This editorial appears in the December 2024 issue of the American Journal of Bioethics.

When does an interaction between a mental health clinician and a patient cross the line from a reasonable offer of care to coercion? In a classic account of coercion in psychiatry, Szmukler and Appelbaum build from Wertheimer’s theory of coercion to propose that coercive pressure exists when the clinician makes statements that contain a threat to make a noncompliant patient worse off relative to some “moral baseline.” For example, a patient is coerced if they are told that refusal of care will result in a loss of freedom that the patient has a right to enjoy.

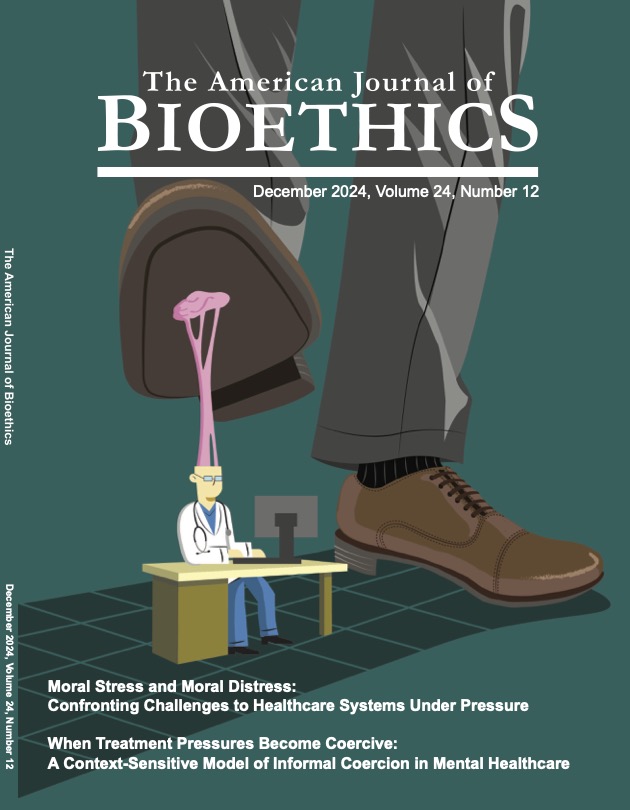

In this issue of AJOB, Hempeler and colleagues argue that this analysis is inadequate. They develop an account of “informal coercion” and suggest that proposals from clinicians are coercive when contextual factors are present that make patients justifiably believe in the presence of a threat even when there is no explicit statement. As they note “due to a fundamental power imbalance between professionals and service users in mental healthcare, contextual factors and service users’ interpretation of communicative interactions play a key role in determining whether the use of treatment pressures is coercive” (75).

We agree with the general idea, but want to further widen the lens through which power imbalance is analyzed. In the vignettes that Hempeler and colleagues offer, identical statements made by a clinician can be understood as more or less coercive depending on whether there are contextual cues in the milieu of care that reasonably could be interpreted by the patient as creating an implicit threat. For example, the presence of a guard at the door and a visible gurney add a threatening context to the clinician’s attempt to persuade a patient (“Alex”) to stay in an inpatient facility when he is initially resistant. As the authors argue, reasonably perceived threats can also exist when patients feel like their clinical team will interfere with their access to future services if they do not comply with a request to attend care. This is the situation their case of Mika illustrates when the psychiatrist mentions her application to an assisted living facility in the same conversation about her reluctance to attend group therapy.

In the authors’ proposed analysis, the perception of coercion depends on a patient being able to decipher the meaning of what their clinician says from other cues in the environment. This is not intended to be a subjective account of whatever the patient feels, but rather to appeal to a standard of what a “reasonable” patient might infer. The “reasonableness” of belief or perception of threat is a core and important feature of the authors’ account. But to what extent can different patients reasonably reach different conclusions about coercion based on their individual circumstances or the history of their mental health experiences? Take for example the statement, “I would really like you to take your antipsychotic medication.” Heard by a wealthier patient who has only ever been treated on a voluntary basis in comfortable, private psychiatric facilities this may sound like an innocuous suggestion, but to an indigent patient who has experience taking psychiatric medications during episodes of involuntary hospitalization in public hospitals it may reasonably not sound like a choice at all. The more general point is that the power dynamics that Hempeler and colleagues observe are not universal, they vary between patients.

In the United States experiences of mistreatment by health care practitioners vary along lines of race, social class, and health insurance status. Patients bring to their medical encounters a set of expectations about how much their treatment will incorporate their preferences, respect their privacy, and humanize their individual experiences. Negative experiences within a patient group have durable effects—a phenomenon observed, for example, in the dramatic decreases in health-seeking behavior and increased medical mistrust among African Americans after the Tuskegee Syphilis study.

Second, and related, the reasonable perception of coercion depends not only on the individual behavior of clinicians, but on the trustworthiness of each individual psychiatric facility writ large. This point is to some extent anticipated by the example of Alex, who in one scenario sees visual evidence to suggest that the inpatient facility will restrain him against his will. However, some organizations and facilities have reputations that transcend any immediate factors in the provider-patient encounter. A recent New York Times exposé describes how a major psychiatric facility chain called Acadia fraudulently and illegally held psychiatric patients against their will as a tactic to increase their length of stay and, ultimately, Acadia’s reimbursement. Acadia staff reportedly were coached to misrepresent patients as being “combative” in clinical notes as a way to justify their continued psychiatric detainment. The immorality of this alleged conduct is beyond question, but it also poses an interesting question—in light of these facts, is it reasonable for any patient at an Acadia facility to perceive that their care is being provided under coercive conditions, no matter how friendly the staff are on an interpersonal level or how welcoming the environment looks?

More broadly, should a background set of institutional facts (like the reputation of the facility for respecting patients autonomy versus fraudulently detaining them against their will) factor into the coercive potential of individual clinical encounters at the facility? As with individual patient characteristics, the issue of the institutional environment, and specifically the institution’s reputation as a trustworthy (or untrustworthy) site of care, adds more nuance to the “contextual analysis” that Hempeler and colleagues recommend. On one level, these points serve to reinforce their argument that treatment pressure can be coercive in light of broader power relations that go beyond individual statements. However, undertaking this analysis is enormously complex in any individual cases, making it difficult to define clear standards for when conduct has crossed into coercion. The complete answer to whether a patient has been coerced might depend on an entire set of facts about the statements and implied threats from the staff, the individual patient’s history, and the institutional environment. In short, what is a “reasonable” or “justified” belief about a perceived threat of being made worse off in some way (i.e., being coerced under the authors’ account) and who decides and how?

It is impossible for any individual clinician to fully inhabit the perspective of their patient so that they entirely understand what expectations and perceptions they and the institution they practice in bring to a particular clinical encounter, but they can make efforts to close that epistemic gap. Thus, the more relevant practical question may be: what would a clinician, acting in good faith and hoping to honor the preferences of patients, do to reasonably avoid the perception of coercion?

A starting point is to ask patients questions—not only to clarify how the patient understands their choices, but also to gain more appreciation for their individual and cultural background and how those factors shape their sense of power relations. Clinicians may also need to account for the institutional history of the place in which they work, including any painful history of neglect, racism, or mistreatment toward patients, and in some cases this may also limit their ability to not be perceived as coercive, even when they act with the best intentions. Finally, limiting coercion is only a starting point toward the deeper problem of justice—dismantling the power imbalance that can color the relationship between the provider and patient. Patients will have fewer reasons to perceive coercion when they are treated as worthy equals to their mental health clinicians.