by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

In my critical studies of bioethics undergraduate capstone class, the very last lecture examines the question of whether a person must be ethical to be an ethicist. Can a person who is personally abhorrent (say a murderer, someone who cheats on their taxes, etc.) professionally practice as a bioethicist? In general, the students end up believing that to be a professional ethicist, one must be a person of ethical character, which would be reflected in their personal life. A recent study by two graduate students asked this same question of ethics professors in German-speaking universities. They conclude, “While ethicists showed stronger normative attitudes, they did not differ in their moral behavior or attitude-behavior consistency.” In other words, ethicists may expect more in regards to normative behavior, but they do not act better than anyone else.

Philipp Schönegger is a graduate student in empirical philosophy at the University of St. Andrews and University of Stirling. Johannes Wagner is a graduate student in psychology at the University of Graz. Their study was a replication of a 2014 project in the United States by Eric Schwitzgebel and Joshua Rust, which I will discuss in a moment. First, both papers define an “ethicist” as a philosopher who studies ethics. In the world of bioethics, most practitioners would be excluded as an ethicistsince most people in bioethics do not have PhDs in philosophy. My PhD in medical humanities would exclude me. Anyone with an MD and a masters in bioethics who has been working in the field for a decade would also be excluded. In bioethics, we come from diverse trainings and perspectives including literature, art, history, anthropology, sociology, law, and more. None of these people would be part of the study. Thus, people who are in clinical bioethics—the actual application of ethics to everyday [health care] life would not be questioned. Only people who practice more theoretical ethics would be included. Also consider that the control group in these papers are professors (just not in philosophy or ethics) and it is possible that being a professor is the variable that affects notions of normative ethics and behavior.

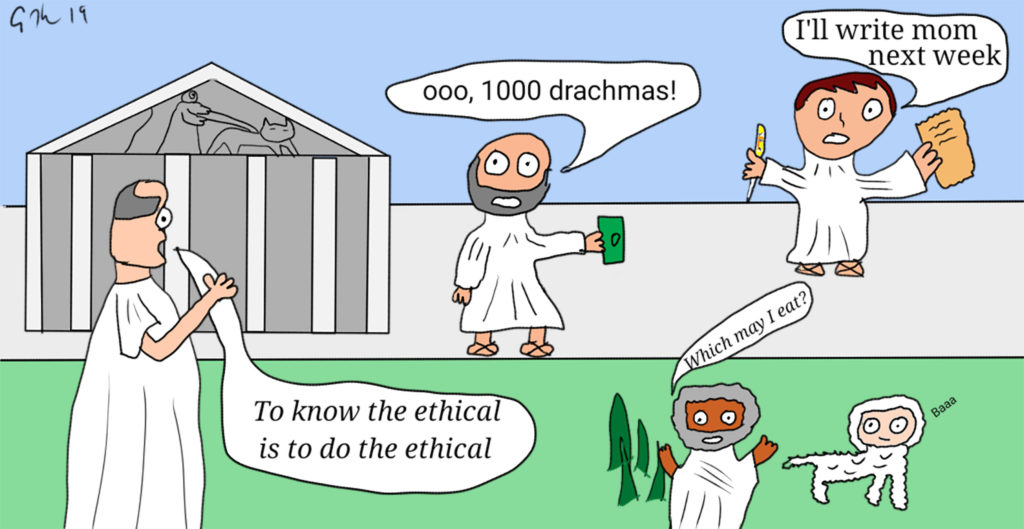

Second, both studies have a limited notion of what is ethical behavior. Schwitzgebel and Rust chose to ask about the theft of $1000 (€1000 in the 2019 study), membership in an academic society, voting in elections, staying in touch with one’s mother, vegetarianism, organ and blood donation, responding to student emails, donating to charity, and honesty in answering surveys. The surveys first asked whether these behaviors were ethical (Likert scale 1-9). While the survey did allow the respondent to indicate whether a behavior was ethical, the meta question of whether voting in an election is an example of being ethical or behaving ethically is not asked. The survey writers force us to assume that these 10 behaviors are criteria of an ethical life, even though they do not state in the papers from where these 10 exemplars come.

The second section of the surveys asked about the respondents’ behavior—how long since you’ve spoke to your mother, how much did you give in charity (percent of salary), how many elections have you voted in. In the 2014 study, some self-reported behaviors were then checked against independent records. For example, one might report voting in the last 5 elections, but a check of voting records might show the participant only voted in 3. Similarly, a person may say that paying dues in their academic association is important (Part 1) and that they are currently a dues-paying member (Part 2), but a check of the American Philosophical Association (APA) records would prove or disprove that claim. (Of course, the checks were limited since the researchers only had voting records from certain states and only from the APA). The 2019 study did not do an independent check. What the researchers is a foundation of bioethics—that context matters. For example, one might have answered it is important to call your mother every week, but they have not called their mother in years. What is not captured is that the respondent’s mother died 5 years ago. Or I might believe it is important to donate blood but I have not donated in a decade. What is not captured is that it is basically illegal for a gay man to donate blood in the U.S. Thus, not following through on a behavior identified as ethical in Part 1 may be due to reasons completely outside of the respondent’s control.

