by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

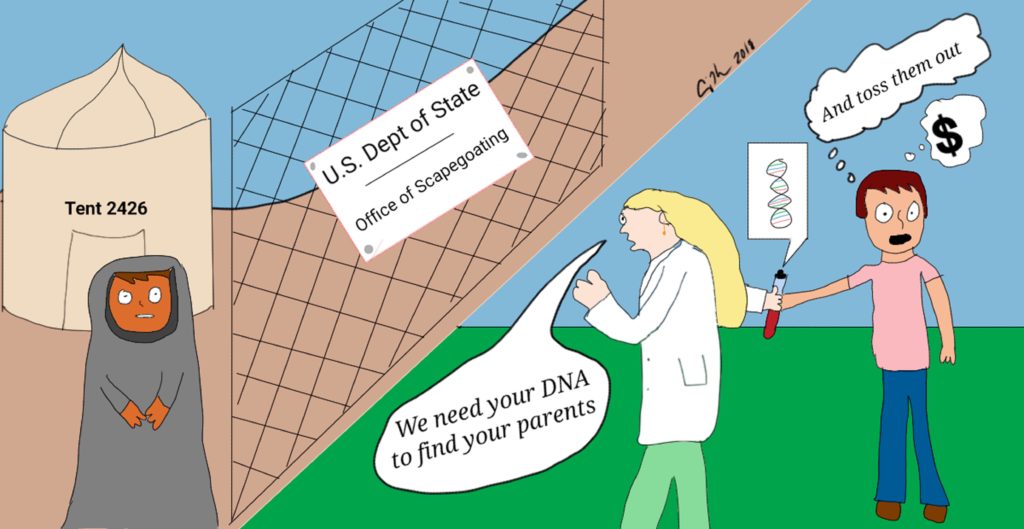

In late August 2019, BuzzFeed reported that, “The Trump administration wants to enable Customs and Border Protection officials to collect DNA samples from undocumented immigrants in its custody”. The information would then be uploaded into NDIS, the national DNA information system run by the FBI. This followed a pilot project begun in May 2019 to take DNA from people at the border in order to see if claims of familial relationships between adults and children were accurate. Their goal was to refer for prosecution when adults lied about being the parents of children asking for asylum.

However, collecting DNA of people detained under the Department of Homeland Security is not permitted under the DNA Fingerprint Act of 2005 and in a subsequent DHS rule (2010). This act allows for other agencies to take DNA samples from people in their custody though. It is this law that the administration is attempting to override with a regulation appearing in the October 22, 2019 Federal Register. The new rule would “require DNA-sample collection from individuals who are arrested, facing charges, or convicted, and from non-United States persons who are detained under the authority of the United States”. The new rule is expected to affect the nearly one million immigrants and asylum seekers who cross a U.S. border annually.

The administration’s stated goal is to help solve crimes. Such a statement is an effort to create a moral panic by equating being an immigrant with violent criminals. In a moral panic, a group is verbally and metaphorically associated with an already reviled and stigmatized population to make people feel disdain for the original group. In this case, the proposed rule connects immigrants with violent crime. The facts demonstrate that (documented and undocumented) immigrants commit far fewer crimes than native-born populations. This data was compiled by the Cato Institute, a group associated with libertarian and conservative interests. The rule is an attempt to further institutionalize racism and fear.

Thirty states and the federal government have laws that permit the taking of DNA from arrestees. Other states permit DNA to be entered into NDIS only upon conviction of a crime. The new program is estimated to cost $13 million and will add approximately 1 million records annually to NDIS’s current 14 million. One of the problems with NDIS is that it disproportionately contains records of people of color since those populations are more likely to be arrested and convicted. Overcoming this bias in the records is the only valid reason for searching commercial DNA databases (which are more likely to contain information from people of European origin). Adding the immigrant information would, however, increase the imbalance since immigrants from Spanish speaking and Muslim-majority countries are far more likely to be detained than from anywhere else.

Forcing someone to give a DNA sample is a clear violation of autonomy. Even if the process is presented as a “request”, it is not an ask that can be refused. In a medical setting, patients would have to give informed consent before giving a sample and having it tested in a medical lab. They would be told the risks, benefits, alternatives and have a chance to give their permission or to withhold it. Even with a commercial DNA company, which is strictly DNA for entertainment and falls under a user agreement (rather than informed consent), the customer has an opportunity to read the documents to which they agree (not that anyone ever reads the near 50 pages). But in a detention center, detainees likely won’t have access to either informed consent or user agreement processes. Even if they did, the chances are slim that the information would be offered in their native language. The companies and laboratories who get the contract for analyzing these samples should refuse to do so since the samples are given under duress. Employees of these labs (even if it’s the FBI’s own lab) should refuse to do run the analysis for the same reason. Sometimes, we need moral courage.

This requirement is also a clear violation of privacy for the person who is forced to give the sample, but also for people who have not been detained. As I have written here before, when you share your DNA, you are also sharing information about your 300 closest relatives. When information is collected from detained immigrants and asylum seekers, it becomes easier to find their relatives who may be in the United States. Connecting DNA to a family and finding individuals is a fairly simple process that researchers have done multiple times. Thus, it is possible that this information will actually be used to find extended families and detain them. (Other arguments have laid out ethical guidelines for using the DNA of detained children for purposes of reunification. The current proposal violates many of the precepts).

Another concern is that DNA analysis and identity matching is an inexact science. Sure, a person (unless they have an identical twin) has a unique DNA, but they share major portions with their near relatives. There are large issues with how labs handle and test DNA ranging from sticky DNA that can pollute samples, to a lack of regulations on how to avoid contamination, and secondary DNA transfer. There are problems with the DNA identification process and industry that should raise serious issues about using DNA databases to identify people, their family, and match them with criminal activity (or mark them for detention). In addition, we have to consider that just because DNA is found at a crime scene does not mean a person committed a crime—it simply means that at some point in the past they may have been at that location (perhaps years before the crime took place). A 2018 study showed how inaccurate this technology and its implementation can be: “DNA mixture interpretation, as can be seen from this study, is a complex area. Variation in the chemistries, analytical approaches, and software to interpret inevitably lead to variation across participating laboratories.” In other words, the complexity of the process means different labs end up with different findings.

Some proponents have suggested that collecting DNA is simply fingerprinting and is no different than collecting biometric data. After all, when a person leaves or enters the U.S. through 23 airports and 6 cruise terminals they give a facial image under the Traveler Validation Service. Customs and Border Protections (CBP) also collects fingerprints at most ports of entry and whenever someone applies to the TSA PreCheck or Global Entry programs. However, under CBP’s own privacy policy, the data of U.S. citizens is “deleted within 12 hours of identity verification” and up to 14 days for “in scope travelers” (i.e. non-U.S. citizens). The purpose of this system is not to add records to a criminal database or to create a moral panic. Also, a fingerprint or facial picture does not pose privacy problems for other relatives. The DNA proposal is substantially different than other biometric programs.

This proposal comes a month after the Department of Justice released its interim guidelines for using DNA familial search (not looking for the perpetrator but for the perpetrator’s family). The guidance says that such searching should only be used for violent crime only and only after traditional investigation means have been exhausted.

The bottom line is that forcing detained immigrants to give a DNA sample is a violation of their human rights and only serves to drum up a moral panic. I plan to let my elected officials know my position on this issue. You should too.