by Thibaud Haaser, MD, PhD

The current coronavirus pandemic challenges health care systems, raises ethical questions about health policies, and makes some countries fear or even face dilemmas over the allocation of scarce resources. One of these challenges is the responsiveness and adaptation of research to a dynamic context. Vaccine or treatment studies are emerging as priorities as they have a crucial role in the healthcare response. Of course these processes require patient enrollment in order to study the safety and efficacy of preventive or curative strategies.

Research consent is based on fundamental principles such as disclosure of information and voluntariness of participants. The current pandemic must not relax ethical practices of full disclosure of information about procedures, risks and constraints for patients (disclosure must also include the imperative of an understanding of information). Patients’ clinical status may impair their ability to fully understand informed consent documents in a critical clinical situation, but procedures such as family member or deferred consent or even consent waiver are possible ways of dealing with this problem.

Voluntariness could be more problematic in the current context of pandemic. First, the COVID-19 pandemic is a real crisis challenging medical and scientific communities. As health systems are or may be overwhelmed, priority could be to avoid dilemma and difficult issues as allocation of scare resources. Finding treatments seem to be so essential that all patients should be included in research protocols. The collective imperative to have curative and preventive options against COVID-19 would be the ethical justification of such a proposal. Moreover, there are no standard treatments for this emerging infectious disease, so there is no loss of chances. If research protocols are scientifically consistent and approved by a Research Ethics Committee, one could morally justify a proactive and systematic inclusion of patients in clinical trials. Facing a genuine threat of scarcity of medical possibilities, people who can benefit from treatments could have the reciprocal obligation to participate in clinical trials. At patients’ scale, consent could above all be perceived as a compulsory duty towards a community in crisis and no longer as an isolated freedom to say no. A kind of social pressure could weigh on patients so that any refusal to participate could lead to strong feelings of guilt.

Second, the current promotion of health professionals must also be taken into account. Their dedication, bravery and selflessness are remarkable. Around the world, they appear as modern heroes involved in a war against viruses. The problems of dual role consent have already been explored but in addition, their promotion as heroes can influence the possibility for patients to refuse or withdraw their consent to research: it is not easy to say no to a hero. The renewed prestige image of health professionals strengthens existing power relationships between patients and physicians, and also increases the risk of influencing patients’ decisions.

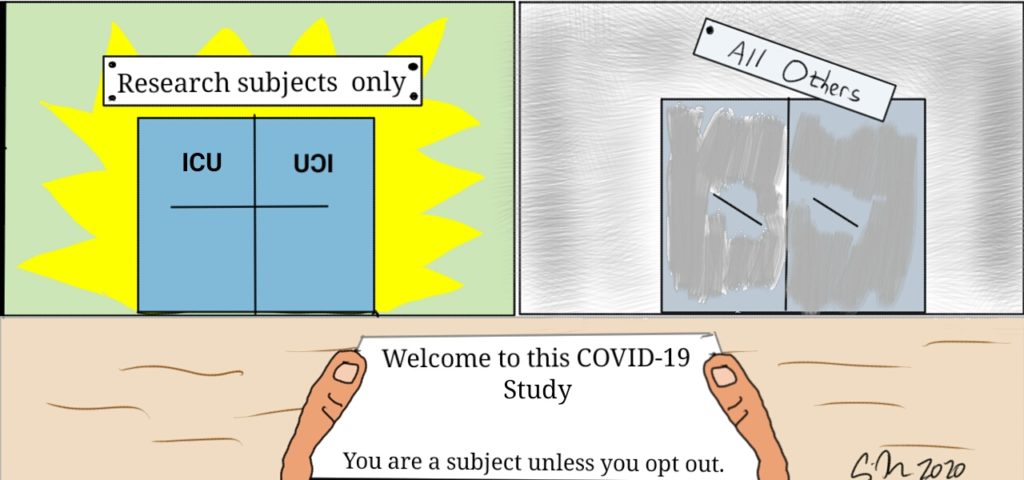

Third, consent to research could be rewarded in the event of ethical arbitration regarding the allocation of scarce resources (such as intensive care beds or mechanical ventilators). The principle of reciprocal obligations is mentioned: an adequate response to their commitment is to take it into account when the clinical parameters are equal with other patients in a situation where allocation choices are mandatory. If the financial reward is fairly common in biomedical research, and especially for healthy volunteers, it is essential to highlight an actual change. Consent to research leads to the idea of participating in a global effort to improve knowledge and therefore for a global benefit. For patients, it is also an opportunity to find personal benefits: Therapeutic benefits (in the case of studies for the development of vaccines or treatments), psychological benefits (feeling of usefulness, sublimation effect) and sometimes financial benefits. Assuming that the reward for participation can be priority access to ICU brings a new dimension of benefit: It is competitive one. The classic motivations for consent are no longer valid, because the first reason for consent to research can only be this “skip the line” effect. Participants can consent more to an increase in their chances of survival than to research.

The crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic requires a global mobilization of research which ultimately leads to the need for a large mobilization of volunteers. The ethical frameworks of biomedical research must imperatively be respected, even in an emergency context. But faced with an unexpected crisis, we must change our outlook on research consent. Thus volunteering can be shaken up, influenced or even questioned. Those effects are more or less motivated or identified but they do change one of the fundament of research consent. It is essential that biomedical researchers pay attention to these changes in order to constantly respect patients’ autonomy and to continue to consider them as ends and not only as means.