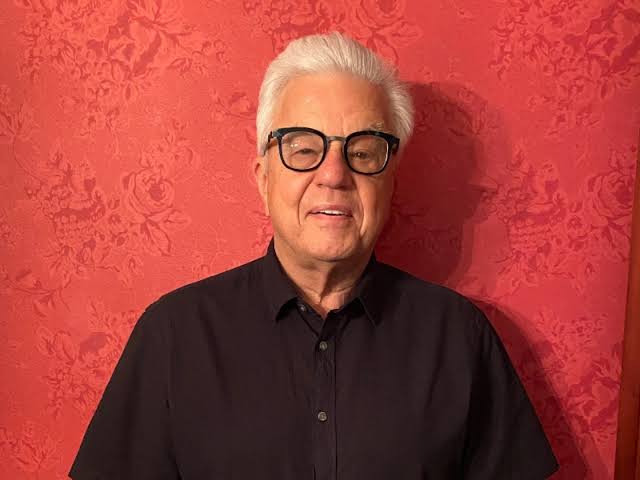

We pay tribute to the late Tom L. Beauchamp, who died February 19, 2025. He was one of the most prolific, important, and influential philosophers in bioethics, but he also made major contributions to other areas of philosophy and practical ethics. He leaves a truly remarkable legacy of intellectual achievement and practical impact.

Background and development. In an intellectual autobiography in the Journal of Medicine and Philosophy in 2020, Tom reflected on an immediately transformative experience that occurred when he, around age 16, read Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country, a novel about life in deeply segregated South Africa. This book opened Tom’s eyes to the injustices in the segregated society of his hometown, Dallas, Texas, and elsewhere in the US in the 1950s. He began to attend Black churches during his high school years, and a few years later when he was a college student at Southern Methodist University (SMU), he and several fellow students planned and conducted sit-ins to protest racial segregation in Dallas. These experiences helped to foster his abiding commitment to social justice.

Tom vacillated between philosophy and religious studies as an academic home for his interests in practical ethics. As an undergraduate at SMU, he studied social science and philosophy but he also took a few courses in the Perkins School of Theology. He then took an MA degree in philosophy at SMU before studying “teaching and research in religion” on a special track at Yale Divinity School, where he and Jim Childress overlapped for a few years. He then earned a PhD degree in philosophy from the Johns Hopkins University.

In 1970, Tom started teaching in the Department of Philosophy at Georgetown University. There, he introduced some courses in practical ethics, and, a few years later, he also became affiliated with the university’s recently established Kennedy Institute of Ethics, which focused mainly on bioethics. When Jim joined the Kennedy Institute’s faculty in 1975, he and Tom soon handled all the lectures on ethical theory and bioethics in the annual Intensive Bioethics Course for practitioners in science, medicine, public policy, etc. They were portrayed in this course as adversaries—Tom as a rule utilitarian, Jim as a rule deontologist. In fact, though, they were beginning to appreciate the overlap and convergence of these and other ethical theories and methods around several ethical principles.

Principles of Biomedical Ethics. At the time, most of the available books in this new field of biomedical ethics or bioethics were unsystematic, except for some religiously based examinations of medical ethics. Most were anthologies organized around a series of ethical problems, such as euthanasia, abortion, and the allocation of scarce medical resources, with limited if any attention to ethical theory and method. Tom and Jim thought it would be helpful to this burgeoning field to develop a framework featuring four ethical principles that were important for different major types of theory. So, in 1979, their Principles of Biomedical Ethics (PBE) became the first book Oxford University Press published in bioethics. Over the next forty-five years, Tom and Jim prepared subsequent editions out of their ongoing conversations with each other and their constant engagement with friendly and unfriendly critics. Altogethereight editions of Principles have appeared, 1979 through 2019, along with ten translations into other languages, and the ninth edition will be published in December 2025.

Jeff notes that it would be difficult to overstate the importance and impact of Principles—it literally was the book that defined our field. We have all read it, studied it, taught it, and discussed it with our colleagues. A substantial proportion of us have written about it, some entire books, and it is one of the few works in bioethics with a serious secondary literature about it, including a range of critics and critiques.

While Tom and Jim did not name their framework, other bioethicists did, calling it, for example, “the four principles approach” (Raanan Gillon) or “principlism” (Danner Clouser and Bernard Gert). Simply put, the framework is pluralistic, in that it presents several prima facie principles that are unranked in advance of situations or types of situations: beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice, and respect for autonomy, along with several derivative or specified rules, including veracity, privacy, confidentiality, and fidelity. Contingent conflicts among these are addressed by balancing (later referred to as constrained balancing) and by specification, which was made fully explicit under the influence of Henry Richardson’s work. Another development over time was an appeal to the common morality, in addition to the convergence of ethical theories. It became an important task to show how common morality and a coherentist method, drawing on a Rawlsian reflective equilibrium, were not only compatible but also fruitful. Still another change over the editions was greater attention to moral status in relation to vulnerable human and nonhuman individuals and populations. Despite some interpretations and critiques, virtue and character have played a major role from the outset but received increased attention in later editions. Throughout, the co-authors saw themselves learning from as well as responding to critics, in an effort to make each subsequent edition all the richer.

The Belmont Report of the National Commission. While Tom and Jim were working on the first edition of PBE, Tom was also serving as a staff philosopher for the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. This first US national bioethics commission was created—because of major scandals such as the government-sponsored studies of untreated syphilis among hundreds of African American males in and around Tuskegee, Alabama—to make recommendations for several areas of research involving human participants. One of this commission’s legislatively mandated tasks was to identify the ethical principles undergirding research involving human subjects. The commission settled on three principles: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. It became Tom’s task to fill out their content and draw their implications for rules and practices for research involving human participants. The result was the famous, foundational Belmont Report, published in 1978.

