by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

It may be hard to believe, but I have been having trouble writing this blog lately. I blame the Supreme Court. My writer’s block began with a series of USSC rulings that were anti-choice, anti-social justice, and anti-fairness. Then came the bombshell that Justice Kennedy was retiring. While he was a conservative on many issues, he was a social moderate on many others such as reproductive choice and civil rights. His work is part of the reason that today my marriage is legal in every state in the union.

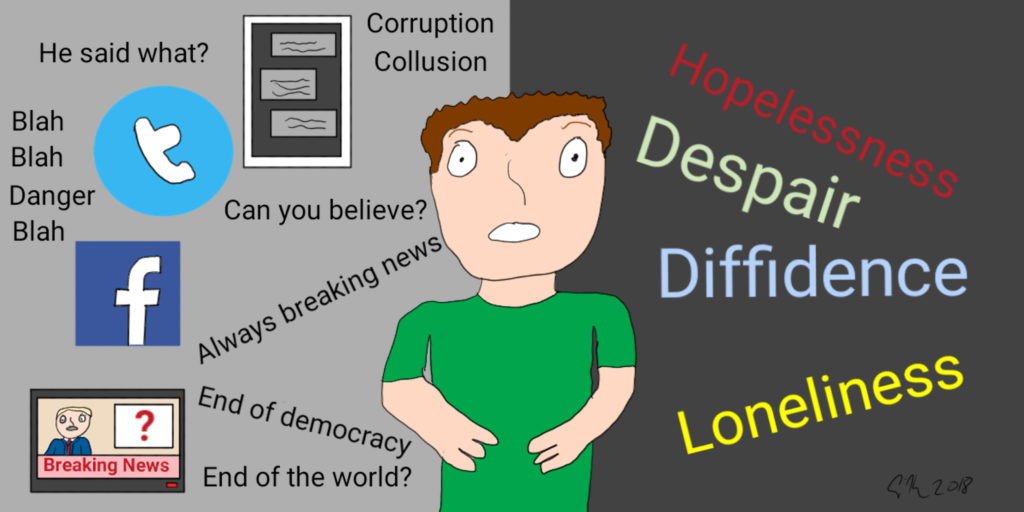

I thought I was alone in having this incessant need to check the news multiple times a day out of fear that I would miss out on something important. With so many tweets and outrageous comments (i.e. “shiny baubles”—diversions) as well as less noticed policy changes (i.e. substantive shifts in government policy), I feel a need to keep an eye on the news ticker constantly. In part, this helps fuel my liberal outrage at the current rightward and autocratic direction the U.S. seems to be heading; in part, I have my elected federal representatives on speed dial so I can weigh in my opinion on issues important to me; and in part I felt a need to keep up to be able to discuss current policy with my students. The more I read and watched, however, the more isolated and scared I became.

Talking to others is a risky proposition today: Will they share my feelings? Will I be outlawed in their minds? Or blocked on their social media feeds? Bioethics practice calls for civility and for treating all positions as valid (even if they are later found to not be), an idea that is core to my work. But, I feel like civility has left the building and was assassinated in the parking lot on its way to its car.

Until Bioethics Summer Retreat. This small gathering of people in bioethics did not make me feel better because they offered a different perspective of the world that alleviated my diffidence. In fact, it seemed that most shared it. And that was the point, most shared my diffidence and my incessant need to keep on top of the news. I was not alone. I am part of a community of scholars and teachers who feel the same need to check their news feeds several times a day, to experience moral outrage (might this be addicting?), and to yearn for greater justice than we are experiencing. We were all trying to keep up and trying to understand how our world has shifted so dramatically and suddenly from one of safety to one where our professional (speaking truth to power, dissecting and making arguments) and personal (religion/non-religion, sexual orientation, gender, ethnicity) personas may make us targets. After all, even if one is not writing a public blog like this one, we all are speaking in the clinic and the classroom to audiences that may disagree with us. Disagreement is a central part of bioethics and leads to communication, sharing of perspectives and values, finding common ground, and seeking shared solutions. One of the important hidden values of bioethics is giving people the tools to make their own decisions: After all, we make recommendations, not prescriptions. In the post-factual world, however, we live under philosophies that see all interactions as a zero-sum game: Either I win or I lose. There is no win-win or lose-lose. Thus disagreement is no longer an opportunity for moral and intellectual growth, but rather is a high stakes game where the outcome could be a loss of face, prestige, reputation, and even position. When discussion is a game that one wins or loses, there is little space for civility.

