by Barron H. Lerner, M.D., Ph.D.

When an article promoting the idea of medical futility appeared in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 1990, my father was thrilled. He believed the term was an apt description of the end-stage cases he too often saw as an infectious diseases consultant, in which he was expected to prescribe progressively more complicated antibiotic regimens to severely ill patients with no hope of recovery.

The concept of medical futility has achieved mixed success. Advocates have promoted it as a way to discourage aggressive treatment of medical conditions that are not reversible. Critics—and in some instances the courts—have seen it as an unreasonable strategy that interferes with patients’ rights.

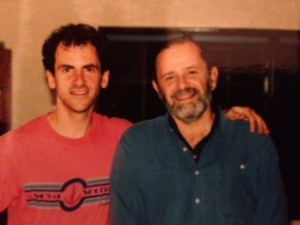

I recently had the opportunity to revisit the concept of medical futility by reading journals that my father kept during his years in practice. His stories remind us of the types of cases that have pushed physicians to try to limit the use of questionable interventions at the end of life. My dad did so as an unabashed paternalist, something that is no longer acceptable. But we should embrace new strategies that seek to achieve this goal in an era of bioethics.

Between the mid-1950s and mid-1970s, when my father first studied and practiced medicine, doctors generally decided when severely ill patients died. They quietly withheld antibiotics, respirators and, ultimately, cardiopulmonary resuscitation. In some instances, these decisions were secretly recorded in patients’ charts.

Trained as a paternalist, my father was comfortable with this approach. But times were changing. By the late 1970s, the concepts of patient autonomy and informed consent, promoted by the new discipline of bioethics, were shifting control of medical decisions to patients. When patients were dying, resuscitation became the default option unless a patient or family member had signed a “Do Not Resuscitate” form.

Although my dad liked aspects of bioethics, he believed that—in the case of dying patients—his hands were being tied. For example, one of his demented patients had both a feeding tube and a tracheostomy, a hole in his windpipe that was connected to a ventilator. Although the patient was “never going to get better or leave a hospital-type setting,” my father wrote, “his family will not accept that reality and continues to pray for a miracle, which will not be forthcoming.”

In another case, an elderly man hospitalized for six months after a hip fracture had experienced countless complications, including infection after infection. “My role in all of this,” my father later ruefully noted, “was to juggle his antibiotics, risk severe toxicities from the multitude of drugs employed and constantly re-adjust and re-dose according to the circumstances.”

In some instances, my father not only objected to aggressive interventions but actively sought to prevent them. For example, he had treated infections for years in a woman with a bone marrow disorder that eventually became leukemia. When she dramatically deteriorated with leukemic cells everywhere, my dad decided not to treat a pneumonia she had developed. Infection, he liked to say, was the “final straw in the deterioration of so many of the body’s vital organs and functions.” The patient died.

Similarly, when a patient with end-stage AIDS developed what my father suspected was lymphoma throughout his spleen, which was causing unbearable pain, he prescribed morphine and did not raise the possibility of treating the cancer either with the patient or his parents.

The most jarring case was one in which my father actually physically placed his body over a recently-deceased patient to prevent his colleagues from performing resuscitation. She had “agonizing” pain and been hospitalized for months and bedbound for years. Resuscitation was inappropriate, he believed, although the patient’s primary physician had not obtained a DNR order.

In one sense, these stories raise the exact concerns raised by critics of medical futility. My dad seemed to be judging for others what was an acceptable quality of life.

But he would have argued that he was using his clinical expertise—combined with what he had learned about his patients’ values and preferences by spending time with them—to make the correct decisions. After all, he was in the hospital seven days a week, gave his sickest patients our home phone number and even managed their cases when we were on vacation.

Thus, after years of keeping his extremely ill AIDS patient alive, my father believed the two of them had a “tacit understanding” about when it was time to let go. After preventing the resuscitation effort, my dad wrote that he had acted “in the name of common, ordinary humanity” and based on his “30+ years as a physician responsible for caring and relieving the pain of my patients who can’t be cured.”

Building on the lessons of the futility movement, modern health professionals are developing more sophisticated strategies for assessing if—and how—aggressive technologies should be offered to severely ill patients. For example, a recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association proposed a framework in which physicians could offer CPR as a plausible option, recommend against it or not offer it at all. Palliative care specialists are not only experts in the scientific value of potential interventions but have the time—as did my father—to get to know patients and families.

These are all positive developments. I suspect my dad, who died in 2012, would also have been pleased. By the end of his career, he was becoming increasingly uncomfortable invoking the paternalistic approach that he had once so devotedly practiced. Ultimately, what mattered most was doing the right thing for dying patients, not who was in charge.