This editorial appears in the February Issue of the American Journal of Bioethics

Despite significant promise in preliminary (i.e., proof-of-concept) stages, artificial intelligence (AI) sometimes fails to deliver meaningful impact in real-world environments on the metrics that matter most to patients, clinicians, and policymakers. Challenges arise not only from technical limitations but also from poor usability and misalignment with real-world clinical workflows. Recognizing this gap, usefulness has emerged as a key principle for evaluating AI systems. According to CHAI’s Responsible AI Guide, an AI solution is considered useful when it provides a tangible benefit to healthcare delivery and demonstrates not only validity and reliability but also usability. The Coalition for Health AI (CHAI) has prioritized usefulness as one of five essential focus areas for trustworthy AI, alongside fairness, safety, transparency, and security and privacy. This paper outlines the key insights from CHAI’s Usefulness Workgroup.

From a bioethical perspective, usefulness closely tracks with the principle of beneficence. An intervention that is accurate but unusable—for example, a tool misaligned with a specific care context—may fail to deliver meaningful benefit despite technical promise. In this sense, usefulness functions as the ethical complement to non-maleficence, asking not only whether AI avoids harm, but whether it reliably contributes to patient wellbeing.

CHAI’s approach to defining usefulness was shaped by input from a diverse set of stakeholders, including clinicians, developers, regulators, healthcare administrators, and patient advocates. Through an iterative consensus-based process—literature review, workgroup discussions, community-wide surveys, expert convenings, and independent review—CHAI synthesized a shared understanding of what makes AI useful in healthcare. Central challenges are ensuring that AI solutions are integrated seamlessly into clinical workflows, remain actionable for end users, and provide meaningful, measurable benefits. The consensus-driven guidelines offer a structured pathway for people developing AI solutions to achieve these three attributes. This requires that AI is thought about as a system made up of the AI model and interface as well as the clinical and/or operational workflow in the environment that enables safe and effective use. These guidelines help bridge the gap between technical innovation and practical implementation, advancing the field by providing insights developed through input from diverse stakeholders, which can advance AI toward the improvement of health care. Below we highlight some of the key considerations identified through this iterative, consensus-based engagement process. Additional details on the methods for developing the considerations have been reported elsewhere.

Overarching Considerations

Defining the Problem

The first, and most critical, step is defining the problem to be solved and evaluating if using AI is the right approach to address that problem. To do this, developers and program managers should engage early in human-centered design to avoid the pitfall of poor problem identification. While AI has the potential to solve many problems in healthcare, many problems do not require, nor are they best solved with AI solutions. It is important to understand the strengths and limitations of AI and only apply it when AI is fit for purpose.

Organizations should assess the overall operations of an enterprise and identify the most likely cost and value levers that could plausibly be impacted by AI solutions. This involves both a thorough assessment of the status quo—defining a basis from which improvement can be measured—as well as specific opportunities for AI integration to potentially improve the current workflow. Often referred to as ‘delivery science’ leveraging work system analysis, design thinking, process improvement, and/or implementation science, this problem definition phase requires proactively imagining the workflow that needs to execute for an AI tool to address the problem. For example, after an AI model flags a patient as high risk of readmission, what specific steps should the receiver of that prediction be expected to take? An effector arm may be necessary for a solution to achieve intended outcomes. For example, a deterioration index is likely to be more effective when paired with a 24 hr rapid response team. These resources need to be identified early in the design process. The problem definition phase can also comprise drafting representative evaluation samples and explicitly defining the input and output of the system. This simple construct is powerful and allows further design investigation to be grounded. The evaluation samples can be from real or synthetic sources, covering multiple dimensions and thus comprehensively defining the problem.

Assessing Benefits, Risks, and Costs

Once the problem and corresponding AI solution are identified, the next step is assessing the benefits, risks, and costs. For instance: What is the magnitude and frequency of the risks and benefits? Who will benefit from the AI? What roles and tasks may be negatively impacted by the tool? What are the risks if the AI is incorrect, and the end users accept AI recommendations unintentionally? While difficult to estimate, evaluating the number of workflows affected, the impact of AI on workflow efficiency, and the ability to integrate in existing digital workflows can help approximate deployment costs. Once the workflows are identified, it is possible to perform simulations using open-source software that estimates achievable benefit considering work capacity constraints.

There is growing recognition of the environmental costs of AI models; this, along with other cost and risk impacts should be included in a model to arrive at a “total cost of ownership.” This cost evaluation model is increasingly adopted, because it aims to take into consideration the multi-dimensional nature of AI and the layers of costs associated with designing and implementing AI solutions in complex enterprises. A similar model should be applied on the benefits side to estimate the expected value of AI solutions over time. With both the expected cost and expected value estimated, an organization can start to measure and track the return on investment (ROI) of AI. It is fully reasonable to assume that the fiscal capacity of each deployment may differ dramatically. For instance, a low-resource site may require off-site subscription models, while high-resource site may see the cost of compute-intensive models with continuous training as cost effective.

