by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Last week I had to visit a doctor at a large urban medical center (it was a minor yoga injury). The office was fairly new with lots of chrome and glass. There was a large row of desks for admittance into this specific clinic. When my deli-ticket number was called, I had to provide the usual information: insurance, name, birthdate, reason for being there. The surprising part was when we got to the general consent document. I was shown a laminated, 3-page print and an electronic signature pad. In most of my previous medical interactions, this part of the processes consists of me being handed a bunch of forms including a general consent, medical history, a clipboard and a pen. I take these to a seat and fill them out. Having a bioethics background (and being the son of an attorney), I usually edit the consent document. Often these general consents have elements in them to which I will not agree. For example, one time the consent gave the physician authorization to speak to anyone about my private health information. I wrote in that it was limited to other people in his office and health care providers involved in consulting about or providing my health care. Sometimes there is a clause stating the patient agrees to be contacted by marketers who might sell be products and services. I always cross that one out. I initial all my changes and hand it in.

I would say that 90% of the time, no one says anything about my changes and simply files the document. On the rare occasion when someone has noticed, they usually ask me why and we discuss it. This contact provides a nice conversation and opportunity to educate someone who may not be aware of some of the nuances. In two circumstances they asked if they could use my notes in revising their documents. I always agree.

My surprise in this most recent encounter was when I asked for a printed document because there were things I simply would not agree to. The response was that over the weekend they moved to a new electronic system and without an electronic signature, they could not go on to the next admission page. No paper copies were available and paper signatures were not acceptable. No alterations could be made on line. In tech terms, the record had a “hard stop” at this point. The admitting person called over the office manager who informed me that I either signed as is, or I could not see the doctor. I explained to him that it was not “informed” nor “consent” if I had no option other than to agree to everything or leave. He agreed with me and said all he could was call risk management. I said that was fine and I would wait. It was clear he figure I would not accept this offer. Instead he said that I should sign for my appointment and then he would help me rescind it right after my appointment. He seemed frustrated by the lack of flexibility in this system and seemed to welcome a challenge to how things were being done. When I said that I would be writing a blog about this, he said that I should.

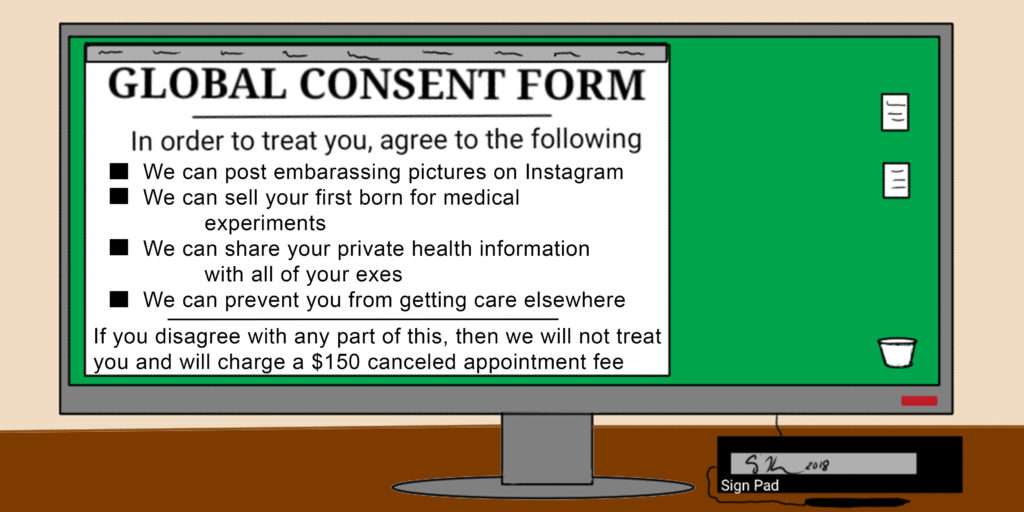

In this particular global consent document, there were several issues about which I had concerns. First, there is a provision that I could be contacted about participating in research since they are involved with advancing knowledge. Of course I can always say no or just simply not answer the phone. But if I do not want to be contacted, then I have to call an office and ask to be removed from a registry. While such an opt-out system may be useful for increasing the number of people participating in research, it does seem disrespectful of autonomy. Second, I had to agree that any excess tissues or body fluids drawn would be available for them to do research on “with or without my personal identification.” There is no opt out for this piece. I could not choose “you can only use my tissues anonymously,” or not at all. Although I was unlikely to have such procedures as part of my care for this visit, I did not want to give them this permission because I still believe in privacy. I said that if they were trying to create a biobank and using materials this way, then they should create a consent for biobanking instead of trying to sneak it past patients. Third, the consent gives the institution permission to contact me for fundraising. I can opt out if I call yet another phone number. Fourth, the consent states that all of my private health information is available for research, to regulators, and providers not part of their institution, and to anyone in their network irrespective of whether they are involved with my care. When I looked up who is in this network, I found a list of several hundred national and international partner institutions whose only commonality are that they are customers of one particular electronic medical record program. Obviously 99% of these people and places will never be involved in my care. I can opt out of this as well, but I have to send an email or postal note this time. Exercising my medical privacy rights should not require extra opt-out steps.

Two days after my visit, I received a “patient satisfaction survey” which also included a note that I would be sent future surveys about my care at the institution. If I wanted to opt-out of taking surveys for them, I had to click through to yet another opt-out form. The consent document said nothing about being contacted for such surveys or aopting out. Needless to say, I gave them the lowest rating for the question “concerned for my privacy.”

Clearly parts of this global consent are being placed in there to avoid having to get separate permissions and to increase participation since most people are unlikely to go through the multiples steps to opt out. However, even for a motivated person, requiring a patient to contact four separate divisions to opt out of provisions is onerous and an undue burden that violates the ethics of autonomy and privacy. Whereas in the past, I could have had a conversation with someone about this, chosen not to sign portions, or even struck out portions, an electronic form that is capturing only a signature image and is a hard-stop in the computer process denies me those rights and freedoms. The document I saw was not about “informing” me nor was it about “consent.” It was about my obedience.

The process of making phone calls and sending emails to opt out of all portions of the document that are available took me about an hour. That is an hour longer than it should have. I have also forwarded my concerns to the ethics committee and the hospital’s legal services. I will probably go elsewhere for my care in the future but with everyone going electronic, this may be a Don Quixote move. The problem is that these computer systems are made to force triangles, hexagons, and circles into a square hole. When common sense is sacrificed for ease of programming, one is no longer practicing medicine but obeying a computer at the cost of our humanity.