by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Traditionally, a determination of death can only be made by a physician or by a health care provider (including first responder) if there is evidence of brain matter leakage or the head is severed from the body. However, a series of legal cases in the UK and the US is questioning that tradition. The alternative is for courts to determine when a person is dead or to allow each family to decide what is dead for its members.

The High Court of London has ruled that a hospital may withdraw body sustaining efforts from Isaiah Haastrup over the objections of his parents. Isaiah was born lacking cardiac activity or muscle movement. In some ages, he might have been considered “still-born.” Through resuscitation, doctors managed to get a weak heartbeat and supporting technologies have maintained the body. The court ruled that withdrawing care and giving Isaiah palliative care is in the patient’s best interest.

The High Court of London has ruled that a hospital may withdraw body sustaining efforts from Isaiah Haastrup over the objections of his parents. Isaiah was born lacking cardiac activity or muscle movement. In some ages, he might have been considered “still-born.” Through resuscitation, doctors managed to get a weak heartbeat and supporting technologies have maintained the body. The court ruled that withdrawing care and giving Isaiah palliative care is in the patient’s best interest.

Isaiah’s case is similar to last summer’s ruling over Charlie Gaard. In both cases, the court determined that the child’s best interest was to have supportive efforts removed. In Charlie’s case, the concern was that the interventions were causing suffering. For Isaiah, the court felt that continued support would “not result in his recovery and will condemn him to a life of profoundly limited quality.”

These cases have me thinking about notions of what is death and what is life. In both of the UK cases, a court decided that death was preferable to the current existence of these two boys. The question over defining death is a big interest in the U.S. as well. In a forthcoming New Yorker article, staff writer Rachel Aviv offers a detailed look at Jahi McMath’s situation of still existing (without obvious decomposition), 4 years after she was declared dead in California. Jahi’s mother moved her daughter’s body to New Jersey which permits people to reject death by neurological criteria if it violates their religious or conscience beliefs. A recent California court ruling held that Jahi may not meet the legal conditions of brain death in California and leaves that final decision up to a jury in a future trial.

Death by neurologic criteria is legally noted as loss of function of all parts of the brain including the brain stem. As Aviv explains, scans have shown the loss of McMath’s brainstem but that parts of her cerebrum are intact. In blood flow studies soon after her death, McMath’s brain exhibited no activity.

Many have questioned the notion of brain death, which was adopted in the wake of the need of organs for transplant. Some have stated that what is called brain death may be misdiagnosed in some people. Instead they may be in minimally conscience states or ischemic penumbra. In IP, brain flow is restricted and reduced such that it may look like brain death on scans.

If the courts (or a jury) decide that the current definition of death is inadequate or wrong, then determining and even defining death could be removed from the purview of science and medicine. Who then would determine when a person is dead? One possibility is to go back to the pre-Harvard definition where death was the cessation of cardiac activity. Of course this would mean once a person was resuscitated and connected to body supporting technology, that person could never be removed from such devices since the act of withdrawing would fall into the realm of homicide. Consider that since 2005 in Israel, it has been illegal to turn off a ventilator on someone who is dying or has no hope of recovery. In this small country, these patients exist on hospital wards, long term care facilities, and sometimes with home health care. In Israel, life, death, birth and marriage are controlled by the religious authority and Judaism defines death as the cessation of breathing: For the most part, ventilators are not turned off.

The big implications is for organ donations. Scrapping death by neurologic criteria means we either would have to scrap the dead donor rule or cease doing cadaveric organ transplants. In the former, we could consider taking organs for people who are “on their way to death,” though this may run afoul of murder laws and could be distasteful to most people. Such moves could spur development of mechanical, cloned, or stem cell created replacement organs to avoid the issue. A second major implication is who would pay for the support of these patients? In the McMath case, her body’s care has been paid for by online fundraising, some foundations, and by Medicaid. She is one case but what would happen if thousands or even millions of people are kept functioning in this manner? In a society that does not view medical care as a right, would the machine-dependent gain a right to supportive funding at the same time that the active living would not have a right to even basic care?

Other than having courts decide every claim of death or eliminating neurologic criteria, the other option would be to have families decide on a definition of death. This is the approach taken in Japan where families can choose to be governed by neurologic criteria of death which allows their loved one’s organs to be donated. Under this view, rather than having a national (or state) definition of death, families could choose under which criteria they would have their deaths determined. Cardiopulmonary and neurological criteria could be two schema but some might opt for a medieval definition of bodily decay or even some societies where a person is dead when they no longer contribute to the well-being of the family. These examples are arguments ad absurdum but do demonstrate that even if family choice is used to decide when someone is dead, there will need to be limits around such decision-making.

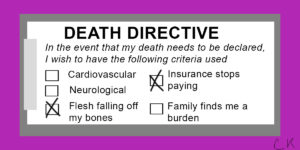

Should I amend my advance directive with a statement on which determination of death schema I wish used for me? Perhaps as part of hospital admission, every patient should have to select their preferred framework. Maybe hospitals need to adopt and circulate policies: “In this hospital, we consider a person dead when….” At the very least, this topic needs to be part of our end-of-life conversations with loved ones, physicians, and medical powers of attorney.

If we do allow the individual choice or even selection among options, then do we require health care providers to treat these bodies? With the new DHHS agency for conscientious objection, we may have no choice but to permit physicians to reject neurologic criteria for death and refuse to withdraw body supporting technologies, even if the family insists. Or could a physician declare a conscientious objection to providing support to such a body? Would insurance be required to pay for their upkeep? Can an individual who chooses decay as their determination of death truly make a financial claim on the next generation’s retirement funds and college savings to pay for their maintenance? How do you tell a child that they cannot go to college because the money has been used to “keep grandpa going.” Inevitably, these decisions set up a battle of resources between the generations.

This year is the 50th anniversary of the ad hoc Harvard meeting on the determination of criteria for brain death. The milestone is being noted in a conference to be held at Harvard Medical School looking at the past, present and future of the idea of brain death. That original protocol was controversial but in the intervening decades the notion of death has become culturally ensconced as somehow objectively true. I know that I have written about these ideas as such. As these current court cases demonstrate, those of us who entered bioethics after this time have forgotten about (or more likely were never aware of) the controversial and tentative nature of these recommendations. Given the current set of court cases, many people and jurisdictions may rethink their approach to determining death. It is not inconceivable that some states may adopt New Jersey’s approach. Individual hospitals may find families requesting alternative views of death or rejecting the legal definition. And depending on the outcome of the McMath case, we may be forced to revisit the current framework and our entire approach to the end of life: This last decision will be in the hands of 12 California jurists.