The following editorial can be found int he March 2024 issue of The American Journal of Bioethics.

Introduction

Dr. Galasso’s insightful article expands the ongoing debate on the utility and equity of precision medicine in public and population health. The initiatives mentioned, Genomics England and the All of Us Research Program, have been at the forefront of large-scale genomics projects across the world. Thus, an analysis of the Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues of these programs can serve as a helpful blueprint as future programs are conceived, constructed, and launched.

While these efforts have made strides in advancing our understanding of genomics and its relationship to the social determinants of health, there is widespread consensus that the benefits must be distributed equitably—or gaps in health and health care can widen.

Dr. Galasso outlines upstream exclusionary factors and divides them into objective (practical impediments such as single language consents or the need for technology to enroll in research studies) and subjective (having the capacity to enroll but electing not to do so due to mistrust in the research process, fear of data misuse or discrimination).

She also describes a larger issue of downstream exclusion, when interventions resulting from precision medicine initiatives are not accessible due to issues such as cost and access. While both upstream and downstream issues deserve examination, they won’t be solved by a single approach.

The All of Us Research Program

The scope of the Genomics England and the All of Us Research Program share the ambitious goals of transforming healthcare, accelerating research, and improving health for the citizens of their respective countries. This paper’s response focuses on how All of Us addresses upstream and downstream exclusion and lays the groundwork for a more equitable healthcare landscape in the U.S. Healthcare System.

In considering objective barriers, for example, All of Us has prioritized a variety of tactics such as eliciting informed consent through video as well as in English and Spanish text, employing bilingual recruiters, and building and supporting a fleet of mobile vehicles that can bring the program to communities that may not be near an enrollment center or where there are digital access issues.

Developing an Equitable Research Platform (Upstream Approaches)

Importantly, the All of Us Research Program is a platform that enables equitable precision medicine research, including population and public health research. As the largest and most diverse publicly available data set that includes genomic sequencing paired with electronic health records and survey and geocoded data to capture social determinants of health and environmental exposures, it is a rich opportunity for investigators to conduct and advance research relevant to the diverse communities who chose to participate. The database currently contains 745,000 participants (on the way to one million or more), ∼45% of those being racial and ethnic minorities and 80% plus underrepresented in biomedical research (including sexual and gender minorities, rural populations, etc.). All of Us has strict data use agreements to protect the data, does not allow stigmatizing research, and requires increasing levels of training and security associated with increasing access to data. The open-access nature of the All of Us dataset contributes to the democratization of knowledge through a tiered point-of-entry system. At the public level, All of Us enables citizen and community scientists to use the de-identified aggregated data to explore health conditions. Access to genomics and more granular data is achieved through a securely protected ecosystem, allowing scientists to collaborate across institutions in a standardized language, overcoming a bias of access to data that has existed in other large-scale efforts. All of Us purposefully recruits researchers from groups under-represented in the biomedical workforce, such as sponsoring an LGBTQ + Basecamp for researchers through a collaboration with the PRIDEnet study at Stanford University (M. Lunn, PI) and working with Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Hispanic Serving Institutions and City and State Public Institutions to encourage a diversity of researchers and research topics.

Downstream Challenges and Benefits

While we have progressed in addressing some of the upstream determinants, the greater challenge is equity downstream. To provide concrete approaches, we begin with examples from All of Us that have enabled collaboration among researchers, health systems and community-based organizations. We finish with a challenge to our healthcare payers and federal and state agencies.

