by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Now that you have submitted your taxes, it’s time to consider your death. April 16th is National Health Care Decisions Day, an annual effort to encourage people to think about their end of life care choices and to engage in conversation with others.

In August, I wrote about my attempts in revising and rewriting my end-of-life planning documents including my last will and testament, but mostly focusing on my dissatisfaction with current advance directive forms that require you to make broad choices and really do not speak to who the person is. I talked about my effort to create a narrative advance directive, one that speaks to who I am as a person, what I value in life, and what an acceptable quality of life is for me. In the eight months since that blog post, I have received much feedback from readers and colleagues who offered suggestions on how to make my narrative directive even more useful. Thus, for the 2019 National Health Care Decisions Day, I wanted to share these updates and suggestions.

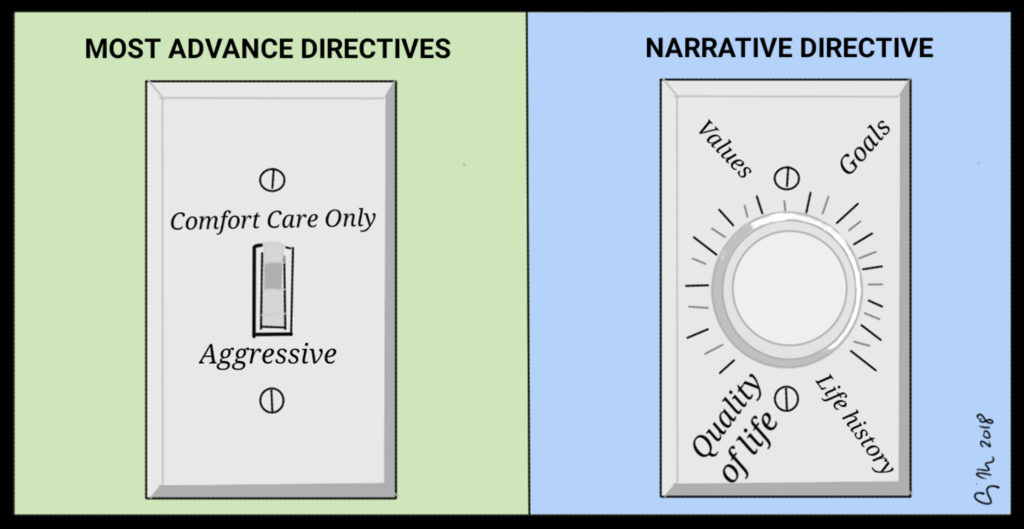

A narrative directive is a document that tells the story of what is important to a person—what makes their life worth living to them. What medical interventions I want is a small portion of it. Over the years of helping providers and families make end of life decisions for loved ones, I learned that the documents that allow for only check boxes (do everything, comfort measures only, do some things but not for too long) are limited in their ability to help in medical decision-making. After all, it is nearly impossible to know exactly the conditions of one’s final days and what the specific medical condition will be. A narrative directive allows a person to tell the story of them, which provides information about values and acceptable quality of life that can help family, proxies, and health care providers to make decisions that align with what the patient feels is important.

As I look back on my narrative directive, I notice that it talks about 8 main points:

- The narrative directive starts with a summary-who are the primary, secondary, and tertiary durable powers of attorney for healthcare.

- The document defines the situationsin which its prescriptions should be followed. In some states, the statute determines when a document comes into effect, often when a person is incapacitated, and has a terminal illness or irreversible condition. Some states, however, do not define the conditions, so it can be important to provide an outline of the situations in which the document should be used.

- Statements of desired treatment goals: These are short statements that offer desired goals of medical treatment in various situations. For example, what is the goal if medical intervention is likely to have little benefit, what about experimental treatments, desire for pain control, any period of conditional treatment (for example, treat more aggressively for 2 weeks or until a prognosis is certain), desires to be supported until family can arrive, and single disease vs. co-morbidity goals. In mine, I included a statement that if I have altered mental status and attempt to negate the document, that those efforts should be ignored because I believe that a person is the integrity of their values over a lifetime, not who they are at any specific moment in time.

- Life and treatment values: What is an acceptable quality of life? What activities form a minimal acceptable quality of life. For example: Is it being able to speak with others and interact? Hike and camp? Watch TV? Spend time with loved ones even if you can’t communicate or recognize them? What conditions or the loss of what activities would lead to an unacceptable quality of life? Do you want to be told that you are dying? Lastly, list the three highest values in your life (in rank order)?

- Spiritual goals: Do you belong to a religion? Do you have beliefs that you would like addressed in your final days? Are there psalms, prayers, poems, music that you want to have with you? Are there any religious requirements (maybe your bed facing a certain direction, or dietary requirements)? Or are you an atheist/freethinker and want your last moments to be free of religion?

- Specific medical care: Here one can offer a variation of the traditional list of what treatments are acceptable under what circumstances. What would you want if in PVS? Coma? Brain death? Unconscious and likely to awaken? How do you feel about antibiotic use (if that would stave off death), dialysis, blood and blood products, respiratory support, surgeries (life prolonging and palliative), artificial nutrition and hydration, CPR? Please note that in many states you must have a specific refusal of ANH and CPR if you wish for those not to be part of your care. The suggestions I have been sent over the last year mostly fall within this category—specific instances of health status that could affect one’s care choices. For example, one reader suggested the document include a statement about hospital and palliative care—is that what one desires? Or refuses? Another reader suggested adding a statement about dementia—what would your care goals be if you had dementia. Other readers suggested adding statements about the acceptability/unacceptability of physician-assisted suicide (assuming one is in a jurisdiction where this is legal) and palliative sedation.

- Additional Thoughts: In this section you can state the kind of setting/environment that you wish to be in when you die. For example, home, hospital, or in-patient hospice? I talked about having a TV on and the kind of stations I would welcome. I also said that I wanted my pets present with me, that no politicians be involved and that my image and case not be used in the media. I also added arogue MPOAstatement—if my power of attorney makes choices inconsistent with this document, then they are relieved of their duties.

- Disposition Thoughts: Although not traditionally part of the advance directive, some versions do include a space for stating one’s wishes regarding body and organ donation, other body disposition, and funeral choices. Perhaps the main argument in favor of including these issues here is that in many states the medical power of attorney has authority over these spheres. Thus, it would be helpful for them to know your wishes.

Be sure to sign your narrative directive and have it witnessed or notarized as per your state’s requirements. If your state requires specific language or has a generally acceptable form, you will want to use that and then attach the narrative directive as an addendum. Perhaps the most important part of completing a directive is to share it with others and use it to have conversations. A document has limited usefulness if no one has a copy and you have not discussed it with them. After all, even if you lay out everything meticulously, your proxy may think what you wrote is not what you meant, and can legally make different decisions. I gave copies to my parents, spouse, medical powers of attorney, attorney, physician, closest hospital, cell phone (under ICE), a wallet card pointing people to an electronic copy in Dropbox, and even as a jpg album on Facebook.

As you teach, acknowledge, and think about end-of-life planning on this Health Care Decision’s Day, remember that the documents are a small part of the process of planning—conversations are essential and a narrative just might help make your values and wishes clearer because those who will make your choices have a better sense of who you are as a person.