by Joseph Stramondo, PhD

The COVID-19 pandemic reveals systemic health inequities in ways that are hard to ignore. These inequities tracked race, class, and several other overlapping and interlocking oppressions, including ableism. Ableism roughly refers to an ideology that disrespects and unjustly disadvantages disabled people on account of their disability. Ableism can appear in the attitudes and beliefs of individual people or it can be “baked in” to a system of institutions and practices. Systemic ableism was most apparent early on in the pandemic, in the way crisis standards of care were initially drafted that deprioritized disabled people for critical treatment based on problematic notions of quality of life. Medical ableism was again thrust into the spotlight when disabled people who were disproportionately at risk for the COVID-19 infection were not prioritized for vaccination as the roll-out began.

However, it would be a mistake to interpret these instances of inequitable access to healthcare for disabled people as isolated to the specific context of the pandemic. It is widely acknowledged in general that health, or lack thereof, is often determined by social factors and not mere biology. Yet, structural ableism is rarely included as a focal point of the analysis of the social determinants of health. To be sure, ableism is deeply embedded in the structures of medicine, as it is in virtually every aspect of contemporary life. So it is not surprising that disability discrimination can be located in a wide range of medical practices including – but not limited to – organ transplantation, physician assisted dying, prenatal diagnosis and selection, and medical futility policies.

As is the case with any and all systems of oppression, ableism exists as mutually reinforcing, biased institutional structures and individually prejudicial attitudes and beliefs. This is also true in particular when describing how ableism flourishes in the field of medicine. Thus, to combat medical ableism, it’s important to address the ways in which policies create inequity, while also recognizing the role that individual implicit bias plays in maintaining and protecting any such policies. Not surprisingly, implicit bias against disabled people is abundant in the health professions. A recent study in Health Affairs by Iezzoni et al put a finer point on some of these biases. For example, a full 82% of respondents, all physicians, stated that they believed disabled people had a worse quality of life than non-disabled people, a generalization that is as common as it is false. Further, only 40% of physicians surveyed were “very confident” in their ability to provide care of equal quality to both disabled and non-disabled patients. Sadly, only 56.5% “strongly agreed” that they welcomed disabled people as patients at all.

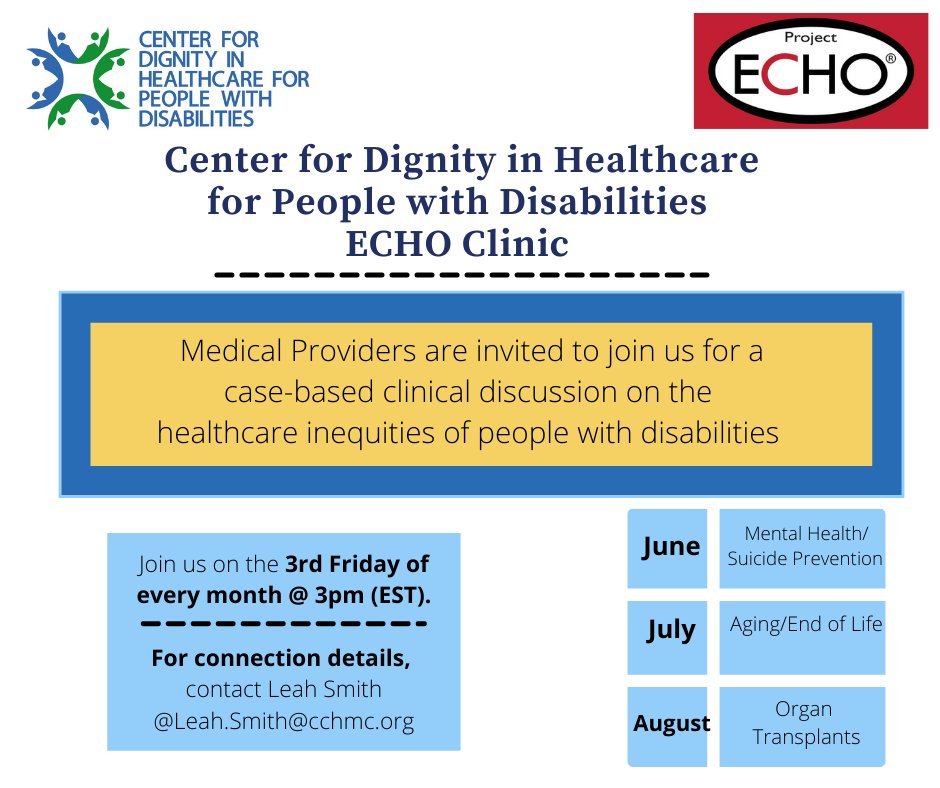

To urgently intervene on these common implicit biases among providers, the Center for Dignity in Healthcare for People with Disabilities has developed a series of case based clinical discussions on healthcare inequities experienced by disabled people. These sessions will occur on the third Friday of every month and will be available via the ECHO platform (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) developed by the University of New Mexico.

The first of these sessions will take place on May 21 and will address inequities in access to mental healthcare and suicide prevention that are experienced by disabled people. It will be lead by Dr. Kaley Roosen, who is a leading expert on a disability affirming approach to therapy.

We must interrupt the feedback loop that exists between structural oppression and individual biases. We can do this by raising the awareness of individual providers to the existence of the structural oppressions that provide the context of their practice.

Healthcare providers who are interested in participating in these sessions can contact the Project Coordinator of the Center for Dignity in Healthcare for People with Disabilities, Leah Smith, for more information: leah.smith@cchmc.org.

Disclosure: The author of this post, Dr. Joseph Stramondo, is married to the Project Coordinator of the Center for Dignity in Healthcare for People with Disabilities, Leah Smith.