by Olya Kudina and Lori Bruce

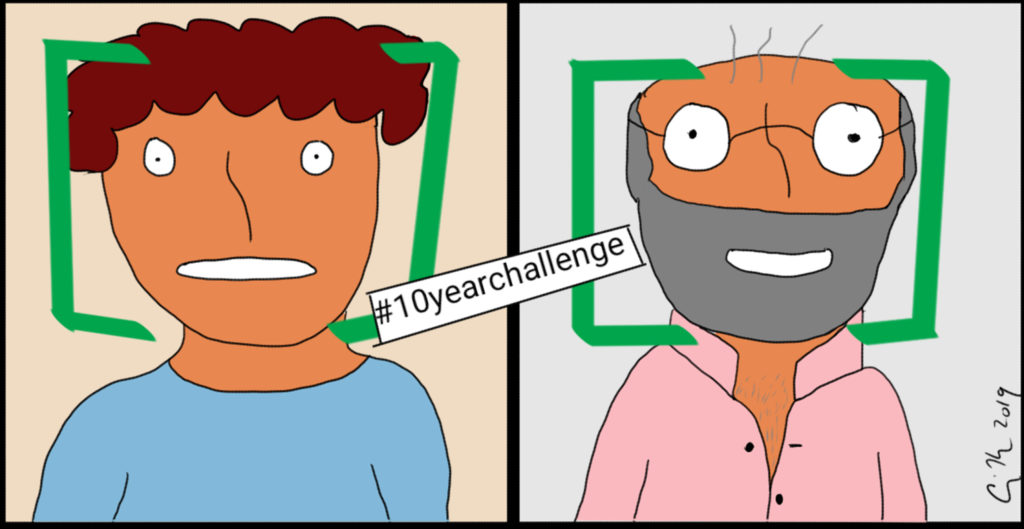

Online social spaces maintain an increasing presence in our lives. Yearly, people upload around 1.2 trillion photos on social media and share personal stories and milestones through their social networks. It is fair to say that online communications are here to stay. The #10YearChallenge is a recent manifestation of photo-sharing across social networks. The challenge purportedly started as an initiative to post two photos of the same person with ten years’ difference between the images. The challenge proliferated across social networks with people predominantly comparing the way people age, and occasionally wandering toward spin-off challenges such as illustrating environmental degradation over time. Users of social networks were hardly the only ones intrigued by the photos: as suggested by strategic tech consultant Kate O’Neill, a large mass of curated photos with a specific time context presents a tempting opportunity for the private sector.

Human faces are a unique form of identification, a type of biometric data most specific to a person and difficult to change. Facial recognition software, trained on a voluminous number of images with specified time stamps, can enhance the algorithm’s ability to identify ageing. Once properly trained, the algorithm can predict how a person will look in future or how a person looked when younger, so it’s no surprise that companies would wish to use the #10YearChallenge dataset. While there are positive applications of facial recognition, such as solving cases of missing children and identifying disaster victims, use of #10YearChallenge photos by third parties is anticipated and may be of concern.

#10YearChallenge photos could be processed to consider the following questions:

- Are there facial markers associated with dementia (or other costly diseases) that appear before the onset of behavioral markers?

- Do people with more online friends age “better” than those with fewer friends?

- Are there physical aging trends that delineate those who belong to a certain disease support group, political party, or other affiliation?

The results of such analyses could guide health insurance prices for targeted groups or specific individuals. Such a potentiality is not far-fetched, as suggested by the current uses of facial recognition, ranging from identifying “stress, fear, or deception” in passengers to enhance US airport security to the detection of gender and skin tone in digital photos. Moreover, machine learning scholar Yilun Wang and psychologist Michael Kosinski recently discovered that facial recognition algorithms are better than people at identifying sexual orientation from photos, cautioning against threats to safety and privacy for gay men and women. Journalists George Joseph and Kenneth Lipp reported on another algorithm, developed by IBM on request of the New York Police Department, that can identify people based on skin tone to help police search on this parameter. Most of these algorithms are immature and need more images to increase the accuracy of their algorithms. According to MIT researchers Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru, the skin tone algorithm is more likely to falsely identify people of color because it detects lighter faces better than darker ones. Photos from the #10YearChallenge could refine such algorithms.

Michael Kuperstein, who develops business applications of facial recognition, suggests that the current HIPAA regulations may drive US healthcare to use facial recognition instead of passwords to tamp down on identity fraud and to allow patients to access their portals. Researchers from Pace University suggest that in healthcare, facial recognition can help to measure a patient’s pain intensity, detect genetic diseases, and assist in diagnosis of psychiatric or neurological disorders. With this in mind, it’s not surprising that for-profit healthcare companies may be interested in facial recognition.

The #10YearChallenge and its underlying potential for facial recognition present concerns relating to individual privacy, autonomy, consent, justice, and fairness. In some ways, accounting for biometric information on social media has a close affinity with traditional bioethical concerns. It challenges the traditional notion of informed consent: when people use social networks, few assume that their 40-year old birthday photo may inadvertently contribute to screening suspected terrorists at the airport or contribute to raising rates on health insurance premiums. However, training recognition systems on facial images collected for different original purposes is a widespread problem. For instance, IBM used data from millions of unassuming people acquired from the CCTV system in New York to develop the skin tone algorithm mentioned earlier. This “open laboratory” approach, coupled with lack of government and industry oversight, paves the road to potential violations of civil rights and liberties related to selling the users’ biometric data to governments, insurance companies, and other businesses.

Facial images collected from social media may have tremendous value to healthcare companies and medical researchers. Bioethics may be helpful in considering whether limits should be applied to the use of social medial data within the context of healthcare and medical research. Bioethics could also contribute to the development of ethical guidelines for healthcare companies to guide usage of social media data within health and medical applications.

In closing, bioethics may also wish to draw upon philosophy of technology to consider the less evident technological impacts. Social networks mediate our relation to the self and others by amplifying some aspects of reality while reducing others, while influencing our moral inclinations and decisions. Consider how the #10YearChallenge encourages us to evaluate the passage of time by focusing only on the visual representation of people, downplaying other aspects of progress, memorable events and life changes that cannot fit into a picture. Digital technologies increasingly regulate our practices of remembering and forgetting, presenting us with old photos not in view of a meaningful moment but guided by precise time intervals. The #10YearChallenge also affects the perception of the self: consider how “selfie” culture powered by airbrushing perpetuates unrealistic standards and obsessive pursuits of perfect looks. A recent JAMA study suggested that “selfie” culture triggers body dysmorphic disorder, encouraging some to undergo plastic surgeries and Botox treatments to look like the edited images of themselves. Thus, social media are not neutral communication tools and may even increase vulnerabilities to certain psychiatric disorders: a new pathway to public health risks.

The cases of Henrietta Lacks, John Moore, and Ted Slavin challenged bioethics to reconsider the principles of informed consent and genetic data rights and responsibilities. Similarly, the #10YearChallenge may nudge us to more broadly consider the impact of social media on our health and civil liberties.