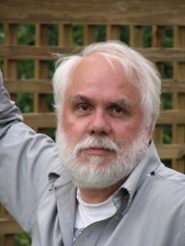

Dr. Andrew Jameton, Professor Emeritus, College of Public Health, University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC); Member, Physicians for Social Responsibility; and Member, Health Professionals for a Healthy Climate (Minnesota), died on November 30, 2022 after a brief struggle with a very aggressive cancer. His wife Marsha, his younger sister Laura, his daughter Rachel, and his close friend Bruce Snyder were with him at the end. He was 79 years old.

Originally from St. Louis, Andy earned his BA in Psychology at Harvard University in 1965 and his PhD in Philosophy at the University of Washington in 1972. He spent the longest part of his distinguished career at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

In bioethics, he is best known for coining the term “Moral Distress” as a way of describing an increasingly common phenomenon in healthcare that, in his view, particularly affected nurses: knowing the right thing to do but being prevented from doing it (Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues, Prentice Hall 1984). To say that this publication took the bioethics world by storm is an understatement. This text formalized not just the philosophical concept of moral distress, but also firmly cemented the nurse’s voice as critical in the bioethics discourse. As recently as 2017, Andy reflected on the role that naming this phenomenon had on the field: he hypothesized that the increase and spread of publications on the concept of moral distress reflected “…an increase in the frequency, intensity, or extent of distress among health professionals” (AMA Journal of Ethics 2017). The solutions are by no means apparent, and for Andy, they related to larger issues about the costs of healthcare, both financial and environmental. He urged us to look to “global social and environmental advocacy” as a way of addressing both issues of moral distress and the ethical challenges of healthcare more generally.

Indeed, by the time I met Andy in 2001, he had shifted his focus from clinical ethics almost exclusively to the philosophy and ethics of environmental health. With the 2003 publication of The Ethics of Environmentally Responsible Health Care (Oxford) with colleague and friend Jessica Pierce, he once again ushered in a new concept for bioethics: the ethical imperative to address the environmental impact of the practice of health care. In Jessica’s words:

“Andy will be remembered and celebrated as one of the leading voices in environmental bioethics, always reminding his colleagues that a commitment to health care rests on a more basic commitment to planetary well-being. Andy was talking about climate change and its relevance to bioethics thirty years ago, before climate change was broadly recognized as a major global threat. He never stopped developing and trying to advocate for this message.”

His last published work, co-authored with Jessica, explored the moral imperatives for those working in bioethics to address “the inevitable forward march of climate change” (doi 10.1353/pbm.2021.0039).

In the 1990s with Virginia Aita, Ph.D., Andy founded a medical humanities interest group for Omaha’s academic community (UNMC, University of Nebraska-Omaha, and Creighton University) which met monthly at members’ houses during the school year, to share a meal and a program. In the 2000s when UNMC initiated an Enhanced Medical Education Track (EMET) to allow students to pursue special interests, Andy and Virginia founded a track in Medical Humanities and mentored students who explored the history of midwifery, the work of physician-authors in the early 20th century, the depiction of medical school experiences in oil and pastel, and many other subjects. This EMET track is thriving today under the tutelage of other capable professors.

With regard to his teaching, colleague and friend Rebecca Rae Anderson, J.D., MS, CGC, remarked:

“Medical students either adored or reviled Jameton; in particular, he challenged their assumptions about people of limited means and education, pressing students to recognize their immense privilege even when they felt penniless and overworked. Not one of them could say that, should an emergency arise, they had no one to turn to for financial or social aid. He remarked that whenever he scheduled a visit to the Howard Drew Center in largely Black North Omaha, a shocking number of students “‘couldn’t find it.'”

One of his former students, the medical humanities scholar Sarah Rodriguez, commented: “Andy was kind, deeply curious, and incredibly generous with his time. When I was his graduate student, I never once doubted his keen and enthusiastic support for my work – indeed, sometimes it was me who had to reign in his ideas for where my dissertation could go rather than the other way around.”

With respect to advocacy: Andy was a co-founder, board member, and long-time advocate for City Sprouts, a community gardening and sustainability education project in Omaha, Nebraska. Now a thriving 501(c)3 organization with multiple locations, a robust urban farming internship program, and city-wide food distribution program, City Sprouts began for Andy in 1995 on a small plot in North Omaha as a labor of love – a way to concretize his commitment to sustainability and to give back to the city that was so good to him. He grew more than vegetables there: he grew compassion, commitment, and love.

The latter was especially true for me personally: my husband and I had what turned out to be our second date working at City Sprouts one afternoon with Andy, building raised beds and preparing the soil for planting. Jessica describes Andy as “one of the gentlest souls I’ve ever known” and as “one of the most imaginative philosophers of our time.” His good friend, Bruce Snyder, commented:

“He was one of the most intelligent and broadly knowledgeable people I have ever met. Our wide-ranging conversations touched on environmental economics; the consequences of climate systems collapse on public health; degrowth economies; the nature of consciousness; the distinct yet entwined properties of empathy and compassion; strategies for climate and environmental advocacy and on and on. He quoted philosophers, poets, writers and playwrights. He played piano and guitar. He enjoyed programming computer games. He tutored his grandson Trace in physics, math, philosophy and chess. He always had a pen and file cards, jotting down thoughts and observations on the fly.”

I remember Andy’s office as awash in chaos of the best kind: full of treasures of thought, practice, and story that represented the brilliant intellect and insatiable curiosity Bruce also referenced. And yet he could focus on you in such a way as to leave no question that he was deeply, honestly, and seriously interested in you and your projects. I could not have asked for a better mentor: he knew when to encourage innovation and when to recommend I set boundaries. He helped me mature into bioethics by embracing my disparate interests and my various commitments. He led by example, by putting his thoughts into action and actively working to make his community, and the world, a better place. I already miss him dearly.

Toby Schonfeld, PhD is the Executive Director of the National Center for Ethics in Health Care at the US Department of Veterans Affairs.