by Keisha Ray, Ph.D.

“Nothing about us without us.”– J.I. Charlton, adopted by disability rights advocates

Recently I sat in a room of scholars who teach health humanities in medical schools and undergraduate institutions across the United States and Canada. At the top of the list of topics we discussed was the power of health narratives as pedagogical tools. Patients’ stories of illness, treatment, suffering, and healing were shared, read, dissected. Some participants even shared their own health narratives. But much like educators teaching health humanities across North America, the room of 35 or so participants were overwhelmingly white, upper to middle class, able-bodied, cisgender, heterosexual, and very well educated possessing doctorate and medical degrees. Yet the people in the stories we were discussing did not represent who we (mostly) were as a group. Most of the stories were about economically poor people, people with disabilities, LGBTQ people, African Americans, and Native Americans. While I acknowledge the power of health narratives, especially as pedagogical tools in the classroom, tools that I too have used in my own bioethics courses, I couldn’t help but ponder our privilege and how much our status contrasts with the people we are discussing. As we are sharing other people’s stories and using them as lessons in the classroom we owe it to our students and to the people in these stories to think about who is allowed to tell marginalized people’s stories. What precautions should we take to make sure that people remain the owner of their stories?

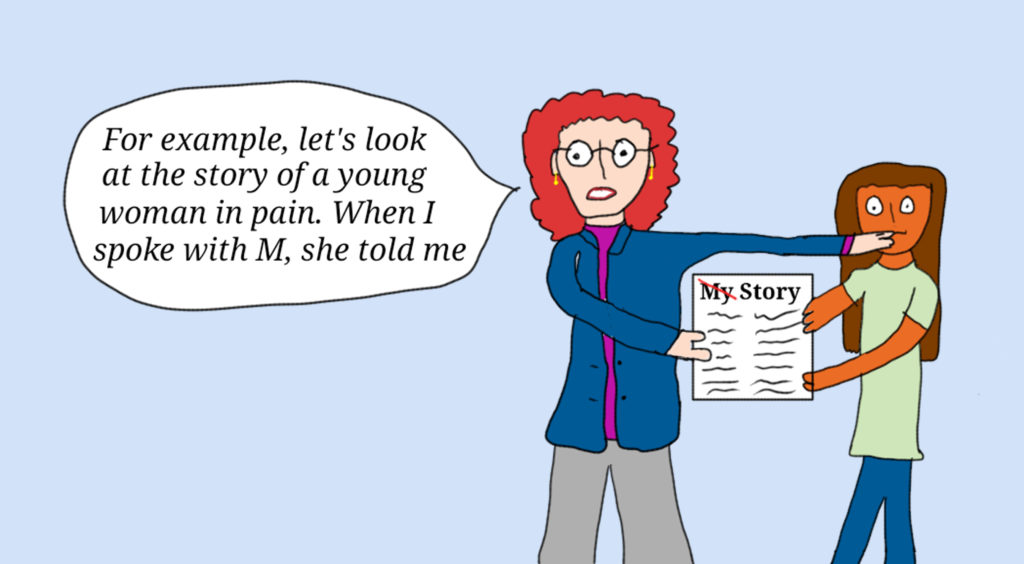

Many of us in our health humanities and bioethics courses frequently tell the story of Henrietta Lacks, a poor, black woman whose cells were taken without her knowledge but whose contribution built much of modern biology. Many times we tell her story to caution future physicians and nurses from taking physical parts of patients without their knowledge. Many of us, like myself, also use the story to highlight the differing levels of privilege that can exist in a patient-doctor relationship, which warrants extra precautions so under-privileged patients aren’t taken advantage of or feel misled about their care. We teach these lessons to our students yet we have no problem taking the stories that belong to patients and using them for our own purposes. Why are we troubled by the idea of taking someone’s physical self but embrace the taking of someone’s storied self? We are concerned about the use of Lacks’ cells but not that those who have recorded and told her story profit off of the narrative. Because of differing levels of privilege between those telling the stories and the subjects of those stories, we as privileged educators have greater than normal responsibilities when telling their stories. One of those responsibilities is to make them active figures in stories rather than no-name faces whose stories have been hijacked.

One way to make patients active in their own stories is to get their permission to tell their story. This may seem obvious, but I have been in many lectures in which a white person has told the story of African American patients and did not mention whether their permission was given. It is possible the presenters just forgot to mention they had permission from the patient, but this should be a priority and not something with which to be careless.

Also, we have to be as open and explicit as possible about the settings in which we will tell their stories and how often we will tell their stories since often their stories may be a part of presentations that we give at multiple conferences, invited lectures, workshops, teaching demos, etc. We must also try to anticipate some of the comments, including criticisms that listeners may offer and prepare the subjects of the stories for people’s reactions because those reactions could very well get back to them.

If we are using any type of media to present the stories, such as PowerPoint slides, we also have to consider that listeners may take pictures of the PowerPoint slides and post them on social media sites like Twitter or Facebook where they can be reposted many times. If we use hard copies of stories, listeners could disseminate those copies to people other than those in the original audience. Once we present someone else’s story we have lost control of who hears the story and how those who hear the story choose to re-present the story to the world. This means that the stories could be used in malicious ways or to support arguments we did not intend. As I have mentioned, this could get back to the subject of the story and cause distress, cost them employment, harms to their family and other adverse events. These are all possible outcomes of telling people’s stories that they may not have thought about. To give patients more control of their own stories we have to get their permission to use them and make patients aware of these possible adverse outcomes as best we can. This is especially important given medicine’s poor history with these populations of people. We have to take these steps so that we don’t add to this poor history and instead continue to work to change the long term effects taking others’ stories has had on medicine’s relationship with marginalized populations.

We should also make efforts to accompany stories with the voices or the visuals of the subjects, if they want to be known. If it is a popular story in print we can accompany the story with photos and biographies of the patient to help listeners situate the story as a part of a person and a part of a community. Additionally, we can ask patients whose stories we are sharing whether they would be interested in recording part of their story and making sure to include that in our presentation of the narrative. This may also make patients feel like they have more ownership of their story. For students, audio or visual recordings can send the message that the story has a face that is attached to a real person that is worthy of our gratitude for allowing us to learn from their experiences. However, including a recording of the patient risks the patient being identified. This is particularly true if the story and any accompanying recording is shared online. For this reason, we should make patients aware of this risk and if they want to remain anonymous we should not push them, but we should at least give them the option to be attached to their story, an option that perhaps they did not think about. Overall, it’s about being as honest as we can with patients. Rita Charon, who has written multiple articles on narrative medicine argues that physicians have to find a way to have honest and open conversations with their patients and using stories is one way to do this. But honesty and openness must continue when the act of storytelling has ended. An open and honest conversation must include what we will do with the story and how it may affect patients so that sharing the story doesn’t add another chapter of pain.

People with any combination of privileges—white, able bodied, educated, economically secure, cis-gendered, and straight—are the bulk of health humanities and bioethics educators; thus, they will be the majority of people telling marginalized patients’ stories. If we don’t tell these stories, it is very possible that these important and moving narratives won’t be told. But we cannot take this task lightly. We do not want to alienate patients from their own stories and we do not want to further marginalize already marginalized communities. We are telling these stories because we want medicine and health care to change. We are telling these stories because we want medicine to treat these people better and we believe that if we share these stories with students they will be better facilitators of health care. So if we are lucky enough to be given the opportunity to tell these great stories we have to acknowledge our privileges that put us in a position to tell these stories and make sure that the subjects of these stories remain the owners of their experiences.