by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

In the 2011 film, In Time, people are implanted with a digital clock that tells them how long they will live. When the clock reaches 00:00, the person dies. The clock activates when they turn 25, though additional time can be purchased to extend their life. The film explores social disparity and how people behave as they know their life is ending.

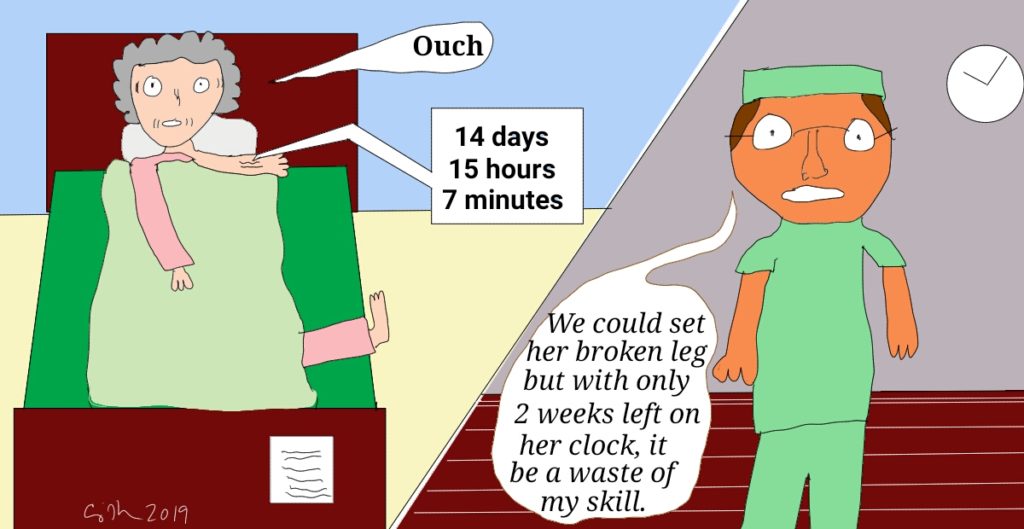

Imagine if there was a clock or a test that could predict when a person would die. Would people live their lives any differently? Would medical care be withheld from them at a certain stage?

Researchers have reported developing a metabolic test that screens for 14 biomarkers and are correlated with a strong likelihood of dying in 5 to 10 years. Although not available yet, we are on the cusp of having a test that can state whether a person will die in the next decade. The biomarkers look at metabolism of fats, glycolysis, fluid balance and inflammation. The researchers were seeking a more precise and accurate test than conventional predictors of mortality risk such as blood pressure, cholesterol, gait and grip strength. The new test is 83% accurate and was developed by looking at 44,168 subject records. One note of caution is that the test has been applied to populations, but has not yet been looked at in predicting whether an individual person will die.

In some ways, this test is not unique. For people over the age of 75, a medical exam to determine frailty is accurate for predicting death within one year. The impetus for mortality medical tests is twofold: (a) to help patients and their families to make better medical decisions (how much care? For how long? How much suffering?) and (b) to save money. Studies have shown that 25% of all Medicare spending is on patients who are in their last year of life. The implication is that such spending is “futile” and “spurious”. Of course, one does not know that a person is in their last year of life until after they have died and often that last year is when a person is sickest. But if there was a predictive test, then we might know the final year in advance. If we knew with 83% certainty that a person was doing to die, would we be impelled to provide them less medicine to save money?

In some ways, this test is not unique. For people over the age of 75, a medical exam to determine frailty is accurate for predicting death within one year. The impetus for mortality medical tests is twofold: (a) to help patients and their families to make better medical decisions (how much care? For how long? How much suffering?) and (b) to save money. Studies have shown that 25% of all Medicare spending is on patients who are in their last year of life. The implication is that such spending is “futile” and “spurious”. Of course, one does not know that a person is in their last year of life until after they have died and often that last year is when a person is sickest. But if there was a predictive test, then we might know the final year in advance. If we knew with 83% certainty that a person was doing to die, would we be impelled to provide them less medicine to save money?

There are two ways of thinking about this issue: (a) That health care providers and insurers would deny care or treat less and (b) that patients and families would choose less care. The implication is that if we could identify who is in the last year of life, then we could save money by denying them care (health insurance not covering procedures; doctors not offering drugs or treatment). Whether that would happen and whether cutting of care to people who are in their final year of life is ethical are separate questions. The first is an empirical concern. The second is normative: Even if a patient is diagnosed as frail or a patient is sick, it is considered unethical to withhold potentially life-saving and comforting medical treatment from them. The same should also be true for someone who has had a death test.

On the other side, would a patient and family make different choices if they had test results that proved death was imminent (in the next decade)? A lot might depend on the patient’s current health condition. For example, might a positive death test and a diagnosis of cancer lead to more decisions not to treat? Might a negative death test and a diagnosis of cancer lead to more decisions to treat? In my clinical ethics consultation experiences, even when armed with evidence-based prognostic information, families make decisions based on emotion and their values rather than the clinical evidence. I could be wrong, but I do not think the additional information from a death test is likely to change many patient and family choices. Even today without a test, many people know when they are in a life limiting situation. The test would simply extend the period of knowing from days or a year to a decade.

What is not clear is whether the results of the biomarker test show what is fated (you are going to die in the next 10 years no matter what) or if one can act to change the biomarkers and reduce one’s risk of death (nudge a number here or there and you are out of the danger zone). I have stated on this blog and been quoted elsewhere as being against predictive tests to show a disease for which there is no preventive treatment. My position against predictive Alzheimer’s testing is in large part because there is no action one can take to forestall the disease. But the death test might have this power—change your habits, see a doctor, and you might be able to see the additional life your healthy actions create. A death test would generate the same potential stress as the Alzheimer’s test, but with the difference that one might be able to change behavior and live longer. That difference argues in favor of the test. The danger, as mentioned above, is if such a test is used to restrict access to health insurance and medical care based on thinking that the person is going to die anyway, even if that time is 5 to 10 years away.

There are potential social implications to the results of such a test as well. Might a person be denied a job for which they applied because they are likely to die in the next few years (why waste the training time)? Might they be refused life insurance because the payoff would be too soon? Might they find health insurance policies restricting types of conditions or periods of time that would be covered? Might an adoption agency refuse a child to a person whose death tests shows demise before the child would grow up? One could argue that these tests would have to be covered by privacy to prevent these scenarios, the reality is that medical privacy is always at risk. Just this week, medical organizations reported a risk of privacy loss by using commercial fitness and health products. In a society that struggles with age discrimination, we are assured of facing problems of death discrimination if such tests come to the market.

If the purpose of a death test is to allow one to think about their demise and prepare for it, there are simpler methods that already exist. You can download a death calendar app to your phone that will display your likely date of death based on your sex, age, and health habits (diet, exercise, hygiene, tobacco/alcohol/coffee consumption, exposure to air pollution). As this app is meant to be “for entertainment purposes only” its accuracy and algorithm is certainly not tested or trustworthy. But, you can have the In Time experience by seeing how long you are predicted to live every time you turn on your phone. Using even less information (smoking, age, sex), Death Clock offers a reminder that you won’t live forever. Yet another app (WeCroak) provides reminders of your demise by sending daily meditations on dying.

These apps serve the same purpose but forgo the potential ethical downside of discrimination, stress, and altered medical decision-making. Spending time each day thinking about death is advised by the Dalai Lama: “You have to practice morality, concentrated meditation, and wisdom on a daily basis.” Would you take a death test?