by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

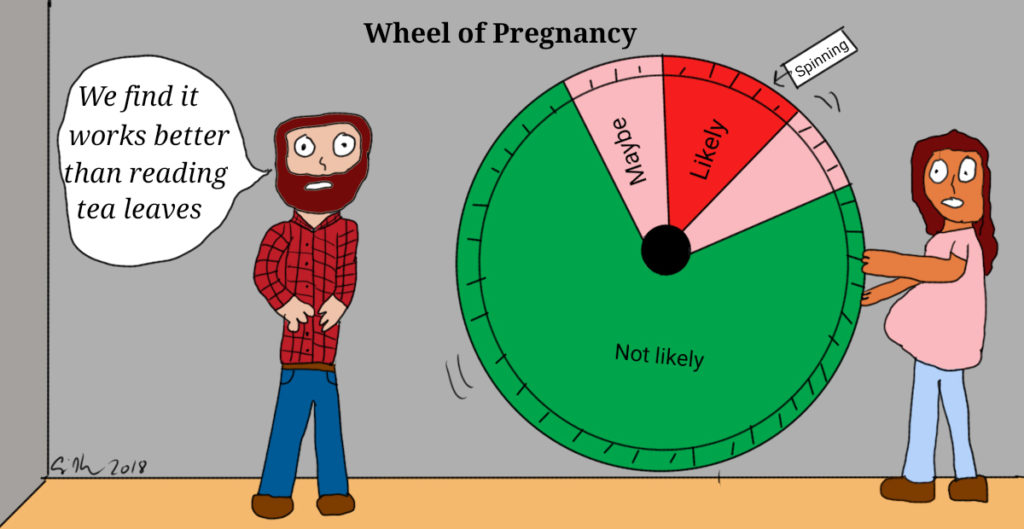

“What do you call a couple that practices the rhythm method?”

“Parents”

This old joke is getting a modern twist as the FDA approvesNaturalCycles, a mobile app for charting fertility and determining what days are safe for sexual activity with a low risk of conceiving. According to the NaturalCycleswebsite, a user (i.e. a woman) takes her temperature everyday (using a special device) and that information is recorded in the app. She also records her menstrual dates. Using “a smart algorithm”, the app tells you what days are safe for having (unprotected) nonreproductive sex. The app service costs $79 per year (or $9.99 per month) and has over 900,000 users worldwide. The website goes on and claimstwo clinical studies showing thatit is 93% effective.

The studies, however, lead to many questions. The first study, in The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care,is based on “retrospective analysis”, a method that requires accurate record keeping by the app and by the user. Subjects were recruited from a list of users registered during a 6-month period, who responded to “conventional end-consumer marketing techniques”—i.e., people who answered an ad. It also did not have a comparison group that used another form of birth control (or none at all, though that would be ethically problematic). The second study appeared in Contraceptionwhere the authors concluded “This study shows that the efficacy of a contraceptive mobile application is higher than usually reported for traditional fertility awareness-based methods.” The comparison group is people using other forms of charting rather than against people using hormonal or barrier birth control? In the fine print, the paper states that 54% of women who began the study, dropped out in the first year and there is no follow up data as to why (Perhaps they became pregnant? Or the method was too difficult to use? ). Another problem with the study is that not all of the subjects recorded their sexual activity (The company thought asking such questions would be “intrusive”). In fact, half of the pregnant women recorded no sexual activity. The analysis also did not take into account women’sage (decreasing fertility) or by whether they had regular or irregular menstrual cycles.

These results are problematic because of poor sampling techniques and problematic analysis. The claim of 93% effectiveness in a highly curated sample is hard to believe when “fertility awareness based methods” has a 76-88%success rate, which is lower than barriers or hormonal approaches. Two factors come into play here: The success of this method relies on people having meticulous measuring and recording habits; ignores that sperm can remain viable for up to 3 days after intercourse; and does not account for the fact that not everyone follows a standard body temperature change—stress, travel, sleep patterns can all affect basal temperature.

Studies of other similar apps (and devices) have also been found wanting. The Daysy system works much the same way as NaturalCycles. One difference is Daysy says it is about tracking fertility rather than preventing pregnancy. It also has a study to show its effectiveness: “It seems that combining a specific biosensor-embedded device (Daysy), which gives the method a very high repeatable accuracy, and a mobile application (DaysyView) which leads to higher user engagement, results in higher overall usability of the method.” “It seems” is hardly scientific language. The study used user self-reports from an invitation sent to registered users (hardly a scientific sample). In fact, a commentary criticized the study for its flawed data collection methods and analysis which “produced unreliable estimates of contraceptive effectiveness” and recommended that the study paper be withdrawn by the journal.

Why wouldn’t these companies do comparison or other well-designed studies? After all, for clinical trials, one must compare against placebo (and one could not ethically give a placebo to people who are trying to prevent fertility) or against another proven, effective method. Neither were done here because the FDA does not require medical devices to meet the same standard as pharmaceuticals.

NaturalCycles and Daysy are not the only birth control apps on the market: There are nearly 100 of them. More than half of them say they should not be used as birth control. Meta studies looking at fertility awareness-based methods apps have found that “Studies on the effectiveness of each fertility awareness–based method are few and of low to moderate quality.” In another study rating effectiveness of these apps, the authors concluded that they “may not be sufficient to prevent pregnancy.”

In fact, this week a Facebook ad for NaturalCycles was banned as misleading after UK investigators found the ad’s text exaggerated the effectiveness of the app. Another investigation began when a Swedish hospital reported 37 unwanted pregnancieswith the app. Investigators found that claims of pregnancy prevention were based on “perfect use” of the app which occurred only 10 percent of the time. Devices should have to undergo “human factors testing”—meaning that the device can easily and properly be used by the average person. By using a retrospective analysis, this step was not done, or at the very least, not publicized.

This approval raises several ethical issues. The FDA is looking at its processes for approving digital health, at a time when the number of such apps and programs is booming. Perhaps there should not be a lesser standard than there are for pharmaceuticals, especially when a life changing event may be a side effect. Certainly the use of flawed studies should not be a basis for approval.

Second, from a critical feminist perspective, these apps further the myth that birth control is only the concern of a female partner. Consider NaturalCycles website in pink and purple: The only pictures on the site are of young women (okay, there is one picture with a male model in it and a second picture featuring a male co-founder of the app). The thermometer and the app are purple and white. The not-so-hidden message is that birth control is a women’s issue. Interestingly, the health care professionals information page is in blue: Perhaps a bias that the prescribing (recommending?) health care provider would be male?

Third, from a critical race perspective, of the many pictures on the website, only two include a woman of color. In one image the woman of color appears alongside two women who appear white. Of the multiple images featuring a lone woman, only one has a woman of color. Both of the men who appear on the site appear white. The lack of representation is concerning because national data show the rate of unintended pregnancies are highest in women of color.

Fourth, published analyses of these products suggest that women should work with a health care provider to learn how to use fertility awareness-based methods properly. But, should a health care provider be recommending a method that is less effective than other methods? The provider should probably encourage a patient to use birth control methods with better proven efficacy. However, if the patient insists on using an app or other fertility tracking system, then helping the patient to use it well may be better than having them use the app without guidance.

Women may have several reasons for using a natural tracking method: Religion, pressure from her partner, not wanting to put chemicals in her body, side effects from other methods. Like all health-related choices, women should know the risks, benefits and alternatives. Unfortunately, the information provided by the companies has been shown to be misleading. The lack of accurate information violates autonomy. In approving this program, the FDA may have made a mistake.