by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

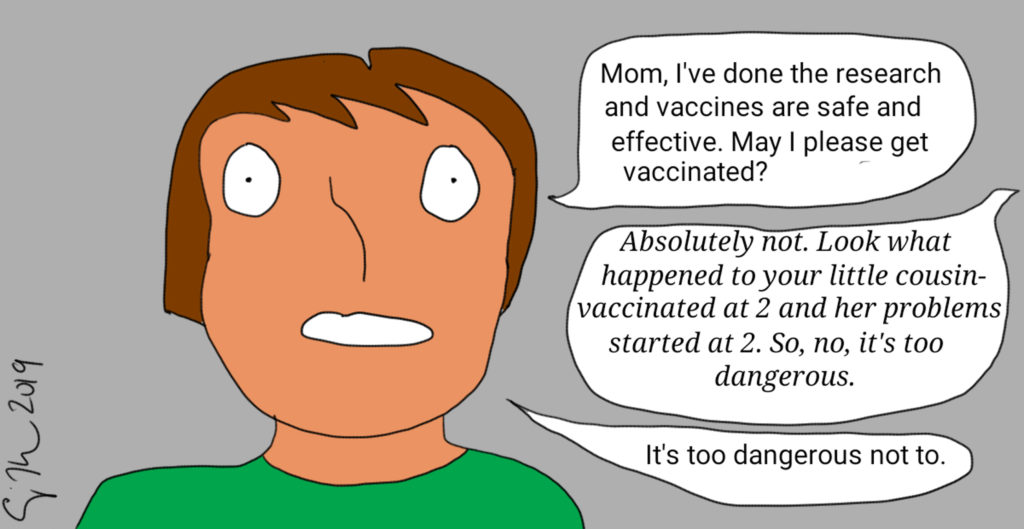

A teenager comes to a medical clinic and asks for an MMR vaccine. Although this particular vaccine is usually given at 12-15 months of age with a second dose at ages 4-6 years, this 16-year-old has never been vaccinated. His parents believe that vaccines cause autism* and are dangerous, therefore they have never vaccinated their children. In the age of the internet, the teen has done a lot of research and found that the science is conclusive: Vaccines are safe and beneficial (as long as you are not allergic to the ingredients). His mother refuses to change her mind. What do you do?

A similar story has played out on Reddit through the journey of Ethan Lindenbergerof Norwalk, Ohio. His school teachers talked to him about vaccination and he learned that most of his classmates had been inoculated. Ethan went online and discovered that all of his mother’s reasons against vaccinations had been debunked. Ethan talked to his mother who refused to change her mind or give him permission to get vaccinated. When he turned 18, he was vaccinated.

With the current measles outbreakin Washington State, more teens are investigating how they can be immunized, going around their parents and straight to the internet. They are learning about the importance of herd immunity. They read about the discredited paper written by Andrew Wakefield. They see studies showing no connection between developmental conditions and vaccines.

His mother’s response is not surprising as the percent of parents who believe vaccinations are very importanthas declined over the last decade from 82% to 71%. As a result, there has been an increase in the number of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaksthroughout the world. Epidemiologists have found a direct correlation between vaccination hesitancy and outbreaks(lower vaccination levels increases outbreaks).

CONSENT

In general, parents get to make the medical decisions for their children, and parental (guardian) permission is needed to receive medical treatment (except for emergencies). So how can a teen decide in favor of a basic public health preventive if their parents will not consent? The answer differs from state to state. In most states, there are certain medical conditions and treatments for which minors do not require parental consent. For example, in all states, minors can consent to sexually transmitted infection treatment. Eighteen states permit doctors to notify the parents, but such a step is not required. Thus, an argument could be made for the teen to consent to a vaccination against sexually transmitted infections such as HPV. This does raise the question of “what is a teen” and how young is too young? In some states there is no minimum age but in others, the teen has to be 14 or 16.

