by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

“I’ve always wanted to try and ensure that, even before having a child and hoping to have children…Two, maximum! But I’ve always thought: this place is borrowed. And, surely, being as intelligent as we all are, or as evolved as we all are supposed to be, we should be able to leave something better behind for the next generation.” – Prince Harry, HRH Duke of Sussex, British Vogue (September 2019)

Recently I read The Uninhabitable Earth by writer David Wallace-Wells, an exploration of the climatic and environmental challenges facing humanity and the entire planet. The message is grim—we are in big trouble regarding the long-term sustainability of complex life on Earth. The author is reluctantly optimistic that we can limit the damage we have created through massive geoengineering and socioeconomic change, but other critics are not so sure since the costs are overwhelming and the politic will is nearly nonexistent. One could dismiss one journalist’s writing as hyperbole; after all, he wants to sell books. However, the book was published around the same time as a new United Nations report on climate change: We have 11 years before the damage caused by climate change is irreversible.

That there will be damage from climate change is certain. The efforts now are to limit that change. Projections hold that the earth will warm between 2 and 5 degrees this century. Two will disrupt the food supply, raise sea levels, create millions upon millions of climate migrations, and lead to the extinction of many species. Five degrees is nearly unfathomable, warmer than the earth has ever been and perhaps unrecoverable (a more likely scenario given the rollback of the Endangered Species Act and other environmental protection laws). Humanity and most complex species would not survive.

No species has had as strong an effect on changing the surface of the planet as humans. We are in the midst of a great extinction event caused by human activity: Changing climate and land use patterns are forcing species to adapt, find new homes or die. Over one million species are currently under threat of extinction. The focus of current responses to limit climate damage come through calls of moving away from a carbon-based economy (think fossil fuels, plastics, carbon taxes), and to develop massive carbon capture projects (expensive and the technology for widescale application does not yet exist). Other efforts talk about sustainability and designing lives that have a smaller impact on the environment (the academic life with its use of computers (power, rare earth metals), paper (cutting down trees), and air travel has a big carbon footprint).

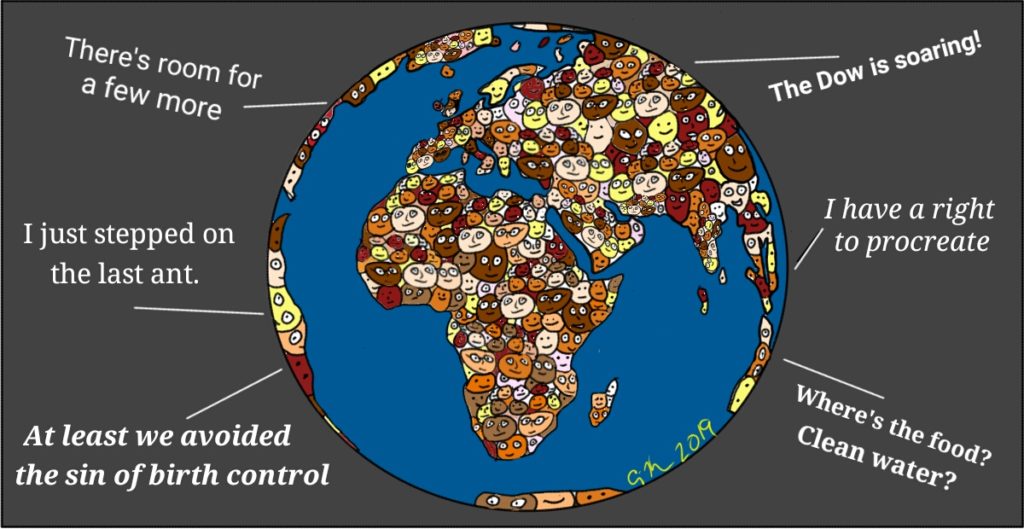

What is missing from this whole conversation is what began the conversation into climate change studies in the first place—are there simply too many humans on the planet? Mid-way through 2019 the world holds nearly 7.6 billion human beings. To put this in perspective, consider that we did not reach 1 billion humans until 1804. The two billion mark was hit in 1927. We reached 7 billion in 2011 and are projected to reach 8 in 2021. By 2050, we will be at nearly 10 billion people. One approach to limiting the effect of humans on the planet is to limit the number of humans.

