by Bandy X. Lee, MD, MDiv

A novel coronavirus strain has rapidly spread around the world into a pandemic. Country responses over the past several weeks show that information dissemination is crucial for containing the disease. Psychological readiness to accept intelligence reports, public health advice, and the reality of the disease itself therefore is critical to a nation’s concerted behavioral change. But what happens when that psychological readiness itself is lost?

Through no fault of those receiving misinformation, falsehoods can spread rapidly through our interconnected, social media-driven society. At its extreme, the acceptance of misinformation can morph into a delusion, as we all seek answers during a vulnerable time. The conditions for “Induced delusions” include the presence of an influential source—a public figure, a sensational pundit, or a social media influencer—who is suffering from actual delusions and in whom the audience has great emotional investment. When enough people are bonded to the same figure and therefore share the same delusions, the situation can quickly balloon into mass hysteria. Recognizing and reducing the contagion of delusions is critical to improving our ability to deal with a viral pandemic.

Induced delusional disorder (also called “shared psychosis” or “folie à deux, trois, quatre, millions,… depending on the number involved), or mass hysteria when affecting a whole population, is an often dramatic yet easy-to-miss phenomenon that involves induction of symptoms, usually delusions, from person to person. In the psychiatric setting, it typically occurs when otherwise normal persons have prolonged exposure to a severely impaired individual who goes untreated. These previously healthy persons succumb to similar symptoms as if they had the primary illness themselves, like an infection; delusions of persecution or general paranoia are the most common, but even bizarre beliefs, such as the primary person being of divine origin, are not rare. And since emotions are the driving force behind this contagion, the influence of delusional ideas can be stronger than that of strategic lies, as the primary person truly believes them.

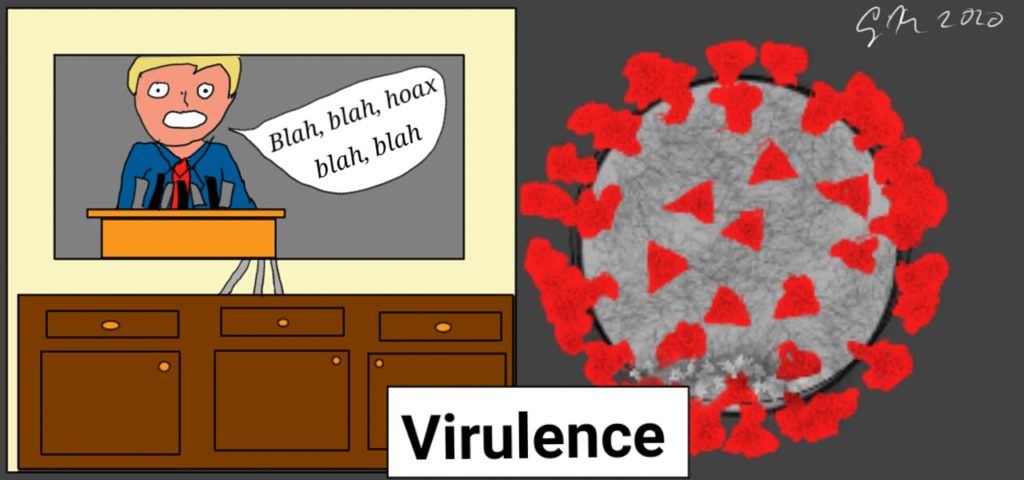

For example, if an influential figure holds or claims to hold the belief that a serious viral pandemic is a “hoax”, orchestrated by one’s enemies to bring down one’s presidency, healthy individuals may adopt that belief through repeated, compellingly-delivered exposures.

As a forensic psychiatrist who consults on policy and public health approaches to violence prevention, I, along with my colleagues at the World Health Organization, have often conceptualized violent behavior as a contagious disease. Through my work in prisons and public hospitals I have also witnessed first-hand the spread of mental symptoms by contagion. Far from being a fantastical idea, the transmission of mental symptoms is well-documented and widespread, especially in crowded, institutional settings. It can also become more rapidly widespread and more serious than ordinary infectious disease, since its vector is emotional bonds, not physical contact. And it is more serious because what is hijacked is the mind—the very vehicle that is capable of recognizing what is wrong.

I am not saying that those accepting one claim or another about COVID-19 are mentally ill, but that induced delusions can be dangerously contagious, if only for the duration that they are exposed to the primary source. The current crisis should serve as a warning that the spread of misinformation should not be taken lightly, and delusions have the additional complication of resisting correction. While the daily bombardment of false information from propaganda and conspiracy-theory sources can mislead the population, even more serious is the emotional attachment to false beliefs that may ”immunize” against facts and information that are critical to survival.

The seductive and hypnotic effects of political or other popular figures, especially when suffering from actual paranoid beliefs, for example, can result in the rejection of legitimate sources of information. For example, when the President announced that the malaria medication chloroquine had been FDA-approved to treat the novel coronavirus, the FDA Commissioner had to walk back the remarks immediately, stating that clinical trials were necessary. However, those who are emotionally attached to the president will cling to their affirmed wishful beliefs, and it appears now that it was deemed preferable for the FDA to grant emergency approval to prevent massive discord rather than because of any evidence that the benefits outweigh the risks.

What, then, is important to know about induced delusional disorder, or mass hysteria, during a global pandemic? When correct information and accompanying behavioral change can mean the difference of life and death, we must consider not only the information that is conveyed but potential emotional barriers to its receptivity. Simply supplanting falsehoods with correct information, especially when the carriers of the falsehoods are influential people, is insufficient. Hearing, “We have it totally under control,” or “One day, it’s like a miracle, it will disappear,” can generate high emotional investment and attachment to the source, especially when correct information is more ominous.

Prevention is highly effective, and awareness of the phenomenon of induced delusions is critical for early detection and intervention. Health professionals can be mindful of the emotional investment that can accompany false beliefs and be empathic about the difficulties that a transition to reality can entail. If induced delusions have been longstanding, individuals may have developed additional layers of protection, such as idealization of the source of misinformation, or reflexive resistance against facts, especially in a time of uncertainty and fear. Reaching out to them with empathy and offering reassurances of a safe place in reality through understanding and human care, can go a long way in reversing some of those effects. An informed and grounded public will strengthen our collective mental health as well as enhance our ability to tackle public health crises.