by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Move over United States, China is the new research powerhouse. In the last few months, announcements out of China talk about the first live human births from genetically edited embryos; the birth of 5 cloned, genetically edited monkeys, and most recently, announced the development of an artificial intelligencethat is more accurate than human doctors at diagnosing diseases in children. Why this sudden surge in Chinese science and what does that mean for human subject research protection?

One answer might be that China was always this prolific in science but was not as great as touting their work. Thus, these slates of discovery might just represent a change in marketing.

Another answer might be that China is increasing its funding of science at the same time that US investment is remaining unchanged or declining. For the past 40 years, the proportion of science research funded by the federal government has steadily declined. In 2016, federal science research dollars represented 0.6% of GDP, a decline of over 17%in the years 2009-2014. At the same time, China has made a huge investment in scientific research, experiencing growths of 20.5% per year during the 2000s, and 13.9% per year in the 2010s. This largesse is drawing US researchers and students to China. While the United States still spends more than any other nation on research, other countries are ramping up their spending at a fast rate and will likely surpass the US in the years ahead.

A third answer is that China has a much larger population (1.2 billion v. 330,000) and can do more science based on sheer scale. Consider that Chinese colleges and universities enroll 37 million students. The U.S. enrolls 16 million students. There are more people do the work there.

Fourth, US research has also had to deal with political concerns over its work. For example, stem cell and embryonic research has been waylaid by a conservative movement in the US that views life beginning at conception and any manipulation of an embryo as immoral. Thus, much US research has focused on “getting around the moral quandaries” such as developing totipotent cells from adult cells. The current Administration is also reviewing fetal tissue researchand whether it should be allowed to be funded or even continue. Putting money and resources into workarounds that other cultures do not have, means other countries have taken the lead in these areas

A fourth answer is that Chinese human subjects regulations are different than the US. There is a system of human subjects ethical review for research but a lot of theinfrastructure is still under developmentincluding the lack of a national ethics committee (only the Ministry of Health has a permanent group). There is also more ethics training for researchers in the US than currently in China. According to one author, China has good intentions toward protecting human subjects, but implementing that process has proven to be inadequate. This difference in regulations and philosophy means that when research from China is released, it often raises ethical questions. When He announced the birth of twin girls from gene edited embryos, we soon learned of several ethical problems: He did not inform the government (his funding sponsor), may have lied to his university’s review committee, and had a questionable consent process for the couples involved.

In the experiment that produced sickly macaques to build them as human disease models, other ethical concerns were raised: Are the benefits to be gained from research worth the risk to the animals? Is it acceptable to create sick monkeys and is that a good model for studying human illness? Beyond the animal rights issues are questions over the ethics of cloning and genetic engineering (leading to live births).

