by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

In the last few years, the hospital where I serve on the ethics committee has seen a dramatic uptick in the number of patients placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). ECMO is an amazing technology because it can maintain a body even after “severe neurologic impairment or multiorgan failure”. With its ability to replace heart and lung function, a body can be maintained long after the heart, lungs, and even brain have failed.

In ECMO, the machine replaces the lungs (and sometimes the heart). The blood circulates outside the body where it oxygenates and releases carbon dioxide and then returns to the body. This technology can be used when the lung or heart fails. Unlike a ventilator, which requires the lungs to function to be able to transfer gases, ECMO bypasses the lungs. In fact, the technology developed from the heart-lung bypass machinethat made open heart surgery and heart transplants possible. In 1971, Donald Hill, a San Francisco surgeon, used the bypass machine on a dying adult patient suffering from respiratory insufficiency. In 1974, the technique was used on a baby. Although both patients were expected to die, in both cases, they survived. There are two forms of this tool: venoarterial (VA) and venovenous (VV). Both forms are similar in that they oxygenate blood (supplement or replace the lungs) but only VA provides hemodynamic support, i.e. supplements or replaces heart function.

A 2015 study found that the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) had increased by 433% between 2006 and 2011. My hypothesis is that use has increased exponentially since then. The technology is relatively inexpensive, can be rapidly deployed, is portable (within the hospital), is becoming easier to use, and falls under high income billing codes. In the hospital where I serve on the ethics committee, we are seeing more doctors considering ECMO for their patients and more ethics consults for it as well. A 2017 article reports that “Short courses of ECMO may allow critically ill patients to be salvaged, but ultimately survival depends on resolution of the underlying problem or ability to transition to another more durable mode of cardiac support”. ECMO can also be useful to sustain organs for transplant if the patient is a known donor.

Beyond its ability to keep a body going, there are some downsidesto ECMO such as access problems, poor blood flow to extremities, clotting problems, and stroke risks (cerebral hemorrhage). Brain damage is correlated with greater mortality for patients on ECMO.

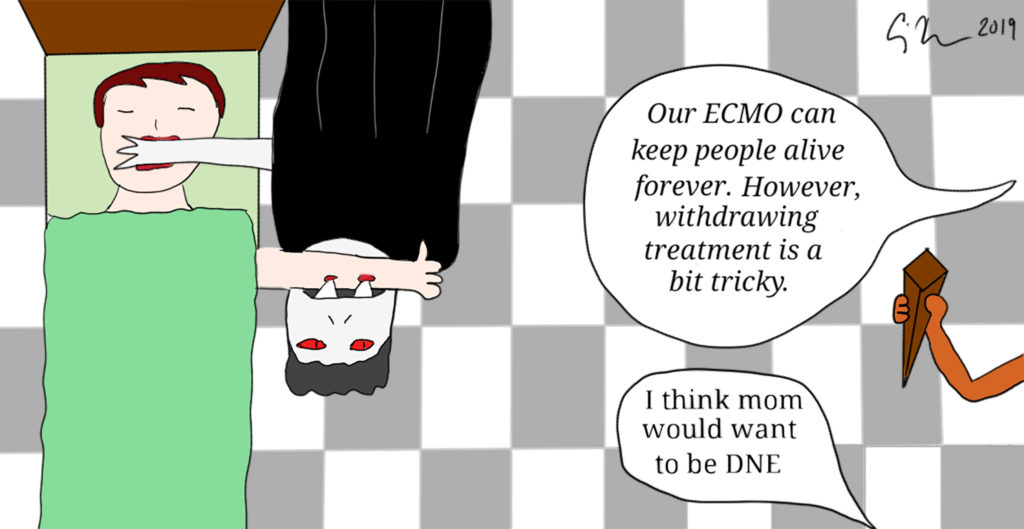

From an ethics standpoint, Kenneth Prager calls ECMO, “a bridge to nowhere.” It is not a destination (unlike a transplant or an LVAD); it is not a measure that can cure a patient, and the longer it is used, the more likely the only outcome will be withdrawal and patient death. Unless the underlying disease can be cured, there is not a road to recovery. Other ethical considerations suggest that patients do not consent to ECMO(unless discussed early in their disease course) because by the time they need it, they are most likely unconscious. Another issue is withdrawal—because ECMO does not require functioning heart, lungs or higher brain function, it can be unclear when to cease treatment: This can cause moral distressfor health care providers facing family members who see, what appears to be, a living body. Another paper found that the ethical issues in ECMO are not much different than they are for any end-of-life body supportive technology.

At the hospital where I serve, the ethics committee is conducting a study on these issues, exploring when it is appropriate to offer ECMO, for how long patients should be on it without showing improvement, what are the indications for withdrawing, and how to educate patients and families about the technology and its ethical use. This work is in its early stages.

If ECMO is not ethically different, then it should be included in advance directives and advance care planning conversations. POLST forms should include an ECMO option alongside resuscitation, ventilation, and nutrition & hydration. We may need to create a new Do Not ECMO (DNE*) order? After all, it is possible that a patient never codes (DNR territory) but ends up on ECMO where they will never code. A DNR order, thus, would not necessarily cover ECMO. A DNE would be a physician’s order and would be a statement that a patient was full ECMO, no ECMO (comfort care only), or temporary ECMO (defined goals or time period). The latter one would require a conversation with patient or surrogate about trying ECMO for a specified period of time and if certain improvements are not seen, that ECMO would be discontinued.

As we develop new body sustaining technologies applicable at the end of life, there is a necessity to develop new orders for new types of treatment statuses, to add new elements for thinking about advance care planning, and to draw new option boxes on our advance directive/POLST forms.

*DNE is a term from Daniel J. Brauner, MD at the Maclean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago