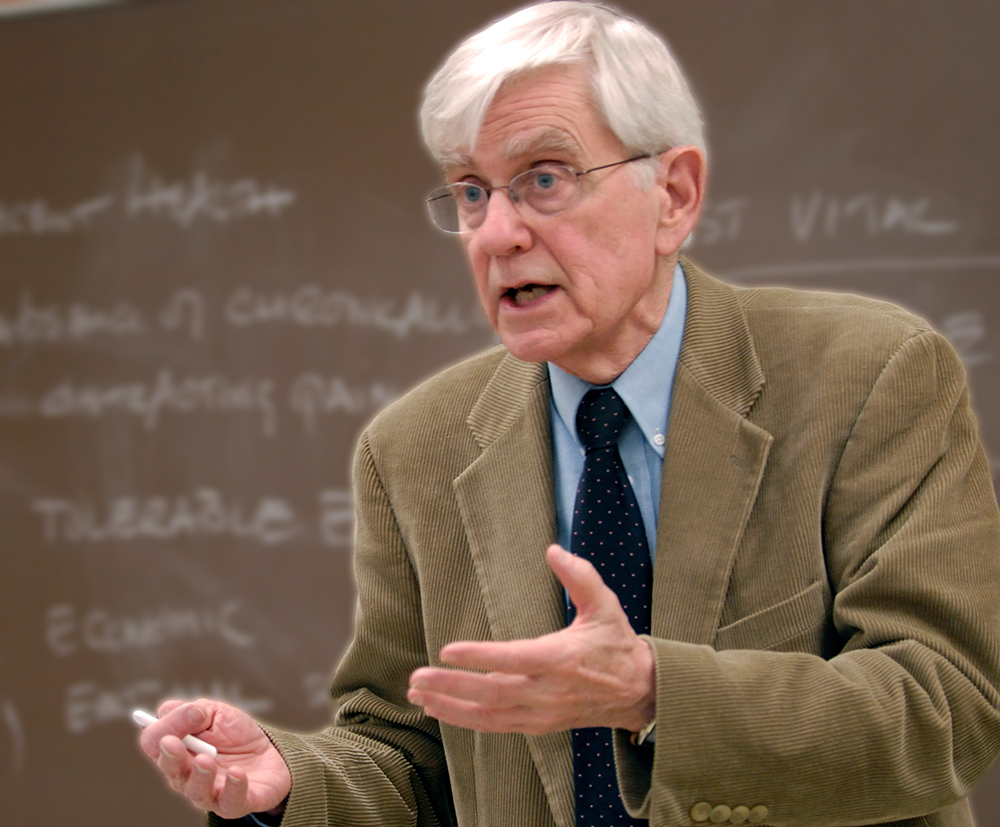

Don Marquis, a philosopher who specialized in bioethics, died on September 13, 2022, at the age of 86. For most of his career, he was on the faculty of the University of Kansas. From 2007-2008, he was the Laurance S. Rockefeller Visiting Professor for Distinguished Teaching at Princeton University.

In terms of his accomplishments as a philosopher, he will likely be best remembered for his work on the morality of abortion. In 1989 he published an article entitled “Why Abortion is Immoral” (The Journal of Philosophy 86(4):183-202). That article has since been reprinted nearly a hundred times. To better understand his essay’s impact, it is helpful to look at his goals in writing it, as he stated in the first paragraph:

“The view that abortion is, with rare exceptions, seriously immoral has received little support in the recent philosophical literature. No doubt most philosophers affiliated with secular institutions of higher education believe that the anti-abortion position is either a symptom of irrational religious dogma or a conclusion generated by seriously confused philosophical argument. The purpose of this essay is to undermine this general belief. This essay sets out an argument that purports to show, as well as any argument in ethics can show, that abortion is, except possibly in rare cases, seriously immoral, that it is in the same moral category as killing an innocent adult human being.”

Two things are particularly noteworthy at the outset. He made it clear that he was making a secular argument. It was probably true in 1989, and perhaps even more so today, that many who argue for the immorality of abortion are in the end relying on religious arguments and perhaps advancing the viewpoint of a particular religion. (Even in terms of the current legal aspects of this issue, no less an authority than Linda Greenhouse recently stated that “religious doctrine, not the constitution, drove the Dobbs decision” overturning Roe vs. Wade.)

But that certainly wasn’t where Don was coming from. Back in the 1980s, Don organized an informal group called the Ethics Club, that has persisted to this day. It met monthly to discuss a topic of interest, with readings assigned ahead of time. People from a variety of backgrounds participated over the years, including philosophers, physicians (particularly oncologists, since life and death issues came up frequently), and even federal judges. From time to time, a new book would come out highlighting one or another problem with organized religion, and a session of Ethics Club might end up being devoted to it. After the meeting, we would get together for dinner at a Macaroni Grill in the Kansas City (Kansas) suburbs. And we would jokingly worry about keeping our voices down during our sometimes spirited discussions, lest someone at a neighboring table hear a too-derogatory comment about religion.