Community Partnerships

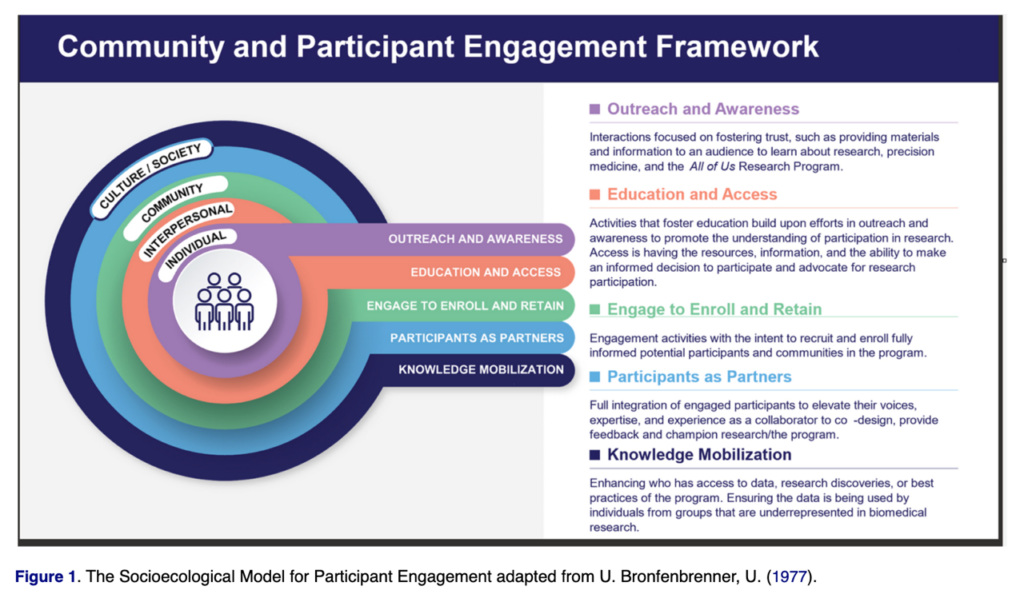

Engagement of individuals and communities that have been historically underrepresented in research is a priority for the All of Us Research Program and central to achieving its bold goal of building a participant community of a million or more that is reflective of the diversity of our country. The program created a Chief Engagement Officer in its leadership team, and in this role, Dr. Karriem Watson and his Division of Engagement and Outreach (DEO) team developed a socio-ecological model that guides the engagement approaches by both the program and the extensive network of community partners in addressing upstream barriers and downstream concerns (Figure 1).

Dr. Watson and his team oversee a network of 17 national engagement awardees that support local and national partnerships—including populations historically underrepresented in research—across the country. As one of the national engagement awardees, Pyxis Partners (R. Tepp, PI) has built and supports a network of over 100 community partners that work to localize this national program and engage potential participants from communities historically underrepresented in research through trusted messengers. This network includes healthcare provider organizations, social service organizations, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Minority Serving Institutions, Black Greek organizations and faith-based organizations to address many of the subjective barriers. This commitment by the program to engage trusted voices has been central to the engagement work supported by the program, as evidenced by its launch in 2018 from Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, the first African American church in New York State.

In addition, contributing to the operational functions of the program, the All of Us Participant Ambassadors, led by Dr. Consuelo Wilkins, have participant representation on each standing committee and all leadership committees of the program to continue to raise the voice of program participants at the highest levels.

Returning Value to the Community

Foundational to All of Us is a set of core principles, including the return of value to the community. We build on Galasso’s model by positing that value is not limited to the ability to identify precision therapies. In addition to pharmacogenomics and targeted therapies, value can be achieved by collaborating with communities to address conditions identified in the data–and linking people to screening and care.

The Tailored Outreach for Uniting Community Health (TOUCH) Health Fair is an example of addressing downstream conditions. Under an affiliated grant mechanism funded by the DEO, the Interdisciplinary Guided Network for Investigation, Translation, and Equity (IGNITE; Cohn, PI) uses the All of Us data set combined with community-level data to identify the top three health conditions in a community. IGNITE then partners with local churches and community organizations to host a four-part tailored health fair consisting of (1) identifying the top three community concerns, (2) providing educational materials tailored to the health conditions identified, (3) where available and appropriate, arranging for point-of-care testing for those conditions, and (4) linking community members to local services. In this way, the community sees research in action, and we can begin to provide a downstream benefit.

The second IGNITE model is the Building Upstream Infrastructure for Learning and Dissemination (BUILD grant) awards. These grants are competitively awarded to community-based organizations and range from $25,000 to $100,000 to guide work that enhances the health of communities based on the All of Us data set. This year’s projects include a training for Community Health Workers for the use of the data set with Spanish-speaking community leaders and community members, and a Wellness Clinic in New York City Public Housing informed by the All of Us data findings.