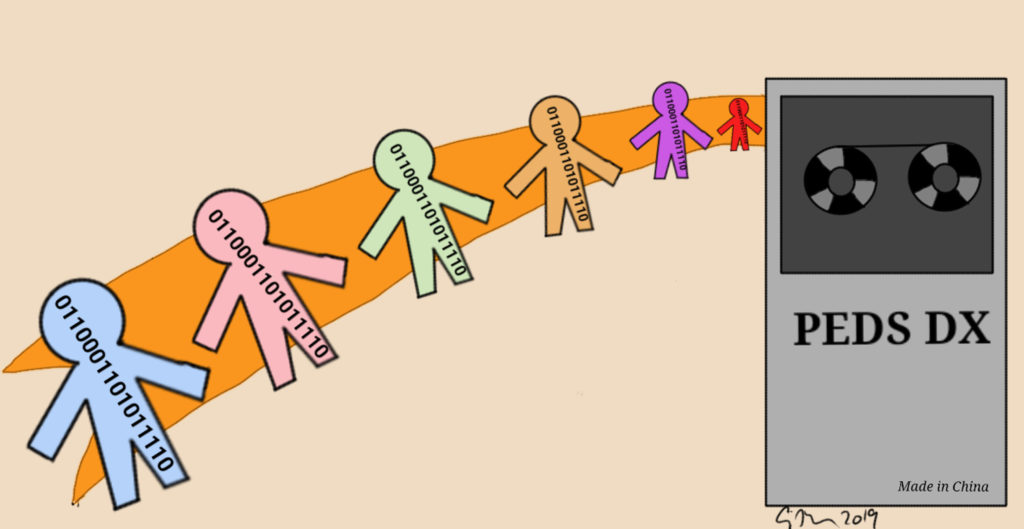

A letter published in Nature Medicinethis week announced the development of an A.I. system that is more accurate at diagnosing disease than the best doctors. The AI was developed by feeding it 101.6 million “data points” from 567,498 patients and “1,362,559 pediatric patient visits.” The authors found that the AI is “a means to aid physicians in tackling large amounts of data, augmenting diagnostic evaluations, and to provide clinical decision support in cases of diagnostic uncertainty or complexity.” Reading this, I immediately wondered whether the records were de-identified, if patients (and their parents) were consented for the use of their records, and if patients (and their families) were even told about this use of their records. This study raised those issues because big data studies in the US are usually de-identified, but notification and consent have been absent so far.

The authors supply the words needed for publication in a Western (specifically US, even though Nature is a UK company) journal. In an appendix, the authors state the study was approved by two hospital IRBs and “complied with the Declaration of Helsinki”. They write that there was “informed written consent” at the “initial hospital visit” and that “patient sensitive information” was removed alongside de-identification. A final note says that the data “were stored in a fully HIPAA compliant manner”. This statement raises a number of issues. The paper says this was a “retrospective study”, so were patients consented before the study had even been proposed? Or were records only included after consent occurred during an office visit? If the latter is the case, that what is the “initial hospital visit”? Without a copy of the informed consent document, it is difficult to know what information the family was given. The authors also provide no information about what “patient sensitive information” is and who made the determination as to whether information was sensitive or what standards were used. An additional consideration is that the Declaration of Helsinki is geared toward clinical trials and is silent with regards to records except for a requirement of protecting privacy and confidentiality.

The only nod to questions of ethics in the paper are a note that the raw data is available to the public: “To protect patient confidentiality, we have deposited de-identified aggregated patient data in a secured and patient confidentiality compliant cloud in China in concordance with data security regulations.Data access can be requested by writing to the corresponding authors. All data access requests will be reviewed and (if successful) granted by the Data Access Committee.”While I did not request access, clicking on the provided link showed that the data is being kept on an Amazon server. Given that records can easily be re-identified today and that servers are hackable (it’s not a question of whether a database will be hacked but when), one might wonder how safe this data is.

One of the challenges of building AI systems is that they tend to duplicate the biases of the records that are loaded. The famous examples are about facial recognition algorithms that have had trouble identifying female and non-white faces because there are many fewer of those records uploaded. In this study, the database was predominantly Chinese (of which 92% are of the Han ethnicity) and that may have implications for diagnosing patients in other populations and regions of the world.

Lastly, I wish to emphasis that concepts and words have different meanings in different cultures. Twenty years ago when I was part of a joint US-China bioethics meeting there was a long discussion over the virtues of privacy. We learned that the US understanding of this concept is very different from the Chinese. In the US privacy is positive, protecting oneself from others and from the government, whereas in China privacy has a negative connotation of hiding dark secrets in a culture that values transparency.

What this means is the need for more international and publication standards for research using human subjects and medical records of human subjects that go beyond simply using some key words (after all, He originally claimed ethics review as well, but it turned out he was not forthcoming in that application). Instead, journals and funders should require original documents. For example, journals should require copies of the informed consent document and the IRB approval letters (some already do the latter). When HIPAA was created, databases were not on the cloud and hacking was not as common, thus the requirements for electronic storage and protection should be upgraded. I would recommend that data only be kept on air-gapped computers (ones that are not connected to the Internet which is the only way to secure against hacking). Additionally, patients should be notified when their medical records will be used for research before those records are uploaded into a non-clinical database and given an option to opt out of being part of the research. While these new challenges to research ethics are not insurmountable, they do need to be examined and standards established soon. The researchers are not waiting for the ethicists to catch up; they are going ahead with their studies. We need to act quickly.