Some states have carved out minor consents, meaning children over a certain age (12, 14, 15, or 16) can consent for substance abuse treatment, mental health care, or birth control. A few states even permit a minor to consent for abortion. In states without these carve outs, there is usually a judicial bypass, meaning a teen can go to court and request that the judge allow the teen to have the procedure. This can be on a one-time basis – a child who wants cancer treatment even though the parents do not believe in Western medicine. Or it can be broader–A judge can declare that a person is a “mature minor” who has the “maturity to make independent decisions”. Even more broadly, a minor can pursue emancipation from their parents. Lastly, in an emergency situation, consent may not be necessary to assess, stabilize, and transfer a minor in the event of a medical emergency.

EXEMPTIONS

With an increase in the number of preventable disease outbreaks, more states are passing laws to limit vaccine exemptions to be only for medical purposes(for example, California, West Virginia, and Mississippi). Other states, such as Illinois, Nevada, Florida, and New York, allow documented religious exemptions in addition to medical. Eighteen states permit medical, religious, and philosophical exemptions. The latter simply requires a parent to say that they “do not believe” in vaccines or that they have a philosophical reason for avoiding their children’s vaccination.

ANALYSIS

One method for considering a bioethics case is to use analogy. In this situation, that could be (1) when a parent refuses treatment for a child who also does not want the treatment; and (2) sometimes the child wants a treatment but the parent refuses. Consider the first case, a

parent refuses medical treatment for a child with a life-threatening illness. In many of these cases, the hospital or the state goes to court and requires the child to have treatment. A few years ago, a mother lost custody of Cassandra C, her 17-year-old child, for going along with the child’s request to refuse cancer treatment (with a high success rate). The mother was not permitted to see her child during the time of treatment and the child lived in a medical facility the whole time. A few years earlier a Utah case was brought against parents who fled the state to prevent their child, Parker Jensen, from receiving court-ordered cancer treatment. When he became sicker, they returned for treatment. The reasoning in all of these cases was that the state has a vested interest in the welfare of children including in receiving medical treatment. The doctrine holds that children should have the standard of care for their disease.

Another analogy is when a child wants treatment and the parent does not. For example, a child needs a blood transfusion but their Jehovah’s Witness parents are against it. In such cases, it is common for the hospital to go to court for an order permitting them to administer treatment, even against the parents’ wishes. The courts often reason that the child may not choose the same religion as an adult and that the state has an interest in the health of a child. However, these cases tend to focus on life threatening situations where the alternative to receiving blood is death. While the alternative to a vaccination is a highly increased likelihood of morbidity, the analogy is imperfect in the immediate threat to the patient’s life. If a child dies from not receiving a transfusion that poses no threats to others, whereas not vaccinating does threaten others. Closer is when a child may want to take androgen blockers because they are transgender—a child cannot receive these without a parent’s permission.

In a vaccination situation, the minor does not have a disease, yet. Perhaps the state interest extends beyond making sure children receive a standard of care to treat a current life threatening disease to prevention of communicable diseases in the first place. Public health is a government function and under U.S. law has police powers. Public health officials can require a person exposed to a disease be quarantined. States have the authority to require immunizations before children attend public school (and can also grant exemptions to these requirements). Thus, one could argue that the state’s interest in protecting children includes giving them the proven tools of medical science to prevent disease.

Lindenberger has opened a window on to a new bioethical issue—when children want medically and scientifically safe treatment for preventive disease and to protect the public’s health. I would put forward that given the state interest in protecting children and in protecting the public welfare, that states embrace carve out exceptions that allow minors (of most any age) to consent for vaccination even if parents disagree. More immediately, there should be easy access to judicial bypass that will allow minors to get vaccines even in the face of parental opposition. Third, states should follow California’s lead (and Washington’s recent bill) to only permit exemptions for medical purposes.

With the increased availability of scientific information on the internet where facts and claims can be easily checked, the children of anti-vaccine supporters may increasingly be asking for an intervention that we generally require of all children. They should be allowed to get it.