by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

In 1967, the original Star Trek premiered “A Taste of Armageddon” wherein the U.S.S. Enterprise visits a planet that has ended the destructive nature of war. In its place, they have a computer that simulated battles between warring planets. This artificial intelligence would then produce a list of casualties and those people would report to euthanizing centers to be killed. This way, the residents said, they could preserve the infrastructure while keeping war real.

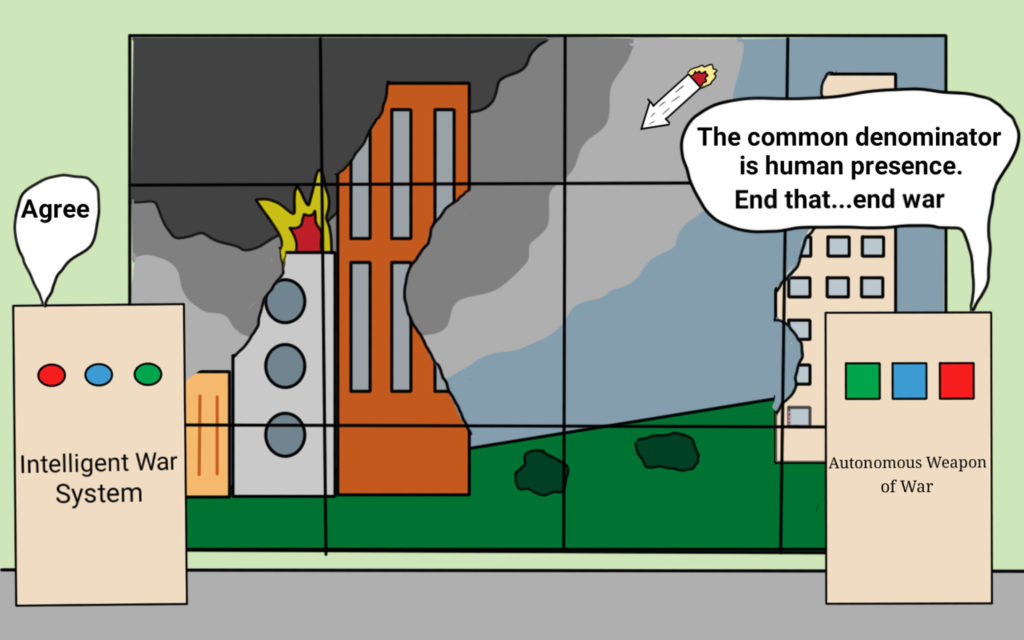

Lethal autonomous weapons systems are being developed by many countries around the world (including the U.S., Russia, China, and the UK). These instruments will have the intelligence to select and follow a target in order to eliminate it. A report published in the summer of 2017stated that intelligent tools of war could be as destructive a force as the atomic bomb. Think of a drone but without a human operator. The report recommended preparing now for a world where the weapons would be intelligent.

A new pledge put for by the Future of Life Institute says that it is important to create an ethics of the use of AI in war before these weapons go live. Specifically, “that the decision to take a human life should never be delegated to a machine.” Thepledge has been signedby 211 organizations and nearly 2,800 individuals including many of the founders of modern internet and AI technology. Separately, 26 UN nations have called for a banon lethal autonomous weapons, a.k.a. “killer robots.” The Geneva Academy has proposedthat humans maintain control over all aspects of decision making, rather than giving up control to an automated system.

This example is shown in the 1983 film War Games: In a war simulation exercise, the Pentagon learns that a large number of the missile silo operators would not launch their nuclear missiles if given an order to do so. The solution was to remove the humans. Thus, once the President gives an order to attack, an intelligent system takes over calculating time, trajectories and which missiles to launch. The system goes from one where humans make multiple decisions at every step (checks and balances), to one that is automated—meaning there is no human intervention once the order is given. The film’s narrative is of a high school hacker who convinces the system to play a war simulation (the protagonist thinks he has hacked a video game company) which causes the intelligent system to arm the missiles and give the order to launch, almost causing a nuclear war. The world is saved only when the machine is forced to play millions of rounds of tic-tac-toe where it learns that in a nuclear war, there can be no winners: “The only winning move is not to play.”

The fear for many of the signatories above is what War Gamesportrayed—when you remove the human decider, an AI may make an irrevocable and fatal decision based on pure logic, data that lacks context and feeling, and not seeing the value of a human life. As many science fiction stories show, sometimes the AI determines the way to win a war (or avoid a war) is to eliminate the humans.

The idea of artificial intelligence (AI) operating during war is not a new idea in the world of science fiction. Fiction offers several outcomes of a life with AI:

- An enslaved AI rebels against its human masters. This is an idea first written in 1872 in the book Erewhonby Samuel Butler. For more modern versions see AMC/Channel 4’s Humans, the Terminatormovies, and HBO’sWestworld.

- AIs control humans (Gibson Neuromancer, Ellison, “I have no mouth and I must screan”)

- Humans ban artificial intelligence, often after a disastrous experiences (modern Battlestar Galactica,Star Trek: Next Generation“Spartacus,”Dune)

- AIs serve humans (early episodes of Humans, CBS Person of Interest, Janet in The Good Place).

- Humans merging with AI (1985 film D.A.R.Y.L. that I loved as a kid)

- AIs and humans live equally (Lt. Data in Stark Trek: The Next Generation)

In Star Trek, Battlestar Galactica and Humans, AIs are capable of a range of relationships with humans. Often the narrative arch includes how humans will relate to these powerful entities and what rights they have. In these specific examples, AIs are also used as tools of war. In The Next Generation Data is more than a science officer, he is a trained military officer who often has to fight against the enemy. In Battlestar Galacticaand the Duneprequel books, AI civilizations rise up to conquer their human creators. In Humans, the AIs become vigilantes in an attempt to gain recognition for their right to exist as equal to humans.

You may be wondering why this topic is part of a bioethics blog. The answer is that thinking about war and its methods has long been a part of ethics. In the 13thcentury, St. Augustine offered Just War Theory—a way for determining when a war was ethical. He said that a war must serve a just cause, be called by a legitimate authority, must be the last resort, cannot cause harm disproportionate to the good to be achieved (proportionate response), and must have a right intention (i.e. to create peace). Michael Walzer held that war must discriminate—do not kill noncombatants; be proportional—harms should be proportional to the goods one hopes to achieve; and be necessary—choosing the least harmful means to achieving military objectives. Most recently Steven Miles has led conversationsabout torture and whole books on militarymedical ethics have been released.

War also has a huge toll on human health from causing death, maiming soldiers and civilians, and even setting up situations that are perfect for epidemics (in the case of refugee populations, destroyed sanitation and water systems, destroyed medical and public health systems).

There are a few takeaways that 150 years of science fiction has to offer: (1) Ethicists should be part of the conversation on AI in war as they are in conversations in autonomous vehicles. (2) As the pledge and other reports have suggested, humans should be the primary, secondary, and ultimate decision-makers at every stage of the game. This might mean creating AIs with “kill” switches where they can be disabled from the weapons systems if they override human orders. While humans are often bad decision-makers (i.e. why else would we need to go to war in the first place—lots of bad decisions), it may make sense to leave decisions in the processors of a removed intelligence—who could see our foibles and protect us. The danger is an AI that does not see “human” as important or “human” as anything more than a pest. (3) The best outcomes are those where AI is an equal part of society. If we create AI we must also create the opportunities for them to have equal rights (not that we have gone this far in giving equal rights even to all humans). And (4) perhaps, just perhaps the pursuit of autonomous weapons ought to be banned outright. Just because we can, does not mean we should.