just patient-provider issues suggests it might be time for a new theory).

Franklin says, “The implication of this new model [non-expert, distributed ethics] is that the most ethical science is the most sociable one, and thus that scientific excellence depends on greater inclusivity. We are better together — we must all be ethicists now.” While public opinion may be one factor in thinking about ethics (I know many would say it is irrelevant to normative thinking), regulations, and policy, that is not the same as bioethics abandoning research. If ethics was as simple as what the majority believes, then we could solve our problems with a Facebook poll. But it is not easy and these decisions are complicated and nuanced. Bioethicists have expertise to understand and contextualize these issues. Franklin’s article leaves me believing that perhaps bioethics has been complacent. In the past, we were invited into the halls of power to help make decisions, but our dance card is more open than it used to be. Part of that is the modern anti-expert zeitgeist. With more research happening in different places that do not fall under regulatory authority, good ethics becomes more important than ever. If we are not invited to the ball, we need to show up anyway through our writing, our activism, and demanding to be heard. We need to help people develop good moral character to make better choices. Franklin isn’t calling for us to lay down, she’s calling for us to stand tall.