In 1968, Paul Erlich published The Population Bomb, an incendiary tome that predicted worldwide famine in the next twenty years if human population growth was not controlled. The book has been criticized by many for not anticipating new agricultural technologies that would enable us to grow more food. While the Malthusian approach of the book may have been inaccurate in human populations, the underlying idea that there may be a limit to how many people the earth can support is one we need to revisit.

When talking about limiting population, many people refer to the recently abandoned Chinese one-child policy. In an attempt to curtail a runaway population increase, in 1979 the Chinese government limited couples in many areas to only having one child. The result did slow down population growth, but it also infringed on autonomy, procreative liberty, and led to forced abortions, abandoned children (or sent to other countries for adoption), and a skewed sex ratio (male children were more desirable than female). The state was a strong and coercive force limiting individual choice. The policy ended in 2016, but seems to have created a culture that prefers smaller families.

Facing our environmental challenges suggests a need for a philosophical analysis about having fewer children. An OpEd in the UK’s The Independentsays, “Rather than being taboo, being childfree is something that should be celebrated and valued.” In the U.S. the size of the average family is declining both in ideal and in reality. The birth rate in the US has also been declining year after year. Some of this may be due to more time constraints on families that make it harder to have larger families, the need for both parents to work in two-adult households, the decline of two-adult households, the increase in cost of raising a child (approximately $233,610), and even the zeitgeist of a fear of a diminished future.

Given the challenges facing humanity and Earth, a recent issue of Essays in Philosophy, suggest that there is a duty to not procreate. Three of the essays suggest that being child free should be the norm, that the act of procreation is immoral, that if we have a duty to reduce our carbon footprint that includes a duty to reduce our procreation, and that abortion is acceptable (perhaps necessary) based on what we owe the future. A fourth essay recognizes that people have a biological drive to be parents and offers a solution of co-parenting—many adults raising one child as a response. This last one reminded me of the hero in The Expanse sci fi series who was raised by 8 parents (he is genetically related to all of them through gene engineering).

Bowdoin College philosophy professor Sarah Conly suggests that couples have a right to only one child because of the environmental cost of each human being on the planet: “I’m going to argue here that we don’t have a right to more than one biological child. At this point in time, when the world around us is in so much danger from environmental degradation, doing just as our parents did-having as manychildren as we happen to want is no longer viable. Given the numbers we have now, it’s just not an acceptable option. We are threatened with more population than the planet can bear”. In her book, One Child, Conly says that the state may even be justified in controlling reproduction (see the China example above).

Fewer people means a smaller impact on the environment and a higher level of living for the smaller population. Uncontrolled population growth has a large negative impact in terms of carbon use, land use, water use, and more. Other philosophical arguments, such as those made by Peter Singer, suggest as only a single species, we lack the moral authority to have remade the planet and selected for species that serve our needs while ignoring the needs and interests of the rest of the biome. While environmental ethics has been part of the bioethics discussion for a long time (ASBH has an environmental ethics affinity group and the original meanings of bioethics according to Franz Jahr and Van Rensselear Potter was about examining the relationship between humans and the global environment), it has not been central. In part, U.S. bioethics focuses on the individual and maximizing autonomous decision-making, a position that leaves little room for more expansive communitarian and group-oriented approaches. To deal with climate change, the Anthropocene Extinction, and the survival of biology on Earth requires reducing the emphasis on individual choice. This approach might curtail our freedom to travel (airplane travel is carbon intensive), our freedom to further colonize nature, and may require an authority to curtail our choices that have a negative impact on the environment, including adding to the population. Although the Chinese one-child policy was authoritarian and destructive to personal freedom, it was effective. As a world (yes, this requires world action, not just a single country), creating incentives for people to have one child or to remain child free could take a carrot approach (rather than a stick).

I have no doubt that many, if not most, readers will disagree with this idea of limiting our population and even working to decrease it through attrition (lower birth rates mainly since actions that would kill populations already born are unacceptable morally, ethically, and legally). Reducing the birth rate is a long-term approach that over a few generations will decrease the size of the human population and ultimately decrease our impact on the world. Because this approach is a long term one, it has to be combined with the geoengineering discussed by Wallace-Wells and other programs to reduce our use of resources. We have a decade to complete this project, which means bioethics needs to take up this agenda yesterday.