by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

When I was growing up I recall parents talking about chicken pox parties where parents would arrange to expose their children to a person with an active infection. The idea was to have their kids get sick at a specific time that was convenient to the family. I came down with the disease naturally, the day before I was supposed to leave on the big 5thgrade school trip to a dude ranch. I did not get to go on the trip.

Since then, a vaccine for varicella (varicella-zoster virus) allows children to avoid this disease. At age 1, children receive the first injection and at age 4, they receive a second. Chicken pox by itself is discomforting and at times painful. The disease manifests witha fever, blister-like rashes, fatigue, and horrible itching. Giving into the itch can leave scars. Before the vaccine, 4 million people worldwide were infected each year, with an average of 10,500-13,000 hospitalized and 100-150 deaths annually. The vaccine is credited with preventing 3.5 million cases of chicken pox per year. Currently, there are fewer than 200,000 cases in the US annually.

But perhaps the worst part of the disease, is that the virus never leaves the body. It sits in wait until a person’s immune system is weakened and then it re-appears, decades after the initial infection as shingles. Nearly one-third of the population will develop shingles(about 1 million people per year). One in five people will experience severe nerve pain that can last even after the rash has gone away. Members of my family as young as 40 have had this unpleasant and terrifying re-manifestation of varicella. The disease is infectious (if a person has not had chicken pox or a vaccination) and can be treated with anti-virals. A shingles vaccine is available for adults over the age of 60. While one does not die from shingles directly, outbreaks are correlated with stroke and heart attack at the rate of approximately 96 people per year).

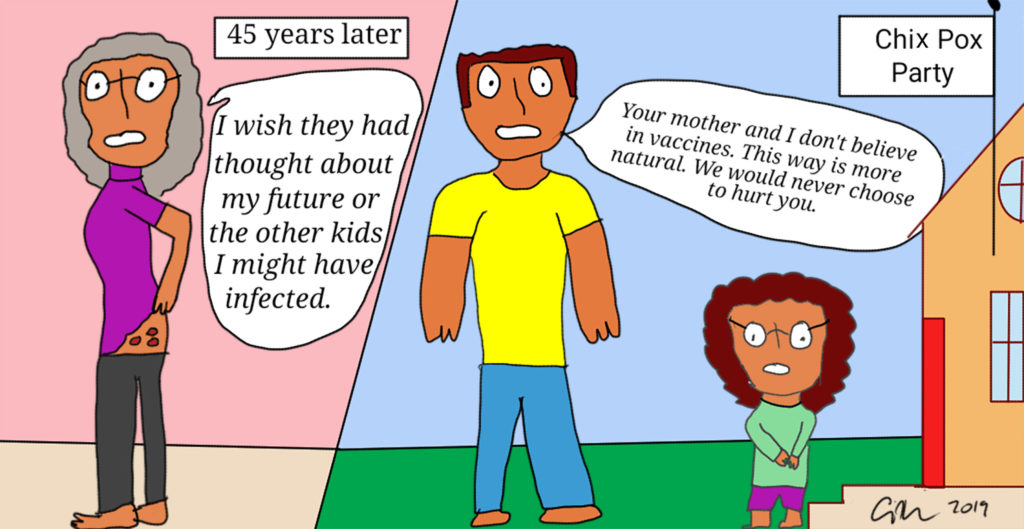

Given the presence of a simple vaccination that prevents childhood misery and adult endangerment, giving the inoculation seems like a no-brainer. Recently, the governor of Kentucky announced that he not only did not vaccine his 9 children, but he deliberately exposed them to the virus at a chicken pox party. While this choice raises questions about parenting styles, it also raise several ethical issues about harm to children and public health.

In several discussion sites, posters have raised the question as to whether not vaccinating a child is a form of child abuse, or at least, neglect. The evidence is clear that not vaccinating puts a child’s health at risk for severe harmand in rare cases even death. Parents do have the autonomy and legal authority to make decisions for their children, but that power is not limitless. This right stops when a parent deliberately or even accidentally endangers a child. But does not vaccinating rise to the level of abuse? Legally, that is a hard case to make. In a study examining cases brought to court claiming child abuse for not vaccinating, researchers only found 9 cases nationwide, in 5 states. In 7 of those cases, the courts did find not vaccinating was a form of abuse. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends only calling child protective services if “vaccine refusal represents an immediate danger—refusing a tetanus shot after a deep, contaminated wound, for instance.” Since the dangers of varicella are longer term (chicken pox as a child and shingles as an adult), they would not fall under this guideline.

Why do parents choose not to give the chicken pox vaccine? This might be part of a larger debate on why parents do not give vaccines (such as MMR). A study out of Texas Tech University found 4 reasons for vaccine refusal: Religion, personal and philosophical beliefs, “safety concerns”, and “a desire for more information from health care providers”. Many states have begun passing laws that remove all exemptionsexcept for medical reason (allergy to a component of the vaccine or immunocompromised). Many of the safety concerns are factually untrue, stemming from Andrew Wakefield’s faked study allegedly showing a link between autism and MMR (a paper that has been withdrawn and disproven by no less than 5 comprehensive studies). As for personal and philosophical beliefs, many of these are being supported by misinformation campaigns disseminated on social media. The social media posts playupon conspiracy theories and fears of “big government” trying to control the population. To combat these false information campaigns, social media sites are stepping up to delete posts that push an anti-vaccine agenda. While some may argue that this violates free speech, there is no free speech to spread misinformation and lies—that is the equivalent of yelling fire in a crowded theater.

This is where individual rights come up against public health. Most of medical ethics is built on the philosophy of liberalism—the presumption that individuals should have the freedom to make their own choices and that the individual is the ultimate locus of control. As the philosopher Charles Taylor states, we have become a society that worships at the altar of individualism, and anything approaching community or social thinking is dismissed. The problem with this approach is that it ignores that there are many things individuals cannot do alone; there are many things that require a community approach. This idea is even built into the US Constitution, to “insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty”. Public health is one such communal space.

In terms of parental choice for vaccination, the individualist perspective takes the form of parental autonomy (the right for parents to make choices for their children) as opposed to a more communitarian approach such as public health solidarity (an obligation to reduce morbidity and mortality in a population). Thus, the question is whether individual choice overrides the health needs of the group. A second perspective suggests that the needs of the group should outweigh the choices of the individual. And another point of view splits these approached and asks why (and when) should individual rights be curtailed to benefit the group? If the individual makes a decision that threatens the group, then that person should be curtailed from activities that may harm others. For example, a student who refused the chicken pox vaccine has been banned from school for his decision. He has the right to make the choice, but because his decision affects others, there are repercussions. This follows Mills’ harm principle where the state has a right, and often an obligation, to step in when a choice poses a liberty threat to others.

A final consideration is whether children should have a right to consent to vaccination even against a parent’s objections. In many states, children have a right to make their own sexual health choices. Thus, a child should also have the right to choose for a medical intervention that benefits themselves and others, even if the parent objects.

As for the governor who chose a riskier health path for his children, he may have been legally in his right to do so, but ethically his choice to place his children in harm’s way is a problematic one. By avoiding a safe and effective vaccine, he exposed his children to a disease that causes discomforting, if temporary, effects and places his children at risk of future disease if the virus is reactivated. For me personally, what tipped my thinking on this issue was this point, that the children will be carrying out the virus for the rest of their lives when such exposure could have easily and safely been avoided.