by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

I have been thinking a lot about the idea of efficiency lately. About 6 years ago, I was listening Andrew Tarvin, an improv comedy colleague of mine—now professional “Humor Engineer: give a TED-like talk on the notion of “efficiency” as a driver in his life. At the time I thought, “Yes, I resemble that idea.” When people ask me (as they often do), “How do you accomplish everything you do” I always jokingly reply, “I do not sleep much and I don’t have kids.” While those are true statements, the real reason is that I have tried to cultivate an efficient life.

Most people shudder when they hear the word efficiencybecause it has come to stand in for a company doing something that is going to cost us more in terms of time or money. When companies plan for efficiency, it means that they are going to be cutting jobs. When a bank or an airline develops an efficient system, I know that I will be charged higher fees to check a bag, talk to a human being, or visit a teller.

These references have not always been the meaning of efficiency. According to the Oxford English Dictionary,the term has meant “The fact of being an operative agent or efficient cause” (now only used in philosophy); “The action of an operative agent or efficient cause; production, causation, creation” (obsolete); “Fitness or power to accomplish, or success in accomplishing, the purpose intended”; “Efficient powers or capacities”; “The work done by a force in operating a machine or engine; the total energy expended by a machine” (obsolete); “The ratio of useful work performed to the total energy expended or heat taken in”; “an efficiency apartment; a room with limited facilities for washing and cooking” (North American).

The common modern usage, mainly in business, might be defined as “minimizing labor and costs required to deliver a product in order to maximize profit.” Often though, for those outside the system, these efforts seem more inefficient since it requires more effort of the consumer or user—I now have to perform tasks myself that were once performed by company employees. The efficiency in this sense, is only for the company’s bottom line.

The value of efficiency that I have ascribed to draws on the ideas of “an agent of efficient cause” and “success in accomplishing the purpose intended.” I am talking about performing activities with the least number of steps possible. For example, when I am leaving the house to run errands or go to campus, I want to be sure that I have everything I need with me because to forget something means I have to go back for it, or put off a task for another day (or purchase a more expensive lunch than the one I had made). Having to backtrack and take extra steps is inefficient. We have several floors to our house and spend most of the waking hours in the middle floor. When I need to bring things upstairs, I will place them on the stairs and the next time I need to go up the bedrooms, I then bring this accumulation of items. It is more efficient to make one trip, than many.

In my work, when writing a paper (or a blog), I try to have all of my necessary materials before I sit down to write (references, hyperlinks, even my coffee). I may take a break while writing—this does not reduce efficiency—but having tobreak my train of thought to find something not at hand is inefficient. One advantage to this method is that I can write in a coffee house without internet (though if that’s the case I probably will not return) or even on a plane. By the time I sit down to write, I know most of what I want to say. I’ve also trained myself to produce strong first drafts to reduce the amount of editing I’ll need to do later. This is not the undergraduate student believing that their first drafts are masterpieces (they never are), but having worked as a journalist with strict deadlines taught me a lot about efficient writing.

I have been doing this sort of thing since I was kid. Near the end of each school day, I would use my date planner (yes, I have been carrying one around since my grammar school days) and figure out how much time each activity I had to do would take—homework, playing with friends, eating, watching TV—to see how much I could accomplish. I did not think about this as a drive for efficiency at the time, but it was.

There are aspects of bioethics that very much fall into the efficiency framework—things like advance care planning and proactive clinical consultation. As I often tell my students, it’s easier to prevent a problem than have to react to it—Think about the recent case of nondisclosure of serious conflicts of interest by a cancer researcher. Just disclosing in the first place would have been more efficient than trying to salvage his reputation. But so much of our work is completely outside of our control: students, patients, bureaucratic systems (which have a different view of efficiency) seem to always get in the way of our efficient navigation of the world.

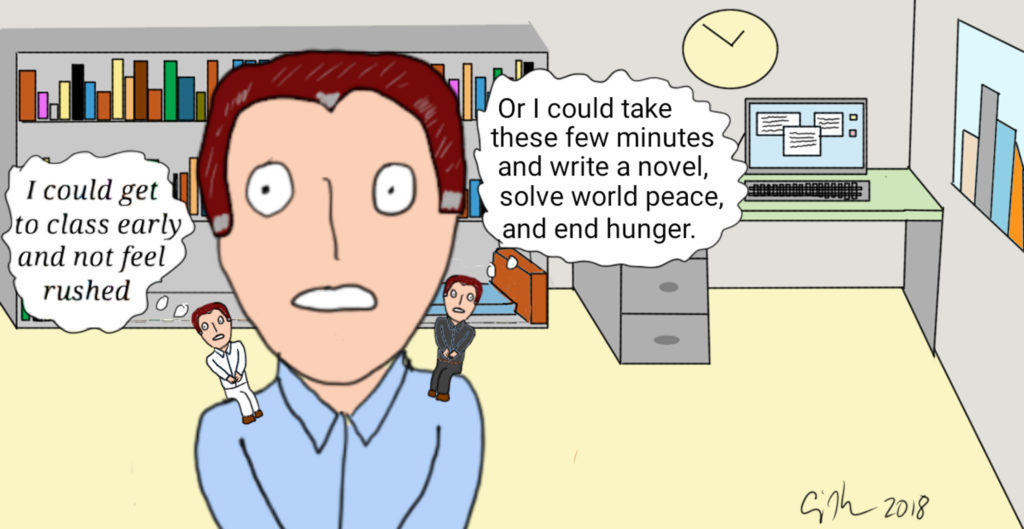

This obsession also has a downside. Sometimes I have difficulty completing tasks that my subconscious has recognized as inefficient. For example, I am terrible about booking airplane tickets and hotels. I have to do my research, pick the flights that will work the best without costing too much and wondering if there’s always something better out there; a process that ends up wasting a lot of time—inefficiency in trying to be efficient. It also means that I rarely show up to a class or a meeting more than a minute or two before it begins. The idea of being in a space where I am not using my time productively, irks me. If the calendar warning goes off 15 minutes before a class, I know that it takes me 5 minutes to get the room. That means I have ten minutes and can try to get something else done in the meantime. Of course, then I feel like I am rushing to get there and diving in immediately without a chance to take measure of the room. But that sense of “wasting time” violates my sense of inefficiency. I wouldn’t even start talking about me view of traffic and stoplights.

What lessons can one take from this discussion? For me, my goal is try to not expect other people to share my value of efficiency and to be forgiving of myself when I am inefficient. For bioethics, it often seems that we are reacting to whatever the latest news item is (and I am guilty as charged). Would it not be more efficient for us to write about ideas and draft guidelines before the events of the real world get ahead of us? What lessons do you think we can learn to have a more efficient bioethics? In what ways would bioethics benefit from being less efficient?