The following editorial can be found in the January 2024 issue of American Journal of Bioethics.

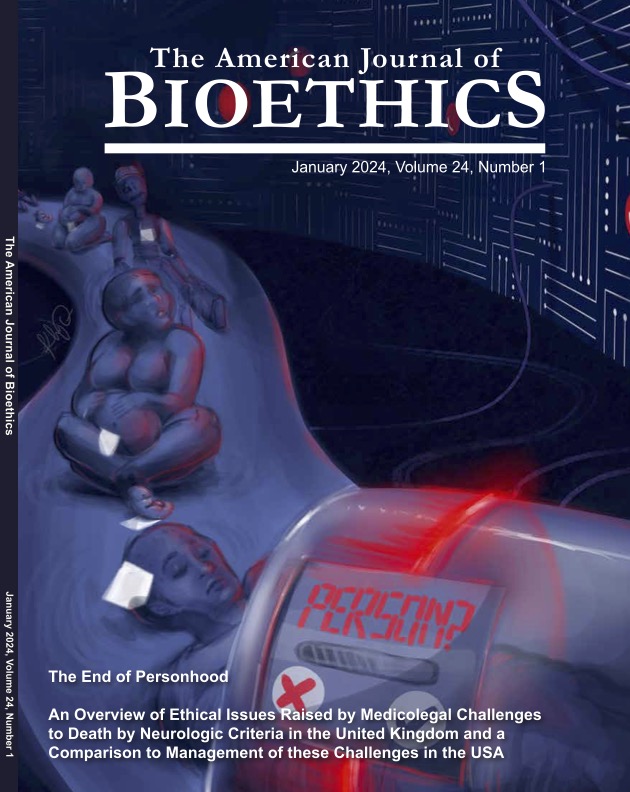

We were delighted to be asked by the editors of the American Journal of Bioethics to provide this editorial in response to Dr. Ariane Lewis’s paper “An Overview of Ethical Issues Raised by Medicolegal Challenges to Death by Neurologic Criteria in the United Kingdom and a Comparison to Management of These Challenges in the USA” being published in this January 2024 issue. We serve as chair, vice chair, and reporter of the Uniform Law Commission’s Drafting Committee to Revise the Uniform Determination of Death Act. That effort, which is now paused, includes incredibly dedicated Commissioners of the Uniform Law Commission (“ULC”), an American Bar Association Advisor, and more than 100 Observers, including Dr. Lewis. We appreciate the opportunity to provide this editorial, writing in our individual capacities and not on behalf of others, including the Drafting Committee or the ULC.

As Dr. Lewis makes plain, determinations of death by neurological criteria (“DNC”) are critically important, as are all determinations of death. Numerically, DNC determinations arise in a small number of all determinations of death. A DNC determination is made only in a hospital setting, not other settings where deaths occur or are declared. Stated simply, this is a function of where ventilators are used. Before the advent of mechanical ventilation, that person would die as a result of circulatory/respiratory failure.

In recent years, less than 30 percent of deaths in the United States are reported as occurring in the hospital setting, with the more than 70 percent of deaths occurring in hospice, nursing home facilities, the home, or elsewhere. In recent years in the United States, DNC represents less than one half of one percent of all deaths, and around two percent of all deaths determined in hospitals.

A few of those DNC determinations have prompted litigation, both in the United States and as explained in Dr. Lewis’ paper, in the United Kingdom. For various reasons that Dr. Lewis highlights, resolution of DNC issues without the need for court involvement is the better way to address these important issues. Among other things, given the significant delay involved and the general lack of medical expertise of the judicial system in this important area, litigation should be a last resort in resolving disputes that may arise in determinations of death by neurological criteria. As Dr. Lewis shares, the Court of Appeal in Battersbee noted that the trial court record in that case did not include “any medical witness who ha[d] diagnosed death.”

