Along with apple pie, colonialism, and imperialism, one of America’s best-known characteristics known around the globe is its “war on drugs.” Although many other countries had and are still having their own violent and oppressive wars with drugs, and specifically people who use drugs, America is unique in that its war on drugs included domestic and foreign interventions and at least a trillion dollars.

Given the backdrop of America’s racist and classist war on drugs, including the highly politicized “crack epidemic” and “opioid crisis,” how ought bioethicists to think about psychedelics—therapeutic and non-therapeutic uses—within this context? Psychedelics discourse within bioethics, philosophy, public health, law, anthropology, Indigenous studies and other disciplines is growing around the world and there are lessons to be learned from America’s criminalization and stigmatization of drug use. In particular, for Western and/or privileged academics, responsible discourse and advocacy on behalf of psychedelics research, clinical trials, and use must be done within the inescapable long-term effects of America’s war on drugs and its war on poor, Black, and Latino people.

Brief History of America’s “War on Drugs”

Nixon

President Nixon officially declared a “war on drugs” in 1971. In support of his supposed goal to rid the US of drug use and stop the flow of drugs coming into the US from other countries, a few years into his presidency he also initiated the creation of the Drug Enforcement Agency. There is solid evidence, including an admission from a government official, John Ehrlichman, Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs under Nixon that the “war on drugs” had other motives, including criminalizing and disrupting Black communities:

“You want to know what this [war on drugs] was really all about? The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying?

We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news.

Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Reagan

In the 1980s, President Reagan initiated mandatory federal sentences of a minimum 20 years to life in prison for violating certain drug laws. These laws also came with harsher punishment for the offense of possession of crack compared to the possession of cocaine. This is significant because the majority of people who used crack were people with lower incomes and Black and Latino people, meaning more Black and Latino people and poor people were imprisoned for longer amounts of time because of their drug use. This also meant the long-term effects of having a criminal record such as not being able to vote, and difficulties securing jobs and housing were also disproportionate among Black, Latino, and poor people. Reagan also spent over 1 billion dollars on the war on drugs, which was mostly spent on law enforcement and international military operations in places like Panama and Columbia.

First Lady Nancy Reagan also began the popular social campaign “D.A.R.E. to say no to drugs” where we get the once very popular saying “Just say no to drugs.”

Bush Sr

In the 1990s, during the President George W Bush years there was an additional branch added to the “war on drugs.” The tactic was to make using drugs shameful; to make people look down upon and ostracize people who use drugs. While the domestic tactic was to ostracize drug users, international military efforts were still in effect. Bush would go on to spend $45 billion dollars on the war on drugs, more than the previous four administrations combined, and most of it was on law enforcement.

During this time, public attention to the “crack epidemic,” largely fueled and over-exaggerated by the media was a prominent part of the “war on drugs.” Thin so-called “crack babies” appeared on the cover of newspapers and magazines, Black women were called “crack moms” and often talked into sterilization as to not birth anymore “crack babies.” The “crack epidemic” reflected and fed into the classism and racism that had long permeated America’s treatment of drugs and people who consumed drugs.

Bush Jr

The second President Bush could be heard on the radio in 2008 declaring the “war on drugs” a success. He also praised Columbian president for “standing tall” against drug traffickers. He continued the trend of sending large amounts of money to other countries to aid their own “war on drugs.”

Clinton

In 1994 President Clinton passed the largest crime bill in US history, which mostly allocated funding for more police officers and more prisons. Again, billions of dollars were given to other countries to help fight the “war on drugs.”

During Clinton’s presidency the US sentencing commission released a report that provided factual evidence that there were great racial disparities in who was imprisoned for cocaine versus crack cocaine given President Reagan’s initiation of minimum prison sentencing. Yet, for the first time in history, Congress overrode the US sentencing commission’s recommendation to find ways end to the discrepancy.

