by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Some weeks when I think about what my blog will be about, there are very few relevant items in the news. And then some weeks there are too many things to talk about. This week is one of the latter. Besides the Graham-Cassidy bill (which I discussed in detail last week), there is the lack of any movement on renewing the CHIP program, the patient who may have had a change of consciousness after vagus nerve stimulation, or even the Ohio law that does not allow minors to consent for their own treatment in any circumstances, meaning that teenagers in labor cannot have pain relief (i.e. epidural). To me the most concerning story this week is one that deals with the most basic issue: The continued human suffering in Puerto Rico after Hurricanes Irma and Maria hit the island.

One week after the storm, only 11 of 69 hospitals on the island of 3.4 million people have power. Two patients on life supporting technologies died on Monday because the hospital had no fuel for the generators. Food, water, and fuel are in short supply. Communications are down (9-1-1, cell phones). Even when a hospital has some resources, often staff cannot get to work because of a lack of fuel and roads that remain blocked with storm debris. Without power, a hospital cannot provide lights, or ventilators, or air conditioning to protect its patients.

Patients are starting to get sicker. With no power, there is no dialysis for the 5,600 patients on the island who rely on that technology to stay alive. For people with chronic diseases that require medication, they are running out of their supply on-hand. For someone who needs insulin, even if they have enough, the lack of refrigeration may make their supply unsafe. Even though a portion of the island’s pharmacies have re-opened, the lack of available transportation makes restocking and patient access difficult. The Navy is sending Comfort, it’s hospital ship, which has 1,000 beds and 12 ORs but it is still several days away.

The big concern now is public health outbreaks. The heat, lack of food and water, and lack of infrastructure (water, sanitation, power) could quickly lead to a spread of infectious disease. Without clean water, diarrhea and cholera become a concern. If bodies cannot be buried quickly, there is a risk of diseases spreading. With heat and no water, dehydration becomes a concern. Standing water from flooding poses another danger since it provides a rich feeding ground for infectious disease.

The big concern now is public health outbreaks. The heat, lack of food and water, and lack of infrastructure (water, sanitation, power) could quickly lead to a spread of infectious disease. Without clean water, diarrhea and cholera become a concern. If bodies cannot be buried quickly, there is a risk of diseases spreading. With heat and no water, dehydration becomes a concern. Standing water from flooding poses another danger since it provides a rich feeding ground for infectious disease.

There is not a lot that bioethics has to offer the residents of this U.S. territory in terms of alleviating their situation right now. However, we can acknowledge that under justice and solidarity, there is a need for the mainland U.S. to help. We need to make better efforts to get people on the ground who can unravel the transportation issues and get supplies to the people. Even in public health ethics, when thinking about fair ways to distribute goods, we rarely think about a situation where the goods cannot reach the people. In crisis planning (which I wrote about a few weeks ago), there is a presumption that at some point additional resources in terms of supplies and personnel will be available (We may to revisit those relief plans). Consider that few people would think about road crews and cell tower repair people to be first responders, but as Puerto Rico is teaching, those are essential problems. There are doctors, nurses, and truckers on the island but no one can reach them on the phone and the impassable roads (and lack of gasoline) makes it difficult for them to get to their worksites. It’s not enough to have volunteers, people to rebuild the electrical grid, truckers, and road repair crews available—we have to know how to best use them and how to get them where they are needed.

There has been a slow response to this natural disaster. The President’s visit is scheduled for a full two weeks after the most recent storm passed. When Harvey hit Texas and when Irma hit Florida, the response from the federal government was swift. This time it has been stilted. One claim holds that the isolated location of the island is a challenge—there are no roads to drive in trucks from the mainland and the airports were shut down. Others have suggested that the administration may not have been aware that Puerto Rico is part of the U.S. Still others suggest that racism is involved: That a territory of people who primarily speak Spanish and did not vote for the President (because residents of Puerto Rico cannot vote for President nor do they have members of Congress, only observers) may not come to his attention since they do not benefit him or form his base. Yet another perspective holds that the response may relate to money and Trump’s failed golf club resort on the island.

Aid has been slow in coming. A large amount of food and water has finally arrived in San Juan, but given the lack of fuel, undamaged roads, and truckers, there is no way to unload and distribute these goods. The White House waived the Jones Act for 10-days starting today which will allow non-US ships to bring supplies. The administration has also banned all members of Congress from visiting the island supposedly to allow all transport to be used for aid though there may be public relations concerns at play.

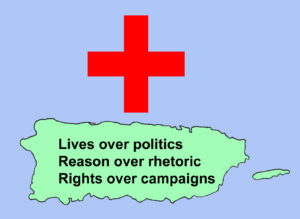

What bioethicists can do is bring attention to this suffering. Rather than jumping on a bandwagon and analyze the latest technological advancement or raising warning flags about health bills that likely never had a chance of becoming law, we can write about social justice and the need for humanitarian aid. With academic freedom we can choose where we put our efforts and what we prioritize: There is a need to write about the new technologies and I may do so tomorrow, but today I am prioritizing basic human needs. In a week that saw more front page stories about the NFL and kneeling than about a humanitarian crisis in our own nation, we can be a voice of reason—lives over politics; reason over rhetoric; and rights over campaigning.