by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

As you may be aware, the U.S. House and U.S. Senate are in conference over a major tax bill. Each chamber of Congress passed different versions of a 2017 tax reform bill. The next step is for representatives from each chamber to negotiate the differences and then to present a reconciled bill for final votes. The GOP has an ambitious timeline of completing reconciliation by the Christmas holiday meaning that the bills are being rushed and not receiving careful discussion and debate. What is important for the world of bioethics with these bills is that they contain significant changes to the health care landscape and even a few easter eggs that will effect bioethics practice.

Education Changes

Let’s start with changes to how a person becomes a health care provider or a bioethicist—higher education. In the Senate bill, taxpayers would be capped at $10,000 in annual deductions for state and local taxes (income, property, school, etc). [<–In Final bill]  Previously these had been fully deductible. The concern is that people in high tax states may rebel and raising funds for local schools and higher education will become harder. Both bills impose a 1.4% tax on the endowments of higher education institutions . The Senate version would only place this tax when the endowment reaches $500,000 per student [<–In Final bill] The House version is when the endowment reaches $350,000 per student. For some schools, this new tax reduces the dollars available for campus spending. The tax would apply to our largest and most prestigious universities creating a tax on intellectual leadership.

Previously these had been fully deductible. The concern is that people in high tax states may rebel and raising funds for local schools and higher education will become harder. Both bills impose a 1.4% tax on the endowments of higher education institutions . The Senate version would only place this tax when the endowment reaches $500,000 per student [<–In Final bill] The House version is when the endowment reaches $350,000 per student. For some schools, this new tax reduces the dollars available for campus spending. The tax would apply to our largest and most prestigious universities creating a tax on intellectual leadership.

The House bill would tax tuition waivers that graduate students often receive to cover the cost of their classes [<–NOT in final bill]. Even though students never see the money, they would be taxed as if those waivers were earned income. If you work at a university and have a tuition benefit, the bill would tax that as well [<–NOT in Final bill]. Thus, if your child goes to college through the benefit, you would have to pay tax on the value of that waiver. The House bill eliminates the ability for people to deduct interest on their student loans and consolidates the learning credits available for people enrolled in coursework [<–Not In Final bill]. For more information on the changes to higher education in the two bills, refer to the Chronicle of Higher Education.

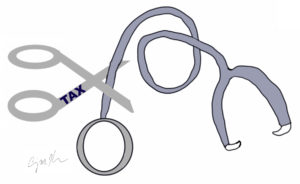

Health Care Financing Changes

The bills also offer changes to how we pay for our health care. Under the Affordable Care Act, every documented resident and citizen in the U.S. is supposed to have health insurance. This requirement is known as the mandate. The Senate version cuts this mandate. According to nonpartisan analyses, this would result in 13 million fewer people purchasing insurance. Most likely, those opting out would be younger and healthier, which would necessitate an increase in premiums and other insurance fees.

For patients with high medical expenses, the current tax law allows them to deduct expenses over 7.5% of adjusted gross income. About 8.8 million Americans take advantage of this deduction. However, the new House bill eliminates that deduction meaning more people would suddenly find their monetary outflow significantly increased. The Senate version increases this deduction so the final policy will be part of the conference.

For children who had received health insurance coverage under the CHiP program that expired on September 30, some state programs are running out of money. CHIP provides coverage for 9 million children and 370,000 pregnant women. Congress has expressed little interest in renewing this program. Additionally, the bills propose cutting community health centers.

Medicare provisions that mostly help rural hospitals expired on September 30 and have not been renewed. This annual legislation supports the dependent hospital program and the low-volume adjustment. The result is that hospitals need to make up 19% in lost revenue. Forty-four percent of rural hospitals are operating at a loss in 2017. Another cut instituted by the new Administration slashes $1.6 billion in funding for “safety net” hospitals that use the 340B drug discount program.

The question on most people’s minds, is how does the country pay for a tax cut bill that adds $1.4 trillion to the deficit? The answer has come from House Speaker Paul Ryan. Ryan said congressional Republicans will try to reduce spending on Medicare, Medicaid and anti-poverty programs next year. In other words, rollback the New Deal and the Great Society programs. A deficit-control law requires that increased costs be offset with cuts and this will affect public welfare programs. Ryan believes he has Trump’s about reining in Medicare, even though the president pledged during his campaign not to cut spending on any entitlement programs. Thus, not only may there be less money to pay for medical care, but there may be less money available for helping the poorest of our society.

One way that drug companies are incentivized to produce drugs that have a small market—usually because there are few people with the disease—has been the orphan drug tax credit. This allowed the company to deduct 50% of the cost of clinical testing of the drug. The House tax bill would eliminate this credit, meaning people with orphan diseases are less likely to see products drugs to market.

An amendment introduced by Maine Senator Collins would provide subsidies to the ACA market for 2 years at a cost of $10 billion. The plan would create re-insurance markets to cover the insurers of highest risk people and offer start-up funds to help states to create high risk insurance pools. Collins is on the reconciliation conference committee.

Easter Eggs

In films and video games, an easter egg is a hidden feature inside the game or movie. Similarly, the tax bills, as passed by each house, contain some eggs that will affect bioethics. For example, the tax bill expands who can put away money in a 529, state-sponsored, tax exempt investment plans which can help fund college. One expansion is that this money could be used to pay for private K-12 schooling. A second expansion is that the “unborn” can establish these accounts: “An unborn child means a child in utero,” the provision states. “A child in utero means a member of the species Homo sapiens, at any stage of development, who is carried in the womb.” Thus, for the first time in federal legislation, fetuses and embryos have legal rights.

Consider that a long-standing deduction to help businesses comply with the American with Disabilities Act is set to be repealed in the bill. Small businesses could no longer write off the cost of altering their “architectural, communication, physical or transportation barriers” to help workers with disabilities. The bill would also end the deduction for moving costs if your new job is 50 miles away from your current one,

In another vote this week, the FCC is likely to vote on Thursday to rollback net neutrality. On the surface, this does not seem related to health or bioethics education, but when you dig deeper, it will profoundly affect both. The loss of net neutrality would mean that internet service providers (ISPs) could charge higher rates for fast connections for every individual website. You could pay a different fee to reach Google than you would to reach Bing. You may have to purchase package tiers that would give you different levels of access and speed. If the ISP views a website as their competitor, then you might have no access at all. Consider the push in the last several years toward electronic records and patient portals. I communicate with my physician and can see my records through such a portal. With net neutrality gone, I might have to purchase a higher level of service to be able to access the portal or my provider may have to pay an extra fee to a number of ISPs to ensure that patients can have access. Like most professors, my courses all have online components through our course management system.

This is how students submit assignments, find course materials, and even take exams. With the loss of neutrality, students may have to purchase higher ISP tiers that give them access to the university or the university will have to pay higher rates to be available to students. Even websites that allow doctors to track patients through remote monitoring may not be available without higher internet costs.

When I teach justice to my students, I often discuss Rawls’ maximin rule—that the greatest benefit should go to those who have the least. These bills might best be described as minimax1—the greatest benefit goes to those that have the most. This is not my analysis of the bills, but rather the assessment of one of the architects, Senator Grassley of Iowa: “I think not having the estate tax recognizes the people that are investing,” he said, “as opposed to those that are just spending every darn penny they have, whether it’s on booze or women or movies.”

1 Minimax is technically an economic and games theory term denoting an approach to minimize possible losses. In this statement, minimax is used to mean maximizing the benefits to the minimum number of people–a play on words of what could be the opposite of Rawl’s maximin.