After almost twenty years later, during an interview for a documentary about the “war on drugs” Clinton declared the “war on drugs” a bust:

“Well obviously, if the expected result was that we would eliminate serious drug use in America and eliminate the narcotrafficking networks — it hasn’t worked.”

War on Drugs Failed, so What Does This Mean For Psychedelics?

Since 1971, America has spent 1 trillion dollars on the “war on drugs” just for the drugs to win. Rather than funding social programs, significantly raising the minimum wage rate, making housing affordable, giving us universal healthcare, all of which could have provided the resources people needed to live more stable, healthy lives, we got a war on drugs that failed Americans. But it did put a lot of poor, Black, and Latino people in prison, often for small drug offenses, criminalize being poor or having substance use disorders, make Black people not trust law enforcement and destroy families. So if that was the goal, and arguably it was, then it succeeded. The war on drugs also stigmatized consuming drugs in general, making even therapeutic, spiritual, or “recreational” use of drugs greatly looked down upon.

So what are the lessons researchers, clinicians, ethicists, advocates and others who are working with psychedelics can take from the “war on drugs?”

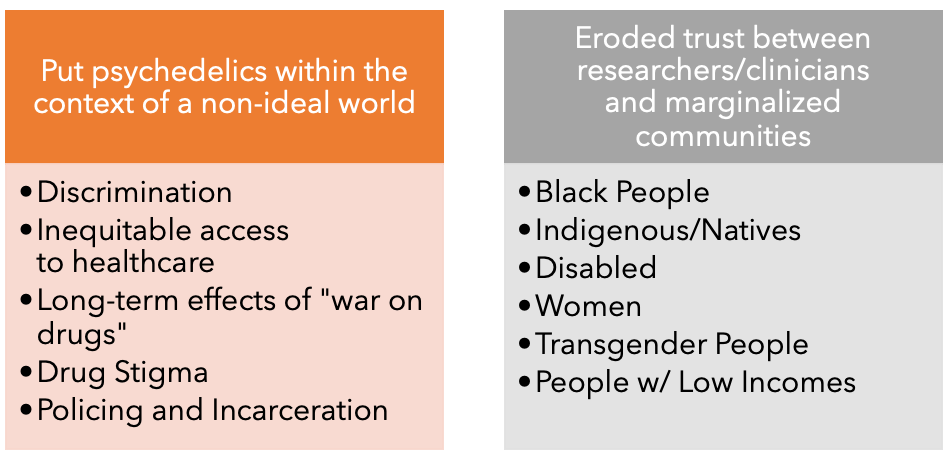

1. We live in a non-ideal world. It’s discriminatory, violent, oppressive, and unjust. And non-ideal theory requires us to acknowledge the shortcomings of our social society and think about our actions and behaviors within this non-ideal context. In particular, some people suffer more social, political, legal, and economic losses within non-ideal worlds.

2. We can’t ignore that psychedelic work is operating within the context of the “war on drugs.” This means that some people may be hesitant to participate in clinical trials for fear of legal punishment, stigma, losing their jobs or having their children removed from their home by child protective services.

3. The violence of the “war on drugs” coupled with America and other countries’ historically (and contemporary) oppressive relationship with intentionally marginalized groups like Indigenous/Native people, Black people, disabled people, people with low incomes and other groups means that we have to think about how our work has the potential to further marginalize already marginalized people.

4. Many institutions do not have great relationships with the aforementioned groups, including scientific research, therapeutic research, health care, and legal systems. (see chart below)

Below is a non-exhaustive list of the kinds of questions we should ask ourselves as we work on the topic of psychedelics:

The war on drugs ultimately was a policy failure, an attack on people who consume drugs and on Black, Latino, and poor people; but it is a prominent feature of our non-ideal world. And as we move forward with our work with psychedelics, we cannot ignore the “war on drugs” elephant in the room.

Keisha Ray, PhD is an Associate Professor at McGovern Medical School, McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics at UT Health Houston.