What is the bioethicist who feels alone and under assault as an academic, an intellectual, and an activist to do? One Retreat attendee relayed a therapist’s suggestion of simply turning off the news or taking in less of it. We all agreed this was unrealistic—we all felt compelled, duty-bound to maintain vigilance of the news. (I actually took a break in writing this at this point to check my news feeds-apparently the US is talking down to our allies, again. Moving on…). What I learned from the many conversations is that I am not alone in my feelings, reactions, or sense of hopelessness. The sense of isolation in dark times is part of the oppressiveness that one feels. Knowing that there are others empowers. Still, there was no answer on how to respond or even how to write about these ideas.

This past weekend, I had guests in town and we visited the Illinois Holocaust Center and Museum. The parallels between today and 1933 when Hitler was legally appointed Chancellor and how quickly that democratic society plunged into fascism is frightening. Consider the road to fascism is paved with: belittling and dismissing the press as an enemy of the state, equating the state with the chief officer rather than institutions, diminishing faith in government, de-emphasizing human rights, obsessing over national security, viewing religion and government as connected, suppressing labor, sexism, disdaining intellectuals, emphasizing law and order, increasing corruption, placing blame for woes on a minority group, and overseeing questionable elections (according to political scientist Laurence Brittand former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright). Fascism thrives on secrets, division, and propaganda. People are encouraged not to question but to trust in a supreme, strong authority figure (rather than in institutions or themselves) and to follow blindly, unquestioningly.

However, in a special exhibit, was an homage to the 75thanniversary of the Warsaw uprising when Jews in the ghetto, knowing they were going to be killed, rose up and managed to cause trouble for their oppressors. Ultimately they lost and most were killed, but they stood up and fought. They spoke their truth and defended their democratic ideals. I learned that even in the most inhumane conditions we must survive, we must tell stories, and we must continue to fight for freedom, tolerance, and our right to live.

I also saw a play, Guards at the Taj about the nature of beauty and its role in society as well as about cruelty, loyalty, and carrying through the orders of authority figures even when we know those orders are wrong. The play has two characters, the guards in the title, who are tasked with chopping off the hands of the 20,000 artisans who built the Taj Mahal. The emperor wants to be sure that nothing more beautiful than this shrine will ever be created. The guards barely question these orders or its effects until they have removed and cauterized 40,000 hands. Both are rewarded for their efficiency. When one of the guards questions a monarch who would require such an action, his fellow guard and best friend is ordered to chop off his hands as punishment for sedition. The play opens the question that has been in my mind: The immoral work of a despot can only exist if there are people willing to carry it out.

Through experiencing art, exploring history, and talking with others, I am regaining my voice and breaking through my writer’s block. The worst thing we can do is go into hiding, to find jobs in other countries that are more democratic, or to refrain from speaking out because we do not want to offend anyone’s sensibilities. What we can do is what we have done all along: Teach, write, advocate. I am going to bring voter registration forms to all of my classes; I am going to give extra credit to my students who vote in the November elections (I won’t tell them how to vote. And if they cannot vote, they can write a short essay on a related topic for the same credit). I am going to keep calling my Senators and Congresspeople and working to inform others (i.e. be a thought leader) about the news they may be seeing and laying out the implications for what is happening in our country. We are only as great as the freedom, opportunity, and justice that we demand for all people in our society. We overcome writer’s block, diffidence, and hopelessness through art, through history, and through careful analysis.