The other important point to note is that Don was liberal – indeed, very liberal. In writing his essay, he certainly wasn’t trying to win friends and influence people, in the usual sense. While in certain conservative circles, there can of course be important career gains to be made from promoting an anti-abortion position, that was the opposite of where Don was coming from. He well knew, as that first paragraph stated, that the position he was taking would be very unpopular within the community of his own colleagues in philosophy. And yet he thought his ideas had merit – that they represented a reasonable and important analysis of the underlying ethical issues – and so he went ahead and published them.

Three decades after his article was published, given what is now happening after Roe was overturned, his ideas are more relevant than ever. One way or another, the U.S. will indeed have to be drawing lines demarcating those circumstances in which abortion will or will not be allowed. The possible role of Don’s line of thinking in that process is demonstrated by the May 20, 2022 episode of the Ezra Klein Show, a New York Times podcast. During that show, Klein interviewed Kate Greasley, an Oxford University law professor who is an expert on the moral philosophy of abortion (though she personally “believes in the right to choose”).

In that interview they discuss, in Klein’s words, “why both progressives and conservatives should be open to questioning their preconceptions about abortion.” As Klein observes, “to be liberal, in modern terms . . . is, more or less, to be pro-choice.” Greasley responds by noting that a “progressive academic” in an institution such as Oxford would be in an “untenable position” if they were not championing reproductive rights.

Having agreed on the important need for all of us – including liberals – to be more open to views that differ from our own, the discussion goes on to examine, in some detail, the various arguments about the morality of abortion. At one point, Klein brings up the fact that “a lot of secular arguments – and I don’t think this is easily dismissed nor do I dismiss it – rely on what you call potentiality principles, the futures we might or that we will have.” Greasley responds that this is “a very interesting argument and one I make all my students read about[.] [P]otentiality is this idea about the wrongness of killing and a future of value. The best person to read on this is a philosopher called Don Marquis, who argues that, as you said, what’s wrong about killing anyone – a person, me, you – is the deprivation of our future, of the future of value.”

And Klein himself – a former Washington Post columnist and editor, subsequently a founder and editor-in-chief of Vox, and at age 38, certainly not part of Don’s generation – at one point makes an observation that well demonstrates the degree to which Don’s ideas have influenced the thinking of at least some young American thought leaders. Klein reveals a sophisticated awareness of not only Don’s ideas, but Don’s responses to critics of those ideas: “So one question that [discussion of the relative merits of saving embryos versus saving a baby] raises to me — and I think this is something that Marquis says in response to some of the claims that his arguments prove too much — is that maybe our moral intuitions are just wrong.”

Don’s work was of course not limited to the topic of abortion. His work on other aspects of bioethics equally well demonstrated his sharp mind. Among those other areas were determining when people are dead for purposes of organ transplantation, and the ethics of research with human beings. Given that these are both areas that I have also worked in, I can comfortably say that his writings in both these areas remain very relevant today. He himself, on his KU webpage, selected these two articles on those topics as “representative” of his publications: “Are DCD Donors Dead?” Hastings Center Report 2010;40(3): 24-31, and “How to Resolve an Ethical Dilemma Concerning Randomized Clinical Trials,” New England Journal of Medicine 1999;341(9):691-696. And in keeping with his liberal viewpoint, he not only taught a course on the “Philosophy of Sex and Love,” he wrote articles such as “What’s Wrong with Adultery?”

Most importantly, Don was a wonderful person. He was a loyal friend, ever curious about the world we live in, almost always upbeat and eager to explore and discuss interesting issues. In the last email I received from him, he was writing about affirmative action, characterizing it as a “great issue” (particularly given the pending Supreme Court case) to discuss at an upcoming Ethics Club session. His death was reported on Daily Nous, a website about the philosophy profession, where the comments were uniformly positive and give a good sense of what type of person he was:

● Alastair Norcross: “[I] always enjoyed his company.” “[H]e was gracious and friendly.” “He had excellent taste in scotch . . .” “Although I disagree with his position on abortion, I always enjoy teaching that article. It is a model of clarity, and pretty much the only anti abortion paper worth taking seriously, at least for those of us unmoved by religious considerations (as was Don).”

● Richard Galvin: “And I too, despite disagreeing with his conclusion, very much enjoy teaching his article on abortion.”

● Christopher Stephens: “He was independent minded, holding less common combinations of views (e.g, atheist, but anti-abortion, in favour of universal health care, opposed to the higher brain definition of death, etc.) I will miss arguing with him.”

● Jason: [Regarding his response to an email from a teacher who was unknown to him:] “Like his paper, the exchange was a great demonstration of how we can do better at such things even when discussing things we disagree strongly about.”

● Deb Heikes: “[He] was the only one of the professors to play on the philosophy department softball team. He was great fun, and he always came out for a beer with us after the games. Great guy.”

● Kaila Draper: “A really nice guy and fun to talk philosophy with.”

One would hope that those in the bioethics community who are not familiar with Don’s work might take his death as an opportunity to change that. Perhaps sit down with a Scotch or beer and watch the video of his discussion with Michael Tooley in 2010 about their respective views on abortion. In a world in which there is no shortage of shouting, and a growing unwillingness of people on both sides of an issue to even consider the views of those who disagree, this is a model of two people with very strong views on an extremely controversial topic nonetheless making a genuine effort to better understand and thoughtfully respond to the views of the other.

Jerry A. Menikoff, MD, JD, is the Director of the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP), a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).