by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Like many Americans and Canadians, I hold in my hand a ticket for a chance to win to the record $1.5 billion lottery. For a couple of bucks, you can dream: My spouse and I talked about being able to pay off student loans, buy a new house, maybe buy a vineyard in France. The media write articles on the long lines, the high hopes, and how this money will help fund schools and public programs.

My question is why is the idea of winning huge amounts money so attractive that it encourages people in droves to spend their money on a 1 in 292 million chance of winning big? After all, the odds of winning are awful. Your chances of being hit by lightning in any year is 1 in 700,000 and over your lifetime is 1 in 3,000. Odds of being attacked by a shark is 1 in 11.5 million. Chances of being struck by a meteorite are 1 in 250,000. Odds of becoming President of the U.S. are 1 in 10 million. The only odds more remote than winning the jackpot is being struck by re-entering space debris at 1 in 100 billion.

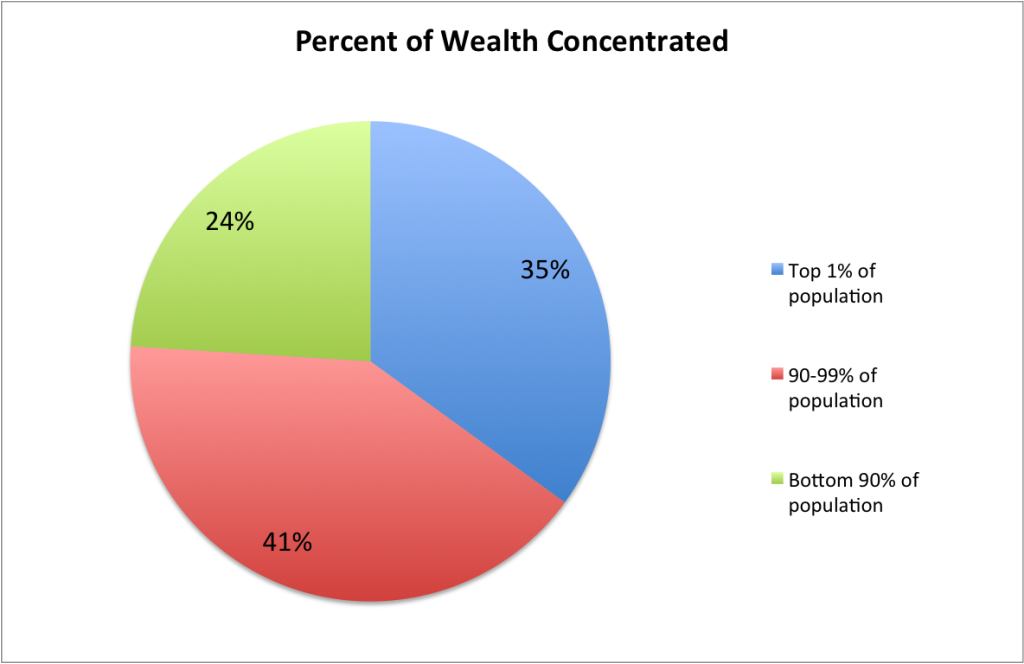

The answer is that we live in a society of great and increasing wealth inequality. I’ve written about income inequality where the top ten percent of earners bring home about 28 percent of all income and CEOs make 300 times their workers. But wealth is the value of all of one’s assets. This is not just income, but also your homes, investments, and more. On that basis, 10 percent of U.S. households have 76 percent of all wealth in the U.S. and the top 1% control 35% of all wealth. Wealth is more challenging from a societal level because once accumulated in a family it tends to stay in that family.

This also means that 90% of people in the U.S. are left with only 24% of all wealth in the U.S to divide. When you realize that your income is low, its buying power is shrinking, and your chances for upward socioeconomic mobility are close to nil and add on top of that the idea that the majority of wealth in this country isn’t even available to most people to dream of accessing, well then, the lottery looks good. And so we go out and by tickets.

Lottery money goes not only to the winners, but 5% also goes to the store where the ticket was purchased. Money pays for the administrative structure of the lottery. Depending on the state determines where the rest goes. In some states that is general revenue, in others environmental protection, school aid, parks and recreation, police and firefighter pensions, college scholarships, assistance to the elderly, or crime control. The downside is that when lottery money pays for these things, state legislatures tend to allocate less money from the general budget. The net result is no change in funding for these priorities.

The lottery is a regressive tax that is born on the backs of the poor and uneducated. More tickets are sold in the poorest counties. Those of lower socio-economics and lower educational attainment are more likely to play and to play more regularly. Minorities are also more likely to spend more.

We buy these tickets because there is an inherent unfairness to our economic system. The Horatio Algiers stories today are rare and for the most part, things of the past. We live in a society that coerces us to always want more, and we think that more money will lead to more happiness (the wealthy are less sad, but are no happier). We also live in a society where not only can’t we have all of the things that we think we want, we often can’t have the things that we need like shelter, food, and healthcare. 14.5 percent of Americans, or 45 million people, live below the poverty line. If that doesn’t seem like much, consider that the poverty line is $11,770 for individuals and $24,250 for a family of poor. 64% of all Americans make less than 400% of the poverty line (a measure often used for means-testing): $46,800 for an individual or $97,000 for a family of four. Also note that income is directly related to health: the wealthier live longer and live in better health.

Consider that for last week’s $947.50 million jackpot (that no one won), $440,321,172 in sales took place. At $2 a piece, that’s 22,016,058 tickets sold. For money that people willingly (or coerced given the marketing campaigns and power of dreams of wealth) parted with, what could we as a nation do with $440 million a week? What could people do for themselves if they kept that money!

Outside of the large jackpots, the lottery is regressive, relying on those who have the least to stay afloat and to fund services that should be paid through our government, which is funded by taxes on a progressive system—meaning that those with more, pay more. While you watch your numbers and hope for that big win, remember that while the $2 you spent may mean a small instead of a large coffee, for the person behind you in the ticket line, that $2 may have meant skipping, not being able to afford a medication co-pay, or turning off the heat.