by Dani Shapiro

Two and a half years ago, after whimsically submitting my DNA to Ancestry.com for analysis, I made the discovery that the father who raised me – the long-dead father I adored – had not been my biological father. I could easily have never known this. I could have lived my entire life not knowing the truth of my paternity.

As I stared at the results on my computer screen, as I saw a match with a first cousin who was a perfect stranger, as I scanned the list of unfamiliar names to whom I was apparently related, I quickly understood what had happened. I recalled a long-ago conversation – the only conversation – I’d had with my mother, in which she’d let slip that she and my father had difficulty conceiving me and had gone to an institute in Philadelphia where a world-famous doctor (her words) had developed a test to monitor a woman’s ovulation. She then told me that my father would be called when she was at the peak of her ovulation, and he would drop everything and race to Philadelphia from New York, where he worked, so that the procedure could be done.

The procedure was artificial insemination, and the story was that my mother had been inseminated with my father’s sperm. I was conceived in 1961. I later learned in my research that there had been a common practice of mixing donor sperm with those of the intended father. I learned that parents would have been told this was a “treatment” to boost the father’s chances. That couples would have been told to have sex, come in for the treatment, have sex again – and that way they’d never really know the true paternity of the child. I’ve learned that, at least at The Farris Institute for Parenthood, where I was conceived, once a woman became pregnant, she might be told that the timing of her results indicated she must have already been pregnant before donor sperm was introduced, further creating a false sense of certainty that the husband was the biological father. Even if a father was completely sterile, Dr. Edmond Farris would never tell him. Great lengths were taken to protect the father’s ego, as well has his bond with the child. Infertility, especially male infertility, was shameful and kept secret. One thing, however, seemed perfectly clear: the child would never know.

I am that child. I grew up to become a writer, a wife, a mother, a teacher. At the time of my discovery about my paternity, I had written nine books: five novels and four memoirs. The theme of much of my work, both as a novelist and memoirist, was family secrets and their corrosive power. I often tell my students that “theme” is just a fancy literary term for “obsession.” You might say that secrets obsessed me. I knew, in some deeply buried, subconscious, powerful way, that there was much I didn’t know. As a child, I felt different, other, like there was something “off” – something I couldn’t quite put my finger on. My nine books reveal a trail of breadcrumbs in this regard. In my first novel, which was a thinly-veiled bildungsroman, my young narrator longs to resemble her father’s family. In my memoir about the writing life, Still Writing, I write about snooping through my parents’ things: “What was I searching for? A clue. Areason.”

In light of what I now know, it has been fascinating, and somewhat disturbing, to look back through my own work and realize just how close this knowledge was to me – and yet, at the same time, how far away. I came across a psychoanalytic concept, “the unthought known,” first written about by Christopher Bollas, in which he describes that which we know, but cannot allow ourselves to think.

I was a blonde, blue-eyed, fair-skinned child, prone to blushing. My father’s family – Jews of Eastern European Ashkenazi descent – were dark-eyed, olive-skinned, with distinctly Semitic features. All my life, I was told that I didn’t look Jewish. I was told this so often that it became formative – a part of what made me me. I was the Jewish girl – raised observant, in fact – who didn’t look Jewish. When people said it, I now understand, they were seeing something I was unable to see myself. It made me uncomfortable, though I didn’t know why.

The secrecy that seems, to me, at the foundation of reproductive medicine at the time of my birth – and that to some degree persists to this day – is the most problematic and toxic part of the experience of discovering as an adult that one has been donor-conceived. It isn’t the fact of it, but rather, the hiddenness. In the pursuit of a child, the child ceased to be real. Doctors and hopeful parents colluded, certain that because the child would never know, it therefore didn’t matter.

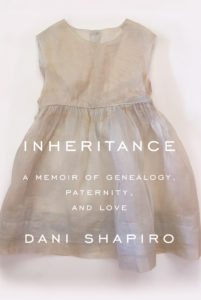

As of this writing, I’m on a nationwide book tour for Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love. I’m speaking to large crowds about my experience, as well as the research I’ve been doing for the past couple of years, since my discovery. One thing is already clear to me: interest in this subject is tremendous, and so is misinformation. I was recently a guest on a call-in radio program in Philadelphia, and several men who had once been sperm donors wrote in during the hour to say that they didn’t plan to ever submit their DNA to a commercial testing company because they didn’t want their biological children to come looking for them. I was in the position of having to break the news to them that they are most likely discoverable whether or not they’ve spit into a plastic vial themselves. Now, there are no more secrets. What will this mean for the future of anonymous donation, or the question of disclosure, or the possibility of a registry of donors in this country, and regulation? Since the recent publication of an essay I wrote for Time Magazine, in which I outline some of these quandaries, I have heard that some parents of donor-conceived adults who had never disclosed the truth to their children are now facing a terrible decision: do they tell their grown kids about the secret that they’d kept? Or do they live with the awareness that their kids are likely to find out – very possibly after their parents are gone?

As of this writing, I’m on a nationwide book tour for Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love. I’m speaking to large crowds about my experience, as well as the research I’ve been doing for the past couple of years, since my discovery. One thing is already clear to me: interest in this subject is tremendous, and so is misinformation. I was recently a guest on a call-in radio program in Philadelphia, and several men who had once been sperm donors wrote in during the hour to say that they didn’t plan to ever submit their DNA to a commercial testing company because they didn’t want their biological children to come looking for them. I was in the position of having to break the news to them that they are most likely discoverable whether or not they’ve spit into a plastic vial themselves. Now, there are no more secrets. What will this mean for the future of anonymous donation, or the question of disclosure, or the possibility of a registry of donors in this country, and regulation? Since the recent publication of an essay I wrote for Time Magazine, in which I outline some of these quandaries, I have heard that some parents of donor-conceived adults who had never disclosed the truth to their children are now facing a terrible decision: do they tell their grown kids about the secret that they’d kept? Or do they live with the awareness that their kids are likely to find out – very possibly after their parents are gone?

Ultimately, I believe that it’s a fundamental human right to know our identity – to know where and who we come from, and, failing that, to know that we are missing information. Certainly, there are many adoptees and donor-conceived people who are unable to find information about their biological origins. But what’s essential is that they know that there’s a missing piece. They don’t confidently offer incorrect medical history for themselves, and their children, as I did all my life. They don’t wonder why they are sometimes suffused by a sense of longing and otherness, known in adoption literature as “genealogical bewilderment.” Because they know what they don’t know, in a way, they are able to reclaim their identity and absorb the missing pieces.

But for those of us from whom secrets have been assiduously kept, we have spent our lives feeling our way around in the dark, our sense of ourselves slightly askew. We have been formed by those secrets, even without knowing them. People sometimes ask me now if I wish I had never found out – if I had never spit into that plastic vial. And my answer is a swift, resounding no. I’m enormously grateful to know the truth of myself. It adds dimension and perspective, and answers questions I’ve been asking, in one way or another, all my life.