The enduring importance of this brief report is remarkable. It became an indispensable guide for researchers with human participants and for policy makers in the US and abroad. While there are debates about whether the commission’s reports on research involving different vulnerable populations were more principle-based or casuistical, there are no doubts about the Belmont Report’s overall powerful and extensive impact on the ethics of research with human participants.

A History and Theory of Informed Consent. Another of Tom’s many lasting achievements was A History and Theory of Informed Consent, a product of his collaboration with his wife and fellow renowned bioethics scholar Ruth Faden. Published in 1986, it is a tour de force on the subject, the definitive treatment of both the history and the conceptual foundations of informed consent in both research and clinical practice, and of what those foundations should mean in practice and policy. It is a classic work and arguably the most important book on the subject, then and now. Like many of his generation, Jeff read it cover to cover, in his case first to work on the preparation of the book’s index, then as a student of both Tom and Ruth, and later in his own career in academic bioethics.

Status of and research on animals. Tom had a long-held commitment to taking seriously the interests of both humans and non-human animals, which included advocating for the equivalent of a Belmont Report for animal research. That was realized in part in 1996 when the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) adopted the Sundowner Report, which Tom’s work for NASA helped to instigate and inform, outlining principles for the ethical care and use of animals in research performed by the space agency. In 2011, Tom edited the seminal Oxford Handbook of Animal Ethics with Ray Frey, and in 2020 he brought to fruition the multiyear project he undertook with David DeGrazia and an impressive collection of contributors, Principles of Animal Research Ethics, a book that should become a new standard in the field.

Other works. We have concentrated on Tom’s contributions to bioethics, which also include Medical Ethics (1984), with Laurence McCullough, and, more broadly, his Standing on Principles: Collected Essays (2010). There is much more, as the range of Tom’s intellectual output is remarkably wide. Consider, for instance, his work on David Hume, including Hume and the Problem of Causation (1981), with Alexander Rosenberg, and, as part of his role as co-editor of The Clarendon Edition of the Works of David Hume, An Enquiry concerning the Principles of Morals (1998) and An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding (2000), as well as other works. Tom’s more than 200 articles and book chapters cover a variety of topics in philosophy and in practical ethics. His dozen or so edited or co-edited books include not only bioethics and ethical issues in dying, but also business ethics and epidemiology. Several of these edited or co-edited books have appeared in multiple editions.

Tom as teacher and mentor. Jeff was lucky enough to learn at the knee of this master scholar, having served as a graduate research assistant on a number of Tom’s bioethics and other projects, including the critical editions of Hume’s works, The Virtuous Journalist, Contemporary Issues in Bioethics (with LeRoy Walters), and, as previously noted, A History and Theory of Informed Consent. Tom’s attention to detail was something to behold, and his productivity bordered on superhuman. But it somehow came with patience and good humor, and always a willingness to teach.

Tom was not only the consummate scholar, he was a gifted and dedicated teacher and mentor as well. Jeff was also his student, a relationship he shared with many others over the years. There was wide agreement that Tom had a deserved reputation as a fierce intellect who was both a master teacher and quick to cut to core of an argument made in the classroom—whether with praise or critique. He was a gifted teacher who could engage in analysis at the deepest conceptual level while connecting to real clinical cases and policy issues. He crafted watertight arguments that would impress his philosophy colleagues and policy wonks alike.

Impact and awards. Tom’s work garnered widespread recognition and praise in the US and internationally. This recognition includes an honorary doctorate from the University of Tübingen, the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of Bioethics and Humanities, and the Bioethics Founders Award (formerly the Beecher Award) from the Hastings Center, among others.

The practice and virtue of teamwork. Tom excelled at teamwork. So many of his important works are co-authored or co-edited, with a variety of collaborators from different disciplines and perspectives. He was able to exercise his formidable intellect, exceptional leadership skills, and remarkable personal qualities in teamwork, always interacting respectfully, civilly, and graciously with his collaborators and relying on mutual deliberation and justification to chart and implement their joint projects.

We both had the pleasure of working closely with Tom the philosopher and the ethicist/bioethicist in various contexts, but we were also and always relating to Tom the person. All our interactions with Tom were fully integrated, robustly engaged, and sustained in genuine integrity.

We owe much to our relationships with Tom—truly singular experiences for us both, and it would be difficult to overstate his importance in both our lives. Together we count over 100 years of knowing Tom—as his professional colleague and collaborator, as his student, as his co-author, and as his friend. Years of discussing and debating not only bioethics but football, music, and the news of the day. Tom’s opinions were always strong, but always well-reasoned—never argue the merits of Dolly Parton’s musical contributions with one of giants of philosophical bioethics! We loved him dearly and miss him greatly.

Note: The co-authors of this tribute—James (Jim) Childress and Jeffrey (Jeff) Kahn—both worked closely with Tom for decades. Jim was a collaborator and co-author with Tom for close to 50 years on eight editions of Principles of Biomedical Ethics, and Jeff first as Tom’s PhD student over 40 years ago and later as colleague, collaborator, and close friend. We write from these rich experiences and our long-standing friendship with Tom, as well as our deep familiarity with his body of work.

James (Jim) Childress, PhD is University Professor and John Allen Hollingsworth Professor of Ethics Emeritus at the University of Virginia.

Jeffrey (Jeff) Kahn, PhD, MPH is Andreas C. Dracopoulos Director and Levi Professor of Bioethics and Public Policy at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics.