by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

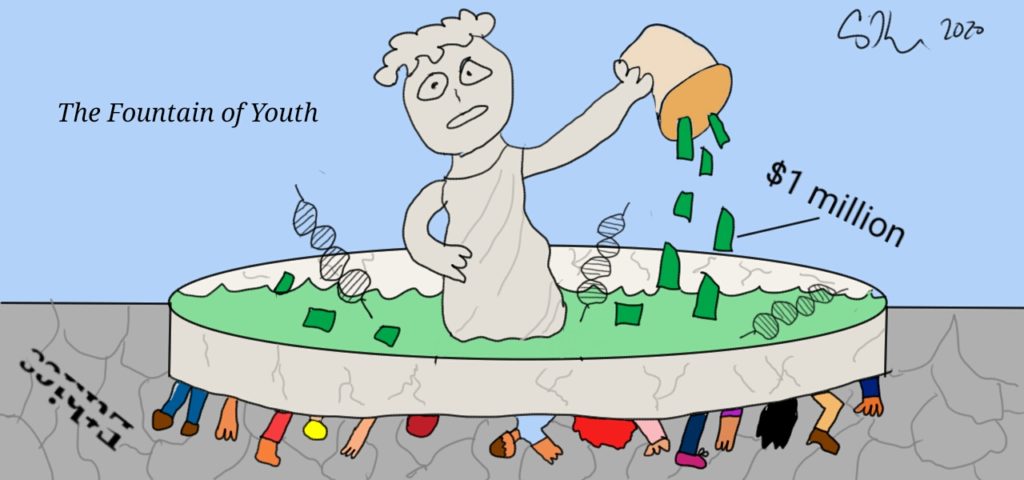

As the legend goes, in the 16th Century, when he was 51 years of age, Ponce de Leon received permission from the King and Queen of Spain to explore the islands north of Puerto Rico to search for the fountain of youth, a fabled spring that would grant eternal life and youth to whomever drank from it or bathed in it. He eventually discovered Florida and the southeast United States.1 Every few years, it seems that the next fountain of youth splashes across the news pages. Extreme calorie restriction extends the life of rodents? While human followers appear to be healthier agers (or were they going to age with more health to begin), results have not shown extended life spans. Then there was resveratrol, the agent in wine that keeps mice alive far longer than their normal lifespan. That failed in humans too. Now, in the 21stCentury, geneticist William Andrews claims that he has found the cure to aging. He has licensed his miracle cure to Libella Gene Therapeutics and they are running clinical trials. The only catch? To be a research subject will cost you $1 million and you have to get to Colombia.

This Stage 1 study will recruit a total of 15 subjects (5 healthy people over age 45, 5 with Alzheimer’s, and 5 with critical limb ischemia).2 Some subjects have already signed on. As you read this post, a 79-year-old person is receiving this treatment.

Andrews says that the cause of aging is the shortening of telomeres, the endcaps on DNA that shorten with each cell division. Andrews figures that if you can lengthen the telomeres than you can not only extend life, but you can return youth. He believes that his telomere lengthening genetic treatment will reverse aging by 20 years: Hair will regain its color, wrinkles will disappear, and vitality will return. Andrews’ goal is nothing less than to cure aging. This seems like a simplistic view of aging which other scientists say has multiple causes beyond genetics such as diet and environmental exposure.

My first issue is the view of aging and death as “disease.” A disease is an infection or a malfunction of a biological system. Aging is a normal part of human life. Being older may not be culturally popular or valued, but that hardly makes it a disease which must be cured. If a condition is part of most living things then perhaps it is part of life. We may not like it, but that does not mean it needs a technological fix. For people who are desperate and view aging as a plague, they may be coerced into paying for this bottle of snake oil.

A second problem is that a new study seemingly disproves the telomere premise. Researchers in Aging Cell (December 2019) examined nearly 380,000 biobank participants in the UK and found telomere length associated with risk of cancer and coronary heart disease, but nothing else: “Telomere lengthening may offer little gain in later‐life health status and face increasing cancer risks.”

Manipulating the human genome is not a risk-free endeavor. Beyond the potential for cancer, the delivery method is problematic. Getting new genes into cells is more often done with viruses (specifically, with virus shells that have their infectious DNA or RNA removed and the edited human genetic material inserted). This process can be dangerous. As a research subject, Jesse Gelsinger died from an immune reaction to the viral vector used to insert corrected genes into his cells. Similar animal experiments have found liver and nerve damage.

Perhaps most disturbingly is that when I pointed this out to Andrews, his response was that he had examined what people did in the past and they had made “stupid mistakes.” He went on to say that all of his subjects would be fine and there would be no adverse outcomes because he would not do anything “stupid”. Essentially, he was saying “trust me, I know better than every other scientist”.

Pay-to-Play

The idea of paying to be a research subject is a fairly new movement in the research world. Most research is funded by federal grants or pharmaceutical and device manufacturers. Also, Stage 1 trials usually recruit healthy subjects and look for safety. The study is titled, “Evaluation of Safety and Tolerability of Libella Gene Therapy (LGT) for the Treatment of Aging: AAV- hTERT”. Efficacy is not sought until stage 2. At $1 million each, will these subjects be satisfied with simply learning if the approach is only safe? For that price tag, a subject might fall victim to the therapeutic misconception—the idea that the research will benefit them. The goal of research is to collect data, not to treat or cure any particular individual. In many trials, a subject may be randomly assigned to receive the new agent or a placebo. Would someone be okay with paying $1 million for a placebo? My guess is they would not.

The notion that a person pays an amount of money to test a product for a company bothers my ethical sensibilities. You are charging people to risk their health to help you make a profit (and hopefully to help others). Does the payment effect subject recruitment? After all, you might have the best potential subjects but if they don’t have the entry fee, then they don’t get to participate. Given that wealth is associated with educational background and race (because of structural and historical injustice in U.S. society), this approach to research means the subject pool will never be diverse.

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP) has issued recommendation for when pay-to-play studies might be considered: Does the study meet standards of scientific quality, is the risk-benefit ratio justified, why aren’t traditional funding sources being used, will paying interfere with the subject’s decision-making process, has an IND been filed with the FDA, and the cost of participation should never be more than the cost of the medication. In other words, the subjects’ payment should not ever be for profit. Andrews has said that the $1 million fee is just the cost of the medication. But in other interviews he has said that the cost is just a few hundred thousand. Which is true?

Ethics Dumping

While this trial does not seem to meet the recommendations, the trial is listed at ClincalTrials.gov—“a database of privately and publicly funded clinical studies conducted around the world”. However, that can be deceiving since entries into that database are not subject to editorial oversight. A warning on the website says, “The safety and scientific validity of this study is the responsibility of the study sponsor and investigators. Listing a study does not mean it has been evaluated by the U.S. Federal Government”. In effect, being in the database can be a marketing bullet point. One way to assure that one is beyond the regulatory gaze of the FDA, though, is to run the trial in another country. As mentioned above, this study is being conducted in a small clinic that lacks a history of running clinical trials, in the town of Zipaquirá, Colombia (about 45 minutes outside of Bogotá). This South American nation is actively recruiting companies to run clinical trials there, touting their “competitive costs”, “high enrollment rate” (taking subjects from its universal health care registry), being a “top destination for medical tourism”, “government tax incentives”, and “Fast and predictable national Ministry of Health regulatory pathway—about 30 days for medical devices)” according to bioaccess.com. Libella CEO Jeff Mathis says they chose Colombia because it offered the “path of least resistance”.

Ethics dumping is the practice of taking research studies that would be difficult if not impossible to conduct in a high-income country (due to regulations, IRB review, oversight) and bringing them to a middle- or low-income country. The advantage for the research is lower cost, a ready pool of subjects who can be paid less, universal health care systems (someone else pays for any problems), and being out of the limelight. However, usually the devices and medications being tested, if effective, would be unaffordable to the local populace. Thus, people living in poverty are often taking all of the risks without any way of receiving future benefits. In this case, it is likely not the easy pool of research subjects, but rather the anonymity afforded and the lack of regulatory red tape.

Some might argue that with IRBs, FDA regulations and other laws, research has just become too hard and too expensive to conduct in the United States, thus the move offshore. They would probably suggest we consider lowering our regulatory and ethical requirements to spur drug development. After all, Libella and its founders stand to make unimaginable sums of money if their approach proves effective. While cutting regulations might make business sense, from a research, medical, and ethical standpoint, sacrificing the protection of human subjects and the health of the greater population is more important than speed or profit.

Take Home

Even if we could de-age people, should we? If the cost is $1 million to extend a lifespan, then the process won’t be available to everyone. This is a eugenic choice where the preferred character trait is wealth. The rich and famous could become a long-lived subspecies of homo sapiens. Most people, though, will continue to age and get wrinkles and gray hair. In some countries, aging is viewed as good. Older people are seen as wise, and experienced, and are respected and honored. In the U.S., we think older isn’t productive and is a drain on society. If the wealthy are suddenly not growing old, it might increase stigmatization against the vast majority of people (i.e. the non-rich) who will continue leading normal lives. It may lead to more significant discrimination toward people who look old.

That same million dollars could provide a lot of preventive care. Some of our most expensive vaccines cost $60 per dose (per the CDC). $1 million buys over 16,666 doses. Other vaccines are 1/3 of the price and would save three times as many lives. That money could provide education, nutrition, and shelter for many people and those are all things that we already know improve health and extend lifespan. Today, in the United States, average life expectancy is decreasing. Rather than looking for the Fountain of Youth for a few, we should put our resources into giving more people the opportunity to reach old age.

1 Although a good story, this tale is just a story. In reality, Ponce was the governor of Puerto Rico who was forced out of his position. There are no records from Ponce’s life that mention the Fountain of Youth.

2 Interestingly, the trial is listed at ClinicaTrials.gov as only recruiting 5 participants, but Andrews has said publicly he is recruiting 15.