Third, the authors conclude the conclusions that ethicists are no more moral than other professors, but that is not reflected in their results. For example, in the 2019 publication, ethicists are not only more likely to believe meat-eating is wrong, they are also more likely not to eat meat. In most questions on both surveys, ethicists are more likely to have higher expectations of normative behavior (expect more calls to mom, or giving a greater percent of income to charity). But in many of those areas, they are less likely to behave much differently than non-ethicist peers. Because ethicists expect more of themselves, they may be more aware of their shortcomings. Neither survey asked whether the respondents viewed themselves as ethical, just evidence of behavior among a list of arbitrary topics. In bioethics, I would expect a difference in behavior where there was a potential harm to another person (eating meat requiring killing other creatures) versus ones with more esoteric harms given bioethics focus on people rather than concepts.

Fourth, this study represents what some in bioethics have called “the empirical turn” where more and more bioethics scholars are engaging in descriptive work. The problem is that many of these studies are done poorly because few in bioethics have the social science training to design an empirical research protocol and analyze the data appropriately. For example, a number of bioethics surveys have simply asked a pool of people on Facebook to answer some questions. Because Facebook is a narrow (in age, socioeconomics, and reach) audience, findings are not generalizable beyond the population studied. As grad students in empirical disciplines, Schönegger and Wagner may have the training to do this work, but since they more or less just copied the protocol from the 2014 study, that would not necessarily be reflected in this work. What about the original researchers? Schwitzgebel is a professor of philosophy at University of California Riverside with a PhD in philosophy from UC Berkeley. While he is well published, his CV offers no hints of his training in quantitative or qualitative research methods. Rust was a grad student at Riverside at the time of the study, and is now a professor of philosophy at Stetson University. His bio states that he has had several articles in “empirical philosophy” but there is no indication of his training or practice in such research methods.

In many ways, the empirical turn is a problem because bad studies are worse than no studies (consider the Wakefield autism paper as an example). In the 2014 study, only simple statistics were used—percentages and means on a Likert scale. In fact, this paper lacks a discussion of the statistical methods used in analysis. The problem is that means is probably not the correct statistical analysis for this sort of survey. This issue was actually one of my comprehensive examination questions for my advancement to PhD candidacy. One member of my committee was a renowned social science research methods expert and in her question to me, I was to analyze a 1993 study that purported to show no convergence on bioethicists’ views on cases. The authors in this article had backgrounds in medicine (and practice in bioethics consulting) and sociology. This study presented four PVS scenarios and asked respondents to choose from a multiple-choice list of potential recommendations. In three of the scenarios, the authors conclude that there was no consensus; the answers were all over the place. Their analysis used a means calculation. However, the intent of the question on my exam was whether that was the correct way to analyze the data. What my examiner was pointing out was that if one did a modal analysis (count the number of people who had chosen each of the potential answers and look at which one was chosen the most), that indeed there was a clear consensus on answers for the scenarios. Reanalyzing the data showed that in fact, ethicists value patient wishes most highly in making recommendations. (We discussed whether there was a duty to report our discovery to the journal editor, which I was supposed to do and never did. I suppose 19 years later is better than never).

The questions did ask a respondent to rank from 1-9 how important or valuable a topic was (like calling your mom). This is not scientific nor an objective measure. Is there a real different between choosing 7 and 8? Not really. Thus, analyzing means is meaningless because the numbers are meaningless–an attempt to quantify what is not truly quantifiable. If instead, the researchers asked “How many times were week is it ethical to call your mother” a selection of 7 times or 8 times is quantifiably different, though I am not sure that it would have any ethical meaning. The 2019 study has a more rigorous discussion of statistics, where they used an ANOVA. However, an ANOVA uses means and thus can miss the modal effect that I saw in my comprehensive examination. Plus, choosing how important it is (1-9), does not get more objective or meaningful no matter what statistics one uses.

Fourth, another problem with these studies is the reliance on self-reporting. While some answers could be independently verified, the vast majority could not. Even though self report is often used in social science and medical studies, it is notoriously unreliable. Respondents often want the researcher to like them, so they choose the responses that they think the researcher wants.

Fifth, the 2014 and 2019 studies begin with an assumption that knowing the right thing leads to doing the right thing. The naturalistic fallacy teaches us that people’s behaviors do not tell you what they think is right. Therefore, why should knowing what they think is right be predictive of their behavior? These studies show it does not. Thus, the lessons from these articles isn’t what philosophical-ethicist professors believe and do as compared to other professors, but rather that people behave in ways other than what they believe is right. Since the studies did not ask people why, we do not know.

I am left asking two questions: Do these studies actually show anything real? And would there be value in doing a well-designed version of the study among bioethicists. I think that any attempt to simplify the complexity of ethical decision-making into a multiple choice selection or a Likert scale misses the nuances that are at the heart of difficult decisions. The 2014 and 2019 studies focus on whether philosophical-ethicists are more likely to walk their talk than other professors. Given the greater diversity and focus on application of bioethics, these two studies would not provide a template. The real question is whether a bioethics approach helps patients, families, and care providers to make difficult decisions. And that won’t be answered on a scale of 1-9.