by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

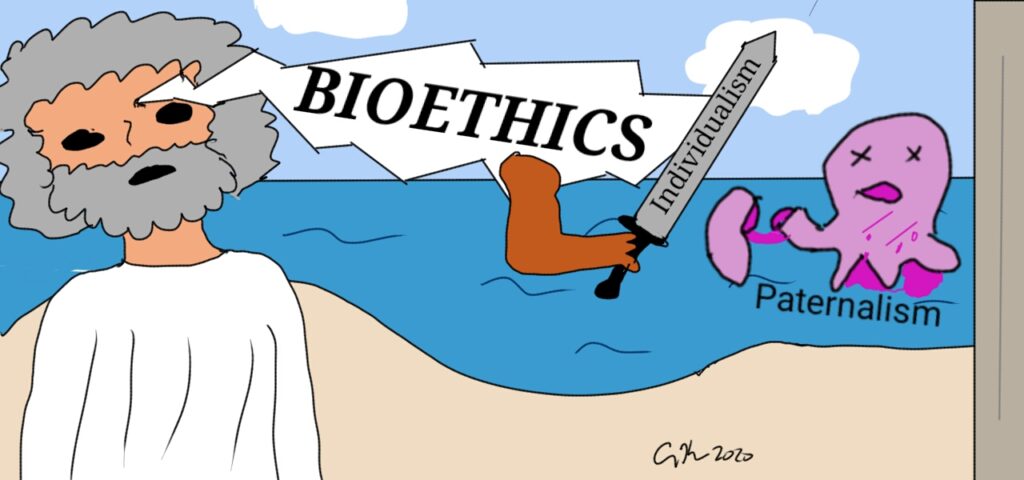

In the mythology of the founding of bioethics, we learn that this nascent field sprang whole from the forehead of Zeus to slay the paternalism that was practiced by the children of Apollo. Less dramatically, our founding legends hold that bioethics came into existence in large part to bring a turn to autonomy where the patient was a partner in medical decision-making rather than being am object that a physician treated. Similar to other civil rights movements of the late 1960s/early 1970s, bioethics sought to empower the patient to have a voice and control over their body.

Bioethics was most likely to form in the United States, which has long held a reverence of the individual. One of our first unique contributions to philosophy was the idea of self-reliance, the title of a work by transcendentalist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson. In Emerson’s idea, the collective society is a problem because it demands that people conform to its will: “Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members.” Instead, we should be individuals, listening to our own advice; we alone are responsible for our happiness: “Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind. Absolve you to yourself, and you shall have the suffrage of the world.” In short, Emerson lays a foundation for the American character—that of the individual responsible to and for oneself. From these early writings, Americans have valued the individual over the collective, personal freedom over the common good, and personal responsibility over social determinants.

Centering the individual above all places responsibility for illness on the individual. The philosopher Charles Taylor diagnosed America as suffering from “individualism”, placing primacy on individual experience and fulfillment. If the individual is final arbiter of what is good and if the individual is the final arbiter of what is true, then there is no moral commitment to one another. Individualism’s effects can be seen in modern politics that goes so far as to say that facts and reality are different for each person (Conway’s “alternative facts”).

This worship of the individual makes those of us in the West and the U.S. in particular a “weird” minority in the world’s populations. Joseph Henrich, psychologist and economist, says that “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic” (WEIRD) countries evolved out of the Roman Catholic Church that made marrying (and breeding) between cousins immoral, thus breaking family bonds. Henrich also says that the growth of guilds in the middle ages led to a system of competition that was individually focused. His message is that WEIRD cultures are in the minority in human experience. The majority of populations are more communally-focused cultures.

The implications of individualism on health and medical care in the United States have been profound. Public health and medicine in the U.S. are two separate disciplines: One is well financed and viewed generally positively and the other is continually underfunded and viewed with derision as “health care for the poor”. Guess which one is about individual approaches to health and which is about communal approaches?

In the case of a response to COVID-19, perhaps our national and personal dysfunction might, in part, be the fault of bioethics’ legendary odyssey to move medicine from paternalism to autonomy. Part of the failure of this country to respond to COVID-19 as well as other nations have can be seen in the lack of a coordinated national response geared toward the common good. It can also be seen in individual’s who reject actions that protect their communities: Refusals to wear masks, partying in large crowds, attending huge indoor rallies, going to school or work even when having COVID-19 symptoms are evidence of this view. Under individualism, one has no responsibilities or obligations for the common good because everyone is self-made (thus stories of being self-made people even when your career starts with over $400 million from a parent). There is no sense of “we are all in this together” or “it takes a village.” Ideal autonomy rests on this image as well, that we are islands unto ourselves and should make rational choices free of outside influences (including effects on family; or taking their needs into account). We regularly teach autonomy as meaning the patient as an individual alone should make the choice.

The harm of individualism can also be seen in approaches to disease where instead of seeing COVID-19 affecting communities of color at higher rates than white populations as evidence of social injustice, the individualist blames the sick person for their genes or for not moving out of a polluted neighborhood. The fault isn’t lax environmental regulations, systemic racism, or companies that pollute with abandon, but people living in poverty who just don’t move away (never mind there are no affordable alternatives). “You have good genes, you know that, right” said President Trump. “A lot of it is about the genes, isn’t it?” Individualism in this manifestation aligns with racist and classist undertones.

Consider this recent quote by Trump discussing why COVID-19 is not a real concern, “It affects elderly people, elderly people with heart problems and other problems. That what it really affects”. This ageist statement says that the person (by being old, or sick) is responsible for getting a highly infectious virus. If the individual is responsible, then the community has no obligation to act. Under such thinking, COVID is not a world-wide problem, it is a problem of people who are old, sick, and have “bad genes”. In other words, it’s an individual’s problem (and that also raises the specter of racism, ageism, and ableism).

Is bioethics at least partly at fault? Have we pushed this idea of autonomy and individualism in medicine and other life sciences to the point where a communal and coordinated federal response is “un-American”? Bioethics has been an acolyte of the church of individualism, spreading its gospel around the world.

Bioethics has pushed too far in the direction of the individual and needs to have a turn toward the importance of the community and the common good. Those who have been working in public health ethics for the last 20 years have been trying to lead the field in this direction. An individualist approach to the plague is “how do we justify limiting people’s liberties” (e.g. access ventilators, PPE, etc.; isolation & quarantine). A communal bioethics asks how we can reduce morbidity and mortality with the resources we have. It values populations equally (and sometimes more than) individuals. This may strike some as cold or devaluing humanity, or perhaps even a slippery slope to death camps. But, individualism has failed because Americans are unwilling to sacrifice for one another or even to consider their neighbors. Bioethics can lead, once again, toward a more balanced approach. Although bioethics won’t save the U.S. from the scourge of COVID-19, we may be able to help steer a path that prevents a dysfunctional approach to the next health crisis.