by September Williams, MD

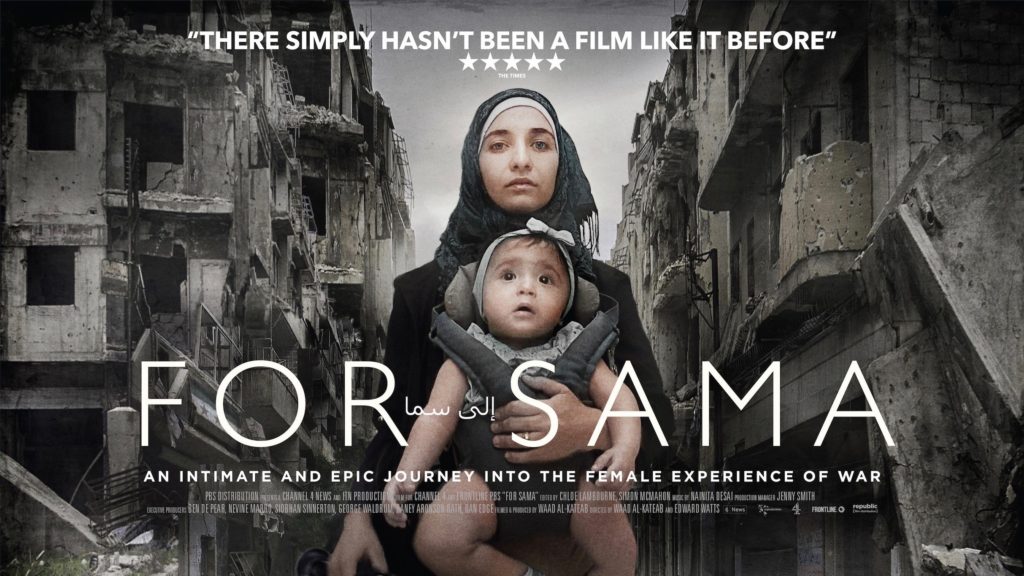

FOR SAMA is a documentary film by International Emmy Award winning journalist and film director, Waad Al-Kateab. The project was brought to fruition with co-director Edward Watts. Director Waad Al-Kateab made this film while she fell in love, got married, was pregnant, and breastfeeding in a war zone rife with humanitarian violations. She did it while her husband, Dr. Hamid Al-Kateab, used every available hand to manage war trauma, first in the remains of bombed hospitals, then in any shelters left standing. FOR SAMA was filmed over five years—in war-torn Aleppo, Syria.

FOR SAMA is essential viewing for bioethicists and clinicians rightfully seeking literacy in the struggle against modern humanitarian violations. This film forces us to double over, fall to our knees and weep—just before we applaud the filmmakers’ relentless skill and courage.

After screening FOR SAMA, during its limited theatrical release this past summer, I rushed to grab my copy of the Médecins Sans Frontières’ (MSF) book, The Practical Guide to Humanitarian International Law . Humanitarian Law is a set of rules which seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict. The MSF book interprets the law in the context of themost vulnerable persons and is organized for easy reference for those needing to make rapid decisions in zones of escalating conflict.

The full body of Humanitarian Law protects persons who are not or are no longer participating in the hostilities and restricts the means and methods of warfare. International Humanitarian Law is also known as “the law of war” or “the law of armed conflict.” It is all well and good that we snicker from the warmth of our safe beds that the title of this collection of laws is oxymoronic. But waiting for perfect, once again, would be the enemy of doing some good.

The bombing of hospitals is in direct defiance of Articles 19 through 23 of the Geneva Conventions. The supervision of Humanitarian Law is entrusted to the International Committee of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. These conventions and their revisions are the source from which the full body of Humanitarian Law derives. In example, the 1949 article 19 states that:

“Fixed establishments and mobile medical units of the Medical Service may in no circumstances be attacked, but shall at all times be respected and protected by the Parties to the conflict. Should they fall into the hands of the adverse Party, their personnel shall be free to pursue their duties, as long as the capturing Power has not itself ensured the necessary care of the wounded and sick found in such establishments and units.”

I owned the copy of the Practical Guide of Humanitarian Law because in the 1990s, I had the opportunity to participate in an MSF assembly session prompted by the armed conflict in Kosovo. The tasks of the session was to clarify and develop policies and procedures for mandatory withdrawal of medical mission by MSF. This is the sort of paradigm and process in which both case based and non-case-based bioethical consideration can be helpful. Potentially abandoning those whom you have sworn an oath to serve is not morally neutral territory.

As we watch the relentless danger, noise and terrorizing of those vulnerable people on screen during FOR SAMA, “First do no harm,” seems a weak mantra in a war zone. Yet, it does hold up under decisional pressure. Morality is easily scrambled in the absence of anticipatory planning for ethically chaotic circumstances. Here, ethically refers to the step-by-step process of instituting moral action. Among the ethical concerns in humanitarian relief work is whether the shear presence of the aid organization endangers the very persons which it seeks to serve. This past October 15, 2019, I woke to a press release from MSF screaming from my email inbox:

“Amid an extremely volatile situation, allowing the launch of Turkish military operations, [initiated with the agreement of the governing executive branch of my own country] the medical humanitarian organization, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) was forced to suspend most of its activities in northeastern Syria and evacuated all its international staff and organizations.”

Not only the Syrian government was bombing hospitals, now also the Turkish and their allies. Active Syrian Hospital destruction was reported early in the Syrian Civil War by the slain London Sunday Times war correspondent Marie Covin and Amnesty International. Seven years after her death, a U.S. Court has confirmed Covin’s death was the result of a targeted killing by the Syrian government in 2012. With her last breath she entered a satellite phone report to her news agency—on the bombing of civilians at a hospital where she had been embedded.

Marie Colvin lost her life in the belief that if people knew about the violation of Humanitarian Law to which patients and healthcare workers were being subjected in Syria, they would do something about it. Filmmaker Waad Al-Kateab, Dr.Hamid Al-Kateab and their baby have risked all to do something about it. The ball is now in the court of the viewers of FOR SAMA.

*Your viewership can determine the breadth and depth of FOR SAMA’s influence.

PLEASE SEE FOR SAMA’s WORLD BROADCAST PREMIERE this Tuesday. November 19, 2019. Check your localFRONTLINE PBS/Channel 4 broadcast: HERE

SEE Campaign: ACTION FOR SAMA: HERE

Also bioethics.net readers are invited to follow the filmmakers and Dr. Kateab through twitter links associated with their names in the first paragraph of this article.

FOR SAMA (2019) | Official Trailer from myVPM on Vimeo.