Workflow Integration

Workflow integration should be considered and assessed throughout the AI lifecycle. In our survey of the CHAI community at large, AI integration in workflow was rated as the most important issue across the AI lifecycle. Workflow integration is dependent on a technology’s fit within the sequence and flow of tasks, people, information, and tools as well as the broader work system at the individual, team, and organizational levels. Poor integration of technologies into clinical workflows can lead to frustration, low acceptance or abandonment, workarounds, and increased workload and cognitive burden. As such, it is no surprise that workflow integration is essential for useful, usable, and efficacious AI.

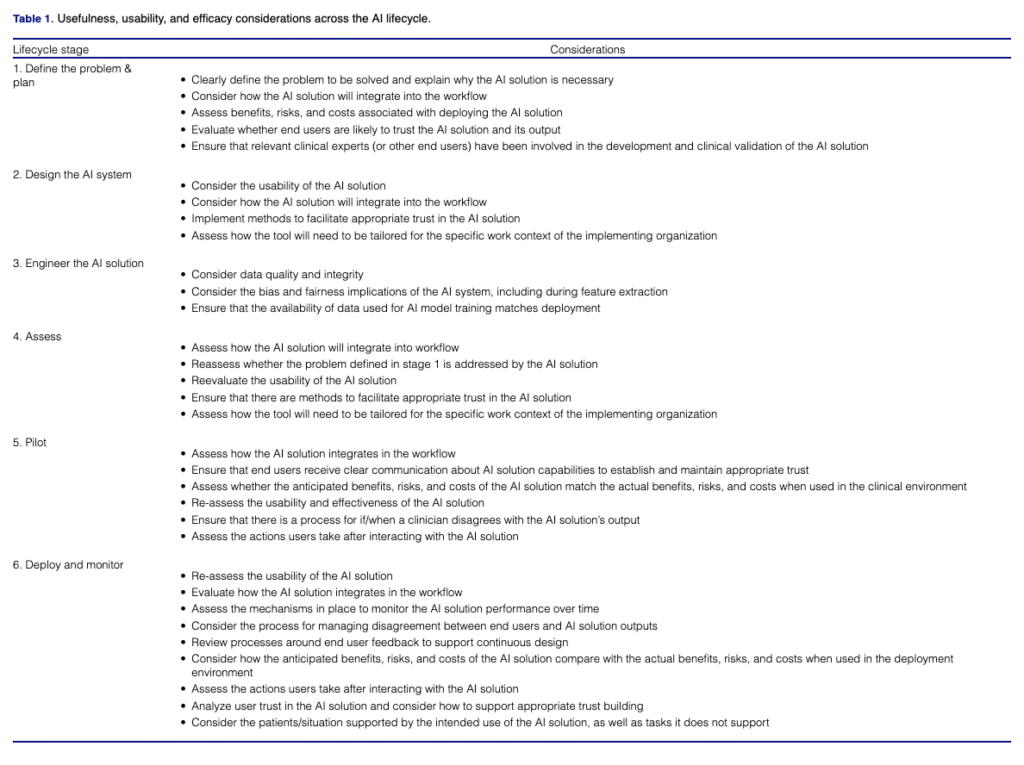

Individuals trained in human factors engineering, user experience, and implementation science should be involved in studying and redesigning current workflows to accommodate the new AI tool; this should begin early at stage 1 (see table 1) with continual assessment throughout development and after implementation. End users should be actively and meaningfully engaged in the human-centered design process. Additionally, workforce simulations can supplement qualitative assessments of workflow. To realize the benefits of AI, it is essential that the AI truly supports, rather than hinders, clinical (and other end user) work. This means that information provided by AI must be both accurate and timely to enable actionable information that augments an existing clinical workflow. Workflow integration can be simulated by implementing digital twins of the environments. This concept allows developers to better understand the implications of the AI systems without a full costly implementation. Without thoughtful workflow integration, output from AI-based solutions have the potential to contribute to burden on the clinician, continued care gaps or increased liability for the healthcare delivery organization.

When usefulness is insufficiently addressed, the consequences are not merely technical or operational. Poorly integrated AI solutions can exacerbate inequities in care delivery, contribute to clinician moral distress, and introduce new risks to patients through delayed, ignored, or misapplied recommendations. In such cases, AI may formally promise benefit while substantively undermining beneficence and non-maleficence.

