by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

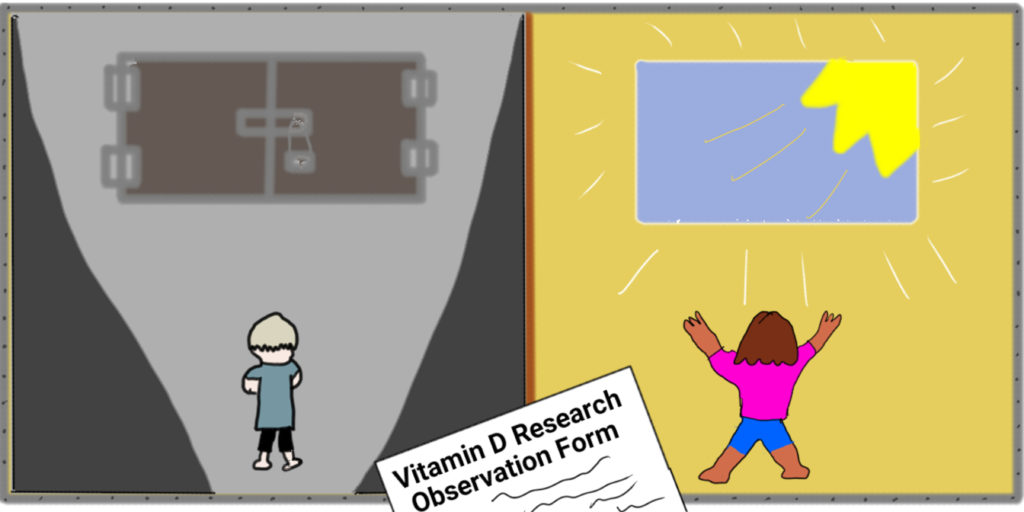

In a 2017 article from India, researchers conducted a meta-analysis looking at vitamin D deficiency and asthma in children. They found a correlation—children with asthma were more likely to have a deficiency—but they did not find a causation—that the deficiency caused asthma, or that asthma caused the deficiency. For example, it’s possible that asthmatic children go outside less because they are more likely to have an asthma attack and thus are less exposed to sunshine, leading to lower levels of Vitamin D. A 2009 article proposed that perhaps adding vitamin D would prevent asthma but without clinical trials, they could not know.

This week, just such a study has been flagged for ethical concerns. Bruce Davidson MD MPH, a Seattle researcher who conducted a similar study last year in Qatar expressed concern about the use of a placebo in the Pittsburgh protocol. When designing his own research, his team decided that a placebo would be unethical: “We did not consider a nonsupplemented (placebo) control group appropriate.” He compared levels and method (IM/oral) of supplementation without a control group.

My review of NIH RePORT and ClinicalTrials.gov showed several NIH grants for this study (total about $2.6 million from 2015-2017) awarded to the University of Pittsburgh. The study recruited subjects at four hospital sites: University of Pittsburgh, St. Louis Children’s, UCSF Benioff’s Children’s and Boston’s Children’s, where the story was initially reported.

According to the University of Pittsburg study’s recruitment website, potential subjects had to be between the ages of 6 and 14, currently on a corticosteroid for their asthma, and with a vitamin D deficiency. Subjects would have 9 research visits over a year: “In the first 5 weeks candidates will have 3 study visits for exams and testing. Those eligible to continue in the study will be randomly selected to receive either a daily dose of vitamin D3 or a placebo to be taken orally for the duration of the study.” The study sought to recruit 400 participants between February 2016 and July 2020. Half of the subjects are given a 4000 IU vitamin D3 supplement and half are given a placebo. All subjects would continue on their asthma corticosteroid treatment. Theoretically, the study should show definitely if raising vitamin d levels leads to a lower rate of asthma.

The main ethical questions this study raises are:

- Would subjects on the placebo would be harmed?

- Would subjects have known about their deficiency if they had not been screened?

- Once a deficiency is known is there an obligation to treat?

- Are children particularly vulnerable to this deficiency?

- Does the study design achieve equipoise?

- Was it safe for the subjects to receive high doses (4,000 IU) instead of a maintenance dose (200-400 IU)?

- Asthma in children targets black children (55% of all cases while they are 14% of the youth population) so how was the issue of vulnerable populations handled?

- Was the risk justified given the lack of efficacy shown in other studies (no randomized placebo-controlled trial in adults has found an effect)?

- A large vitamin company may have been involved with this case: Did they just provide support? Funding? Or did they suggest the treatment protocol?

Vitamin D is important for building strong bones, for muscle movement, for signal conduction in nerves, and for the immune system. Thus, a child with deficient levels would be at risk for rickets, infections, nutritional deficiencies, malabsorption, seizures and may be at later risk for bone disorders and some cancers. It is so important that the professional organizations recommend that all children from infancy take 400 IU per day to prevent deficiency.

Knowing vitamin D’s importance and knowing that the treatment is inexpensive and simple, should the researchers have used a placebo (at least for the year of the protocol)? In a newspaper interview, bioethicist Alan Fleischman MD said using a placebo is permitted under federal regulations: “A placebo trial is ethical when children aren’t being asked to give up something,’ he said. ‘Giving them a placebo “does not increase risk to children who don’t get an active drug’.”

Under autonomy, parents can consent for their children to participate in research after learning the risks, benefits, and alternatives. Researchers are not physicians and thus do not normally have fiduciary duties toward subjects. However, children are vulnerable in that they cannot make choices and in this case, the deficiency can affect their growth and development. Also consider that children with asthma are more likely to be from non-Caucasian racial/ethnic groups and from lower socioeconomic levels.

According to the UCSF consent document, during the protocol, parents and children will not be told if they have a deficiency. Though if the deficiency is very severe (less than 10 ng/ml) or the child is diagnosed with rickets, then they are not eligible for the study and will be referred to a specialist for treatment. If their levels are low after the study, then they will referred to their PCP. In one way, the study provides a benefit in that the children will get a screening and referral they might not have otherwise. But, while the placebo does not put the subjects at additional risk (and thus achieves equipoise), the withholding of timely information may place the subject at risk.

Another aspect of this study that elicits concern is that subjects are asked to give blood for genetic testing and the results will not be revealed to the subject or parent at any time. Why is this necessary since it is not listed in the NIH database descriptions? According to UCSF, “blood for DNA and RNA extraction, to be saved for later genetics testing”. I am not sure how the IRB let this get by, but collecting material that will not be used in the described study should not be taken for future study except under a separate consent for biobanking or future use. It was probably approved because parents may opt out of this testing.

The result of this publicity is that researchers claim they will make changes to inclusion/exclusion criteria and to the consent form. However, consent is not a document, it is a continuing process and it is difficult to provide an understanding of risks and benefits when the research withholds important information about their children for a year (Vitamin D measures) or forever (the genetic information).