Dr. Lewis’ paper provides significant context and detail for court decisions in the United Kingdom addressing the DNC determination. Her paper describes a common law system, with the courts resolving DNC legal issues based on what courts define and without statutory directives. By contrast, since at least the early 1980s, the United States has largely looked to state statutes (enacted by state legislatures and signed by state governors)—not the common law—for the DNC legal standard. In nearly all states, that standard comes from the Uniform Determination of Death Act (“UDDA”), promulgated by the ULC, the American Bar Association, and the American Medical Association in the early 1980s. The UDDA was prompted by similar, but not identical, statutory efforts in the 1970s: (1) the Model Definition of Death Act (ABA 1975); (2) the Uniform Brain Death Act (ULC 1978); and (3) the Model Definition of Death Act (AMA 1979). The text of the UDDA was designed to meet the need for a uniform statutory definition. The UDDA was designed to avoid the vagaries of the common law, with no thought that the common law would do the work just as well or better. In this important respect, the legal approach in the United States in addressing the DNC determination has been quite different from what Dr. Lewis describes in the United Kingdom.

Dr. Lewis notes a proposal, at about this same time, for a statutory definition of death in the United Kingdom. More specifically, she notes “Fifty years ago, [Professor P.D.G.] Skegg advocated for the creation of a statutory definition of death in the UK (Skegg 1976). He noted this was needed to provide clarity in the setting of inconsistent perspectives among both physicians and society about identifying the point of transition from dying to dead, citing that a lack of unanimity would likely persist and neither judge nor jury should be responsible for these deliberations.” If written today, that stated position would continue to ring true. But that position has not, at least so far, apparently carried the day in the United Kingdom legal system.

The advancement of medicine, including in particular the advent of the mechanical ventilator and related technology, led to a significant focus on the DNC determination starting about three generations ago. The UDDA effort was driven by advances in medicine like those noted by the Great Britian Court decisions Dr. Lewis discusses. In Regina v. Malcherek and Steel, consolidated criminal murder cases in which the defendants questioned whether their victims had died, then-Chief Justice Lord Geoffrey Dawson Lane wrote in 1981 that “Modern techniques have undoubtedly resulted in the blurring of many of the conventional and traditional concepts of death.” It is no surprise that early cases in the United Kingdom discussed by Dr. Lewis (particularly Malcherek and Steel) were decided in the early 1980s at about the same time the UDDA was being promulgated and adopted in many states in the United States.

DNC is at the intersection of medicine, law, bioethics, and many other considerations. Dr. Lewis correctly notes that DNC is a medical determination, applying a legal standard. As a subset of how death is determined generally, DNC has the potential to impact us all and is influenced by the human conditions surrounding any determination of death. Additionally, there can, at times, be profound confusion about DNC, as Dr. Lewis’ discussion of the cases from Great Britian suggests.

There is, we believe, a need for updating a broadly accepted and consistently applied definition of death by neurologic criteria. We would also submit that doing so through statutory reforms is more likely to achieve broad societal acceptance. Over the last few years, the ULC’s Drafting Committee to Revise the Uniform Determination of Death Act has worked hard to identify a revised, updated UDDA. The individuals involved in that effort are committed, thoughtful volunteers with varied backgrounds, philosophies, and points of view, many of whom are experts who have long been engaged in academic discourse about the best way to update DNC. The exchange of ideas has been rich and challenging. Listening carefully to the perspectives, desires, and concerns of those individuals, as well as other individuals and groups, it became clear that the search for a broadly accepted revised legal definition of DNC would take additional time for discussion, stakeholder engagement, democratic deliberation, and observation of how changes to generally accepted medical standards would fare in the medical profession and in any potential legal challenges that might follow.

Updating the criteria by which a determination of death should be made is an extremely challenging undertaking, involving legal, medical, philosophical, and other perspectives that can be difficult to square. And revising an existing statutory scheme involves different challenges, and faces different hurdles, than initial drafting in a comparative statutory void. There remains, as Dr. Lewis concludes, “an ongoing need for consideration of steps to prevent and/or improve the management of controversies related to DNC.” We believe that a pause to the existing efforts to revise the UDDA allows democratic deliberation to continue over whether broadly accepted statutory revisions to determinations of death can be achieved.