Tailoring for Local Context

Going hand-in-hand with workflow integration, AI tools need to be adapted for the local context of use, in particular when implementing an AI system into a new setting. Several studies have demonstrated the need to validate AI solutions with local data as AI performance can vary from organization to organization. This aligns with the lifecycle stage 2 consideration “assess differences between development and implementation environments”. Yet, tailoring for local context goes well beyond the data. The entire sociotechnical system including the people, tasks, tools and technologies, physical environment, and organizational context need to be taken into account for implementation success. Usability is not an inherent quality of a system, rather it is an outcome of use within a specific work context. Therefore, a highly useful and usable AI-driven solution in one setting will not guarantee the same result when translated. Understanding local context must also include careful attention to workflow integration, as fit within local workflows is essential for successful AI adoption.

Trust

End users trust of AI is a multifaceted, important consideration across the development lifecycle. Trust affects end user reliance on systems, especially in complex settings with incomplete information. AI should be designed to support appropriate trust, meaning trust depends on the context of use and the AI’s purpose, process, and performance in that specific context and how the human might team with the AI model. The interface design and broader system architecture can support or hinder appropriate trust by end-users. Healthcare delivery organizations should also build trust in these solutions with their patient population. The impact of AI technology in the patients’ healthcare journey must be incorporated into the usefulness assessment. If not, harm to the patient could occur in the form of financial toxicity or other adverse outcomes. While some research has provided methods to inform the design of AI for appropriate trust, more work is needed in this area. Designers can communicate AI capabilities or limitations to end users through methods such as model fact labels, performance indicators, or system transparency elements. These are particularly beneficial when the AI solution employed relies on less interpretable “black-box’ methodology. Monitoring and incorporating end-user feedback into the design of AI can also enhance trust. Lastly, developing clinician and other end user competencies in AI can increase engagement among clinician stakeholders and enable appropriate trust.

Pilot and Deploy

The pilot and deployment phases provide an opportunity to verify whether the cost, benefit, and risk estimates in earlier stages are in line with their actual values. These steps can also validate whether end-user input and perceptions are being satisfactorily addressed in the real-world setting. Quantitative estimates of efficacy based on RCTs or quasi-experimental designs will, in general, be less biased than those based on observational studies. Stepped wedge study designs and difference-in-difference methods are increasingly popular to this end. These early values can also help establish benchmarks for comparison once the AI solution is being monitored in later stages. Generation of evidence showing effectiveness and positive outcomes is necessary to build trust among clinicians/end users but also medical societies and payers. This evidence generation will be necessary to advocate for reimbursement.

Monitor AI Solution Performance over Time

Despite a robust design and implementation process, new, unexpected issues are likely to occur following implementation of AI due to the nature of complex sociotechnical systems. AI performance can change throughout its use due to several factors such as new policies and patient populations, dataset shifts, and the impact of the model on predicted outcomes. To ensure reliability and maintain usefulness, usability, and efficacy, AI tools should be continually monitored after implementation. Proactive systems for monitoring should focus not only on AI performance, but also its impact on process measures and outcomes, and careful attention should be made to ensure fair and unbiased performance is delivered across various demographic subgroups. Additionally, mechanisms should be put in place to solicit and deploy end-user feedback on AI tools. For example, quick feedback mechanisms incorporated directly into interfaces (e.g., with an embedded Likert scale) can successfully gather real-time end-user feedback. Systems for adverse event reporting should also be in-place to gather data on safety issues impacting quality of care.

Conclusion

Even the most accurate and well-intentioned AI tools will fail to improve healthcare if they are not used by clinicians and other end users. Usefulness—defined by real-world impact, workflow fit, and contextual adaptability—must be a central benchmark for evaluating AI. Considerations such as usability, trust, and workflow integration, must be considered early and throughout development, rather than deferred to late-stage testing or post-launch adjustments. Early investment in these areas to proactively identify and resolve any issues with the AI design can enable more meaningful engagement with end users, reduces costly redesigns, and increases the likelihood that AI tools will be successfully adopted, sustained, and deliver meaningful clinical value. By embedding human-centered design and usability evaluation into every stage of development and implementation, health systems can bridge the gap between innovation and meaningful clinical benefit. Furthermore, by treating usefulness as an ethical obligation—and not merely a technical concern—AI governance can more fully honor the principle of beneficence, ensuring that AI-enabled care delivers meaningful benefits in real clinical settings.

Megan E. Salwei, PhD; Keith Morse, MD, MBA; Suchi Saria, PhD; Nigam H. Shah, PhD; Armando Bedoya, MD; Molly Beyer, MD; Alejandro Muñoz del Rio, PhD; Dennis Chornenky, MBA; Anthony Lin, MD; Sawan Ruparel; Daniel Kortsch, MD; Priyank Barbarooah; Morgan Hanger; Ashley N. Beecy, MD; Matthew Elmore, PhD & Nicoleta J. Economou-Zavlanos, PhD