Pyxis Partners has collaborated with the All of Us Division of Outreach and Engagement, program partners and local community members to design and implement events to educate people about participation in research, discuss historical transgressions, share what new knowledge is being gained about specific communities through exploration of the All of Us data and answer questions. Local advisory committees are formed and supported to shape the discussion specific to their community and to identify appropriate messengers. These local convenings represent another way that the program is returning value to communities.

Lastly, while the return of genomic information to All of Us participants could be considered a benefit, it also created a challenge as some participants who receive actionable information may not have access to a healthcare provider. To address this challenge through a participant-centric model, the program arranged for a network of genetic counselors, supported through Color Health, to help participants—at no cost—understand what the genomic testing results mean for their health and their families.

Opportunities Remain Open for Public and Population Health

Researchers and community advocates have long been deeply concerned by the social issues that plague our nation: poverty; lack of access to health care; lack of insurance coverage; unequal educational and employment opportunities; wage differentials; housing issues; poor transportation options; and systemic and structural racism. These injustices and structural challenges won’t be solved by precision medicine or, indeed, by most types of research endeavors. They should, however, be incorporated as part of any effort attempting to improve the nation’s public health. Many of these efforts are downstream and outside the direct influence of a program like All of Us. However, by generating evidence, returning value, and providing empowering data directly to participants, we are hopeful that All of Us can move us toward upstream solutions and downstream progress.

Comprehensive work such as this often reveals unmet medical and social needs. Dedicated community researchers and advocates often spend a great deal of time on the “shadow work” of linking people to services and providing references, referrals, and support. Collecting information on a population with unmet needs, and recording the data, but proceeding without an attempt to relieve the conditions does not improve people’s health, and understandably, continues to harm the research enterprise. Because the National Institutes of Health is a research institute, they should continue to address upstream factors, as they have done with women’s health research, the Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities, the NIH Community Engagement Alliance from the National Health, Lung and Blood Institute (CEAL) and the Common Fund Community Partnerships to Advance Science for Society (ComPASS).

We further suggest that the downstream solution must also involve the participation of federal agencies and local social service organizations to ensure there is a path to a seamless transition from research to clinical to community care. Recently issued by the White House, The Biden-Harris U.S. Playbook to Address the Social Determinants of Health suggests such linkages in meeting health-related social needs in clinical care. As medical and social needs are identified through research, they should be paired with services. If linking patients to services is going to be done by working with community-based organizations as has been proposed, it will require capacity-building and collaborative planning. Many community organizations operate on a shoestring and cannot increase services and volume without additional funding and personnel as would be necessary to meet the increased demand.

Lastly, addressing the systemic and structural issues will require a shift in the research paradigm. If we are serious about improving our nation’s health, we must promote civic engagement and advocate for policies and practices that correct those injustices and issues.

To this end, Healthy People 2030 has added Civic Participation as a core research indicator and an individual and community metric toward better health. Participation in our communities by researchers and health providers is a way to begin to address the downstream factors. Organizations like Vot-ER which develops nonpartisan civic engagement tools and programs, can help medical professionals and researchers take action for healthier communities. Vot-ER badges and toolkits are used in over 600 hospitals and healthcare systems. These toolkit and voter registration badges encourage participation in our civic health as a pathway to better community health. This is an important next step.

Over the last three decades, health equity scientists have worked to solve the upstream issues. We applaud Dr. Galasso’s efforts and join the ELSI community in considering how to address the downstream issues of access, affordability, and acceptability to achieve our goal of a healthier nation for all.

Funding

Dr. Cohn is supported by the National Institutes of Health for the Interdisciplinary Guided Network for Investigation, Translation and Equity IGNITE (OT2) OD031915. Ms. Tepp is supported by the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program Engagement and Retention Innovators (OT2) OD028404.

Elizabeth Cohn and Ronnie Tepp